Contents tagged with Ocean_liners

-

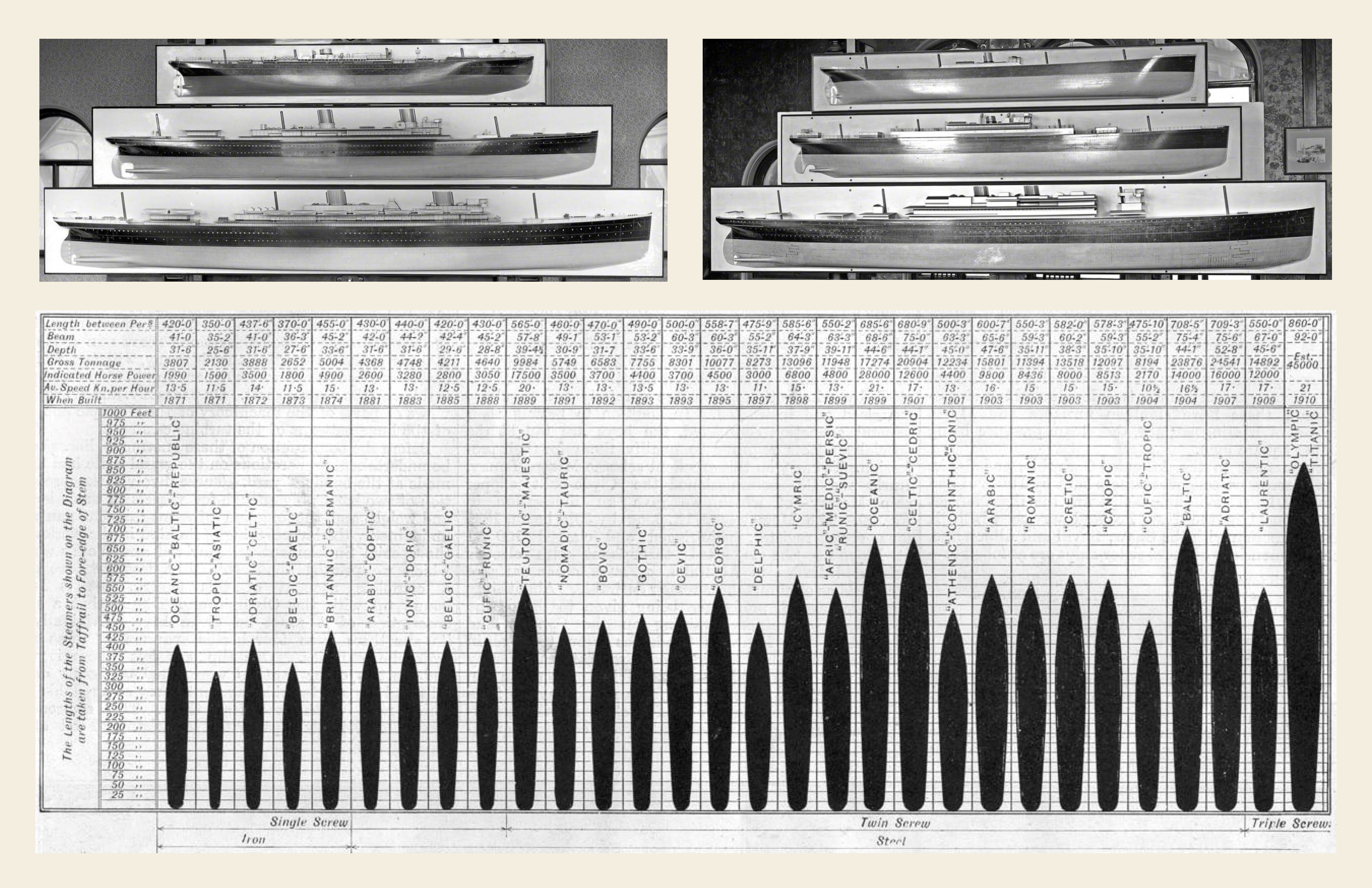

The development of oceangoing steamships 1840-1940

In 1936, on the occasion of the inauguration of the British passenger liner R.M.S. QUEEN MARY, the British cigarette manufacturer, the Churchman's published a series of 50 cigarette cards on which the new liner was advertised under the title "Wonders of the QUEEN MARY". On one of the cards, the newest ship of the owner shipping company, Cunard Line, built in 1936, was compared with the company's very first ship, BRITANNIA, put into service almost a hundred years earlier, in 1840.

Blank cards - cardboard sheets - were originally used to stiffen cigarette packets. Colored, stylish cigarette cards and match labels varied with pictures, witty texts, and informative descriptions began to spread as label art for marketing purposes after the appearance of cheap cigarettes available to the general public in the 1880s, and then, from the 1920s, the explosion the printing industry went through a similar development, and the new technologies of lithography and the expansion of consumer needs enabled the strong growth of the market.

That's when the thematic sets depicting celebrities (military leaders, movie stars, radio celebrities, athletes), sports (football, cricket, golf), nature (animal world, geography), history (castles, coats of arms, battle scenes), or even technical achievements (airplanes, cars, locomotives, naval- and merchant ships) appeared on cigarette cards for the design and production of which the largest tobacco product manufacturers employed separate graphic groups - studios specializing in cigarette cards and match labels.and even published independent collector's catalogs, with which they all tried to ensure brand loyalty among new smokers for their products.

These products also attracted the attention of younger age groups who are thirsty for novelty, who, primarily through collecting, or after school disappointments, found the opportunity to learn while having fun through the interesting pictures and the explanations written on the back of the illustrated cards (while the tobacco companies gained potential consumers in the form of young collectors who learned smoking habits from adults). In the 1920s and 1930s, 100 British tobacco manufacturers launched 2,000 collectible series (!) in this way. Among them was the series of 50 cards, in which there is a representation comparing the size of QUEEN MARY and BRITANNIA.

From a genre point of view, such representations sold on cigarette cards form an independent type of comparison drawings presenting the impressive dimensions of ocean liners. The representation of the two famous Cunard ships inspired the president of our association, who works on the "Encyclopedia of Ocean Liners", to recreate the 1936 representation by using the scale profile drawings he made:

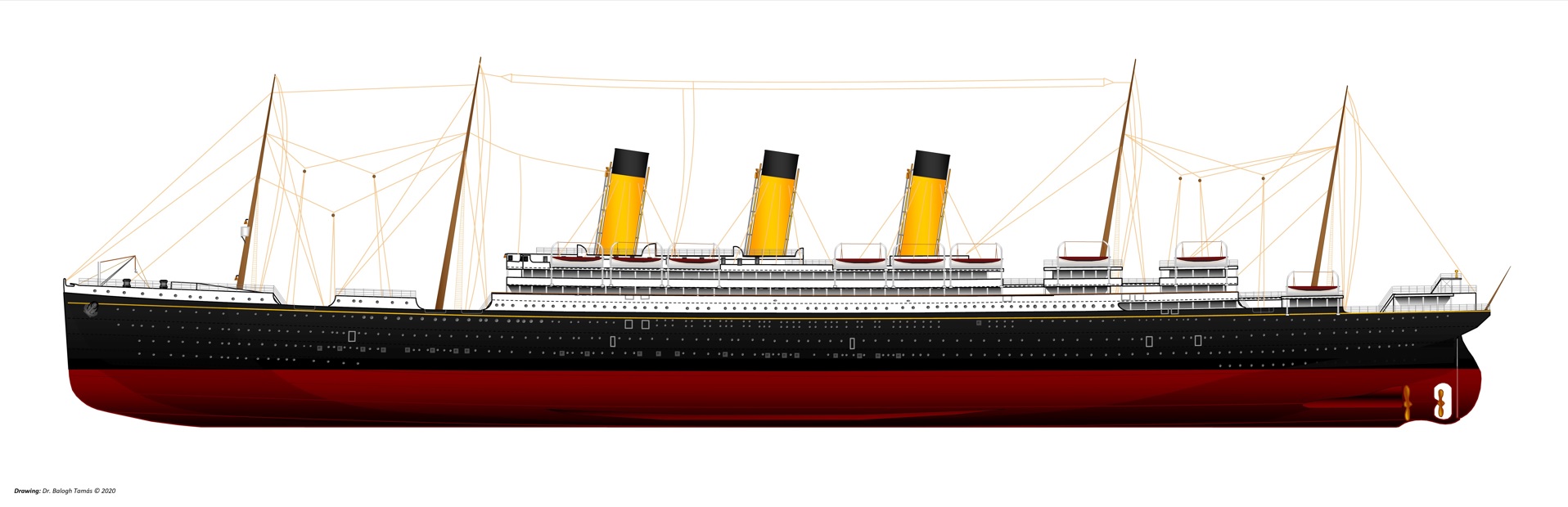

Figure 1: The recreated comparison drawing and the original from 1936 (in the upper right corner). Made by Dr. Tamás Balogh © 2025.

Steamship construction gained momentum in the middle of the 19th century, similarly to the construction of steam locomotives during the railway mania between 1830-1847 (when 263 laws and 15,300 km of new railways were established in Great Britain alone, although the mania had its effect throughout Europe, since 10,000 km of railways were built in Germany between 1845-1855, 2,341 km between 1847-1867, then 21,200 km in Hungary.

The steamship - thanks to the work of Robert Fulton, who perfected it - was nevertheless initially more popular in America than in Europe: In 1829, the United States had 54,037 tons, Great Britain barely 25,000 tons. 10 years later, 193,423 vs. 82,716 tons, in 1848, 427,891 vs. 168,078 tons, after another ten years, and in 1858 already 729,390 vs. 488,415 tons was the ratio. There had to wait until 1876, until the year came when more steamships were built than sailing ships.

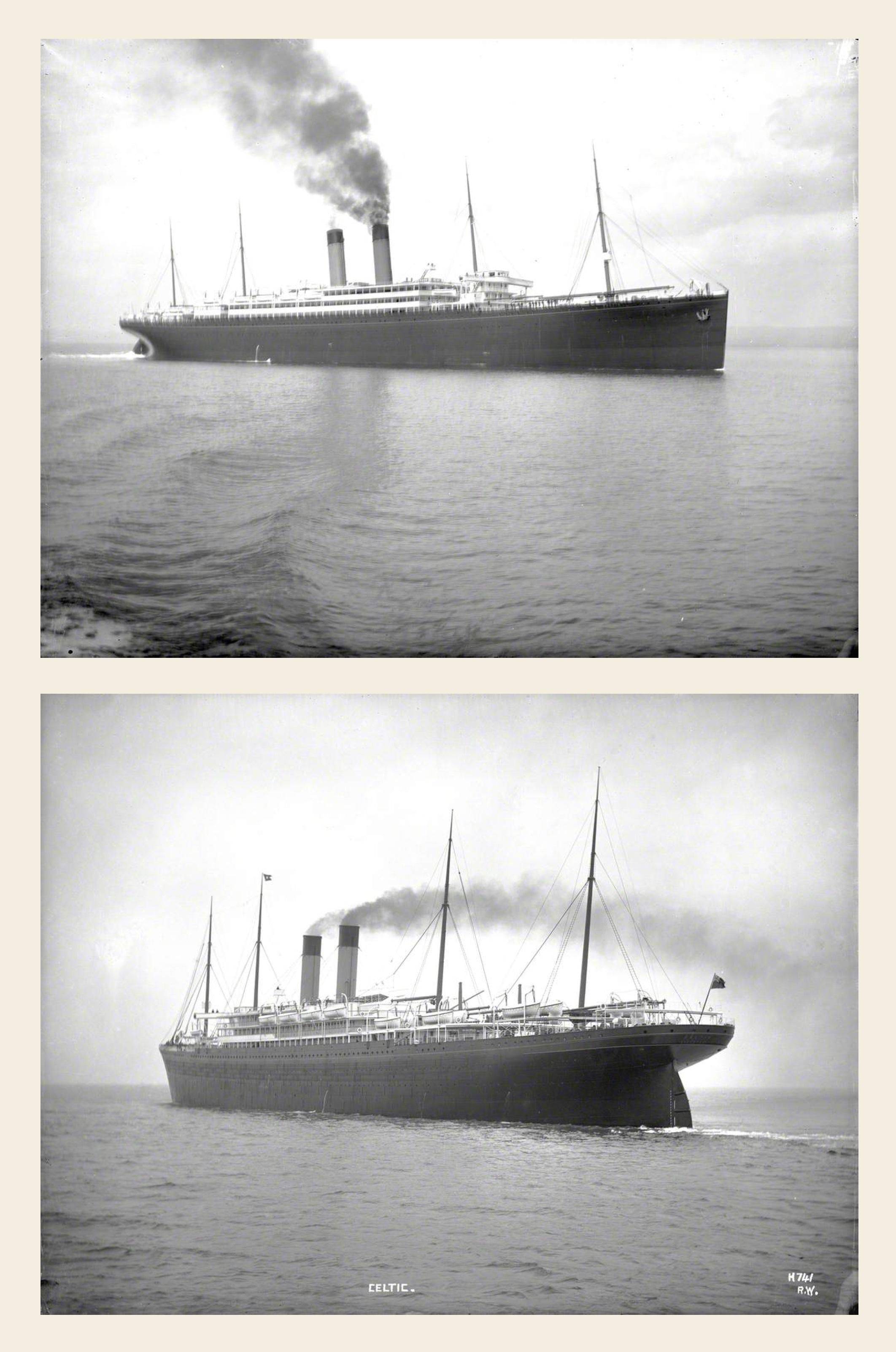

The rudimentary steamships of the 1830s, which were still mostly only for stunts - barely a few tens of meters long, no more than 200-250 tons, and equipped with steam engines of barely 50 HP - grew rapidly, and their performance improved considerably due to the development of their structure and steam engines. The milestones of the development is marked by such technical feats as the ships depicted in the picture above: The wooden BRITANNIA was a large ship in its time, with a length of 63 meters and a width of 10.3 meters. In addition to the sails of her three masts, she was propelled by paddle wheels powered by a 740 horsepower two-cylinder steam engine. The ship's 4 coal-burning boilers provided the ship with a speed of 8.5 knots (16 km/h) with a daily coal consumption of 38 tons, which could go even faster in case of favorable winds and currents. The ship had a volume of 1,154 tons and was able to carry 115 passengers with a crew of 82. She crossed the Atlantic between Liverpool and Halifax in 12 days and 10 hours. In comparison, the QUEEN MARY is built of steel, has 310.7 meters in length, while her width is 36 m. Her four propellers were driven by the same number of steam turbines with an output of 700,000 horsepower. The ship's 27 oilburner boilers powered the ocean liner at a speed of 28.5-32.8 knots (53-61 km/h) using 1,000 tons of fuel oil per day. For 14 months between 1936-1937, and then without interruption between 1938-1952, she held the Blue Ribbon for the fastest Atlantic crossing. The gross tonnage of the ship is 81,237 tons, the number of passengers that can be taken on board is 2,140, while the number of crew is 1,100. Her fastest crossing time was 3 days 22 hours 42 minutes on the Halifax-Southampton route.

Between 1837-2003 - that is, while ocean liners were being built - several significant periods followed each other In the hundred years between 1840 and 1940, considered the heroic age of ocean liners, 1,019 ocean liners were built worldwide, while the world's 16 largest seafaring nations in 1914 had a total of 8,445 commercial ships (cargo and passenger ships combined) of more than 1,600 tons (suitable for ocean crossings) and 14,282 less than 1,600 tons - that is, a total of 22,727 - in operation, a total of 42,416. 000 tons of space. From the Belle Époque, which is considered the golden age of ocean liners, to the present day (during the 111 years between 1912-2023) - excluding the war years - a scant 20 ocean liners have sunk. In comparison, 50 ocean liners were sunk between 1914-1918 and 144 between 1939-1945 as a result of acts of war (compared to a total of 5,000 ships sunk in World War I and a total of 20,000 ships sunk in World War II), while barely a dozen ocean liners served in both world wars.Ocean liners therefore represent barely 1 thousandth (0.0071%) of the nearly 3,000,000 known shipwrecks sunk in world history.

It would be great if you like the article and pictures shared. If you are interested in the works of the author, you can find more information about the author and his work on the Encyclopedia of Ocean Liners Fb-page.

If you would like to share the pictures, please do so by always mentioning the artist's name in a credit in your posts. Thank You!

Sources:

Hurd, Archibald: A Merchant Fleet at War, London, Toronto, New York, Melbourne, 1920.

Charles, Roland W.: Troopships of Word War II., Washington, 1947.

Kudyshin, Ivan; Chelyadinov, Mikhail: Лайнеры на войне. 1936 1968 гг. постройки, Moscow, 2002.

Tebutt, Melanie: Children and hobbies in 1930s Britain: cigarette cards

Smith, Eugene W.: Transatlantic Passenger Ships - Past and Present, Boston, 1947.

Sz.n.: Mercantile Fleets - British an Foreign, in.: Scientific American Reference Book, 1914. p.195.

-

RMS QUEEN MARY turned 90 years old

On September 26, 2024 90 years ago, the mighty oceanliner QUEEN MARY - built to the order of the Cunard Line - was launched in Clydebank, Scotland, at the John Brown Shipyard.

We commemorate the anniversary with a tableau presenting the history of the ship in our exhibition "Oceanliners".

During the period between the two world wars, most nations were at a shortage of the great ocean liners. On the one hand, an extremely large number of ships were lost in the unrestricted submartine warfare, and on the other hand, due to the post-war shortage of raw materials and capital, as well as poor working conditions in shipyards, their replacement progressed much more slowly than in that pre-war period, which had promised uninterrupted development of the transatlantic traffic. In 1914, the world's 16 largest shipping nations had a total of 8,445 ships larger than 1,600 tons (suitable for ocean crossings) and 14,282 ships smaller than 1,600 tons - that is, a total of 22,727 ships - in operation, with a total of 42,416,000 tons. Of the 16 countries, 9 participated as belligerents, and only 7 remained neutral in the First World War, in which 375 German submarines sank a total of 7,671 ships with a displacement of 15,716,651 tons. This is about a 40% (37%) loss. The situation slowly began to change only in the second half of the 1920s:

1926-1928.: Sir Percy Bates, chairman of the British Cunard Line, raises the idea of building 2 new larger and faster ships to replace the company’s 3 obsolete ocean liners - MAURETANIA, AQUITANIA and BERENGERIA.

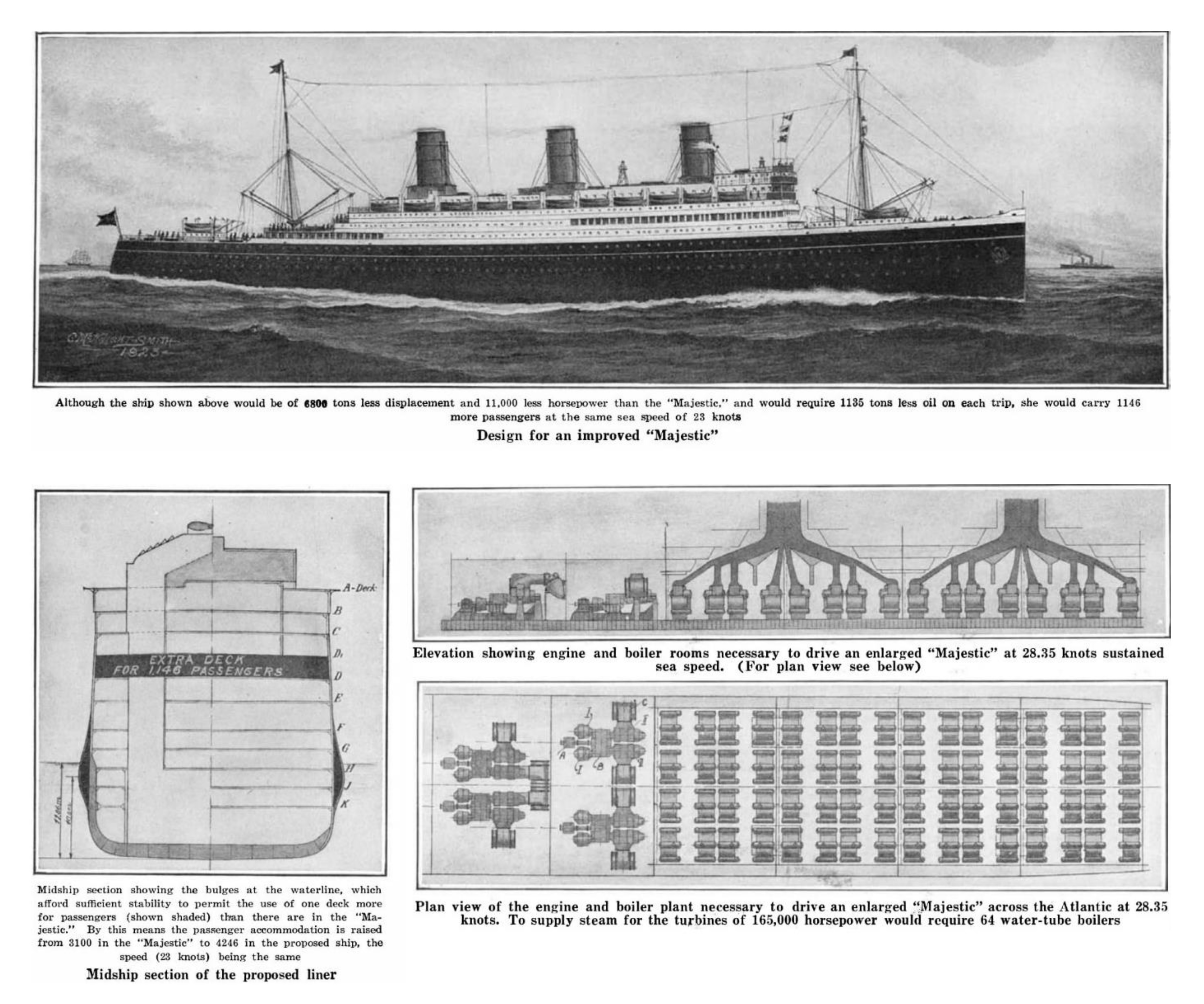

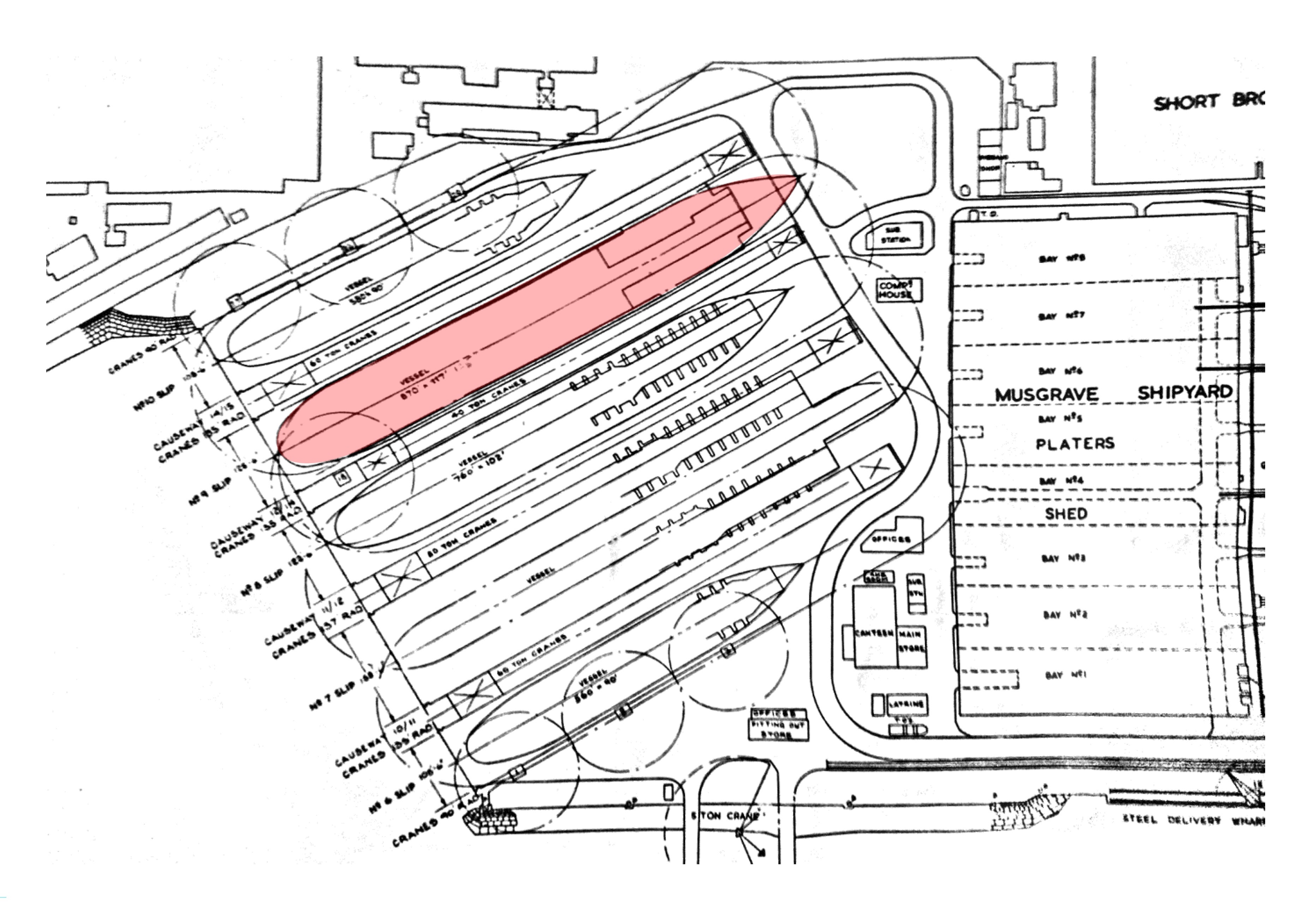

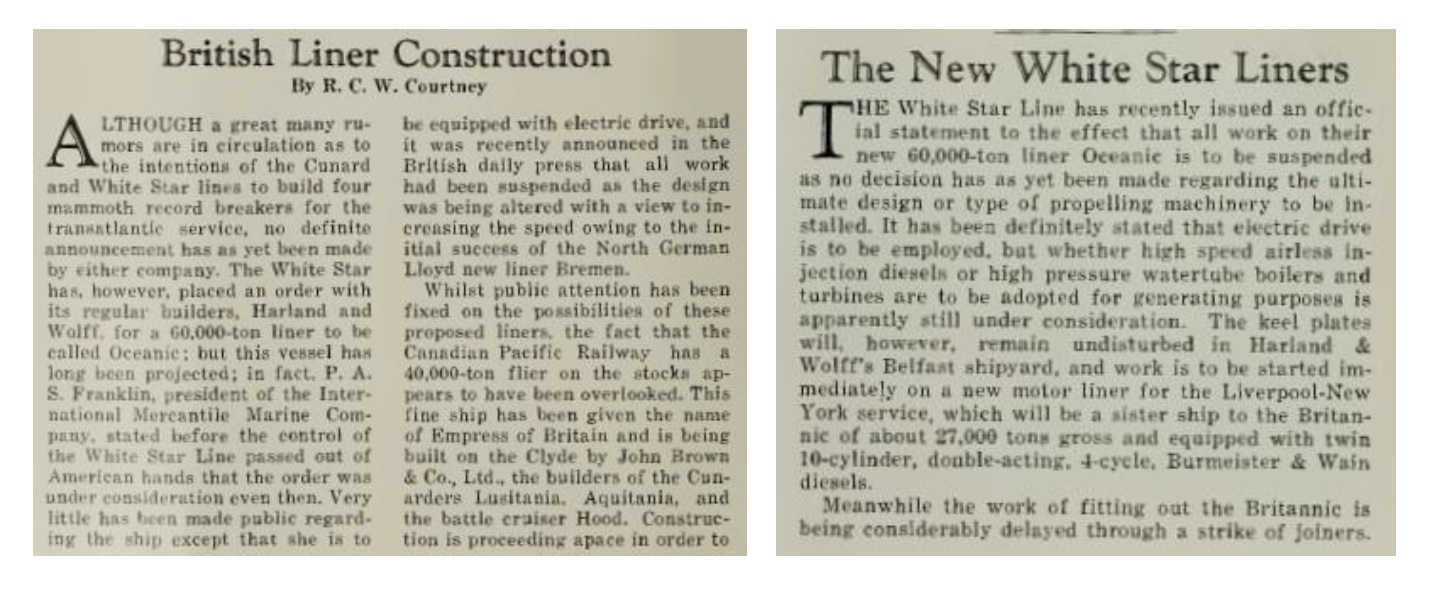

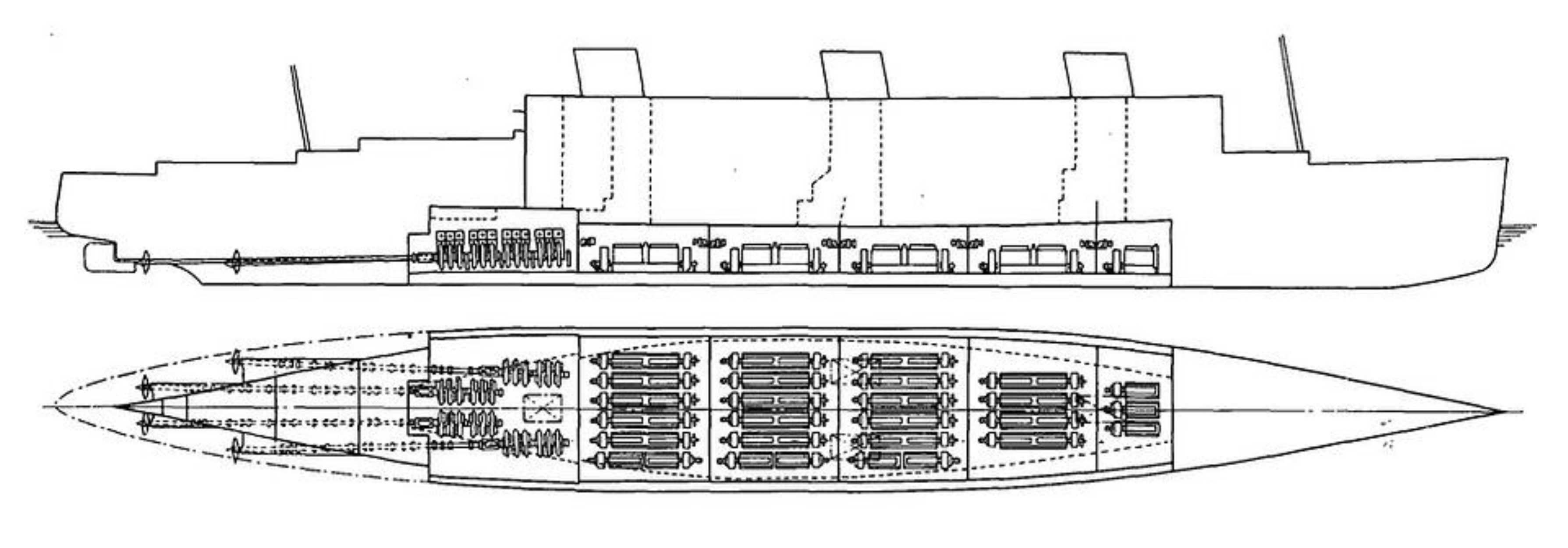

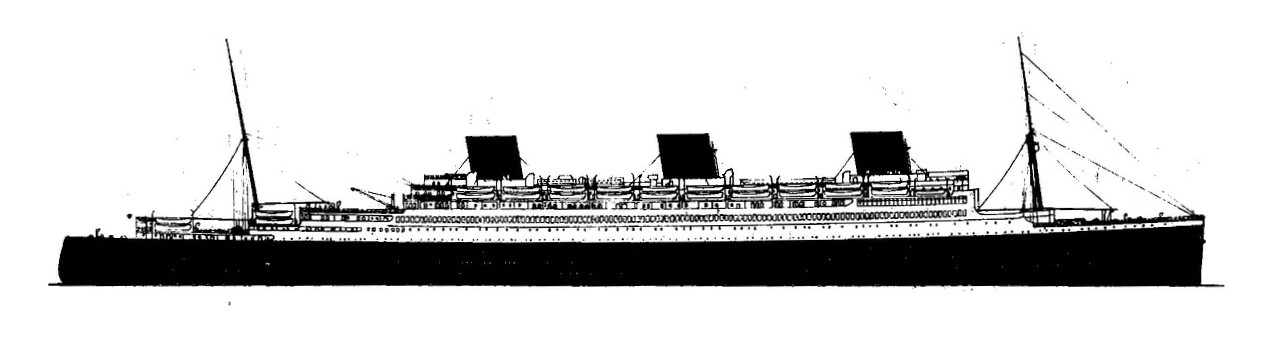

During this period, rival shipping companies will also enter with new ships into the North Atlantic rivalry. ROMA (1926) and AUGUSTUS (1928) are built in Italy. The pair of modern turbine steamers of Germany, the BREMEN and the EUROPA (1928) enters in service - BREMEN also breaks MAURETANIA's 20-year speed record, immediately on her first voyage. In France, the ILE de FRANCE (1926) is completed and the design of NORMANDIE (1928) is started. The British competitor White Star Line is laying the keel of OCEANIC III. (1928), which was planned to be the first ocean liner to exceed 300 m in length. In light of this international development, the design of the two new Cunarders capable of maintaining a weekly express service in the North Atlantic begins.

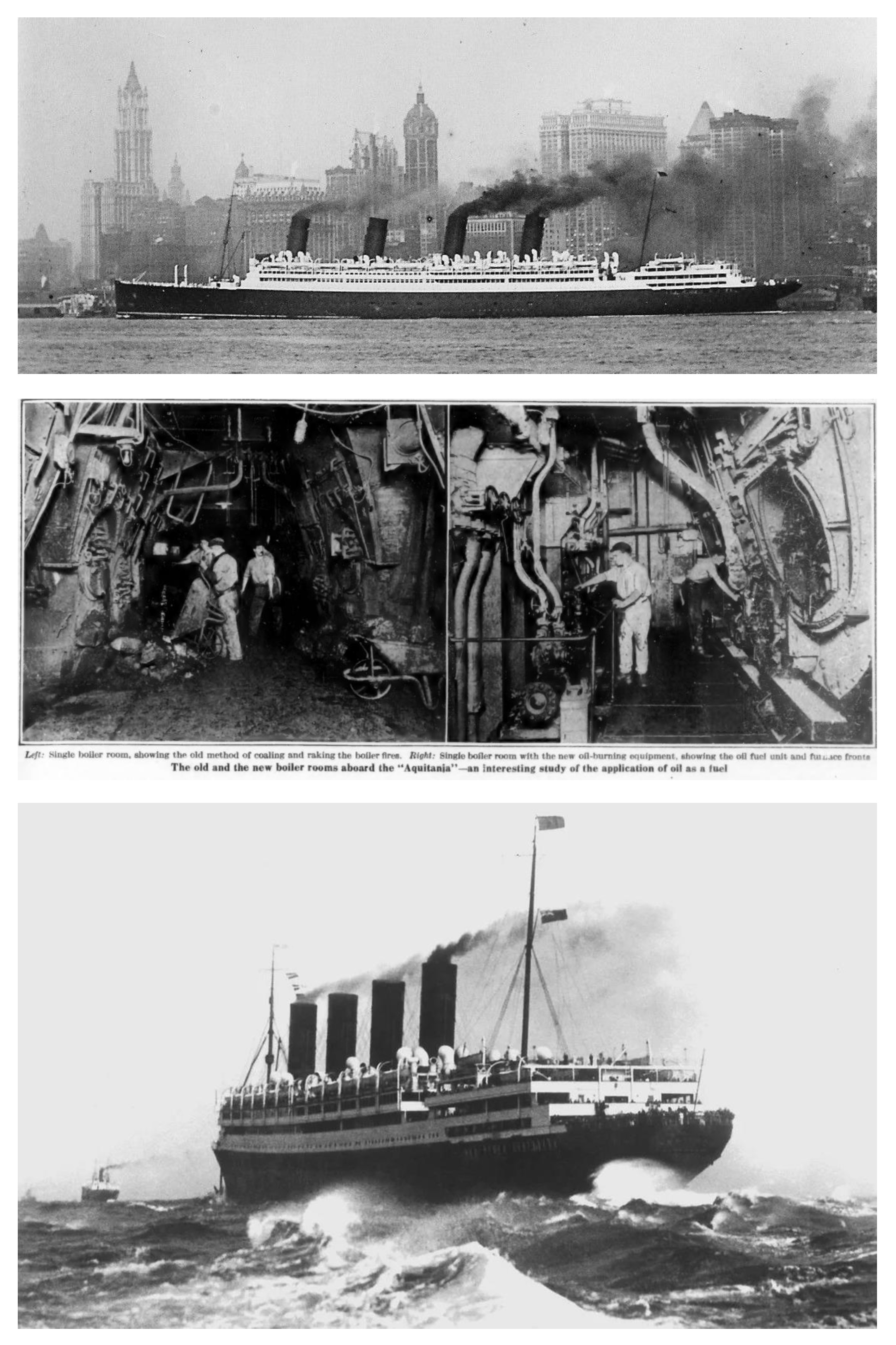

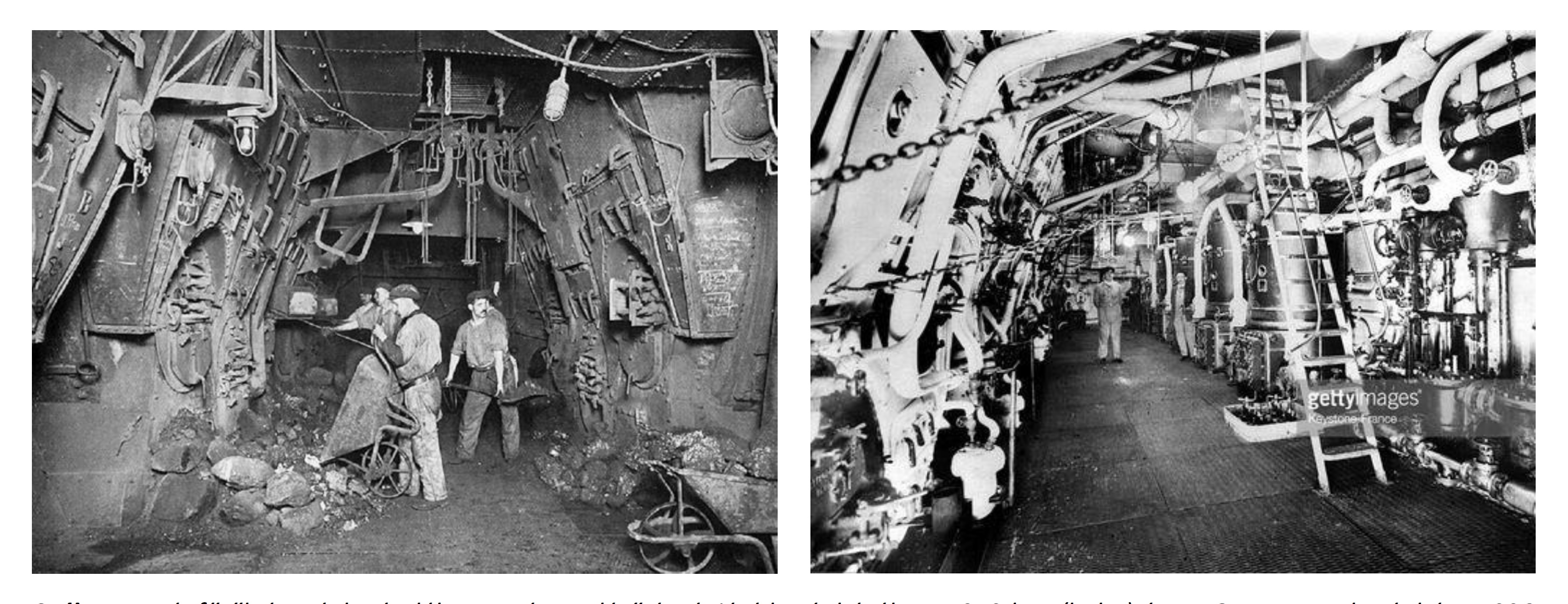

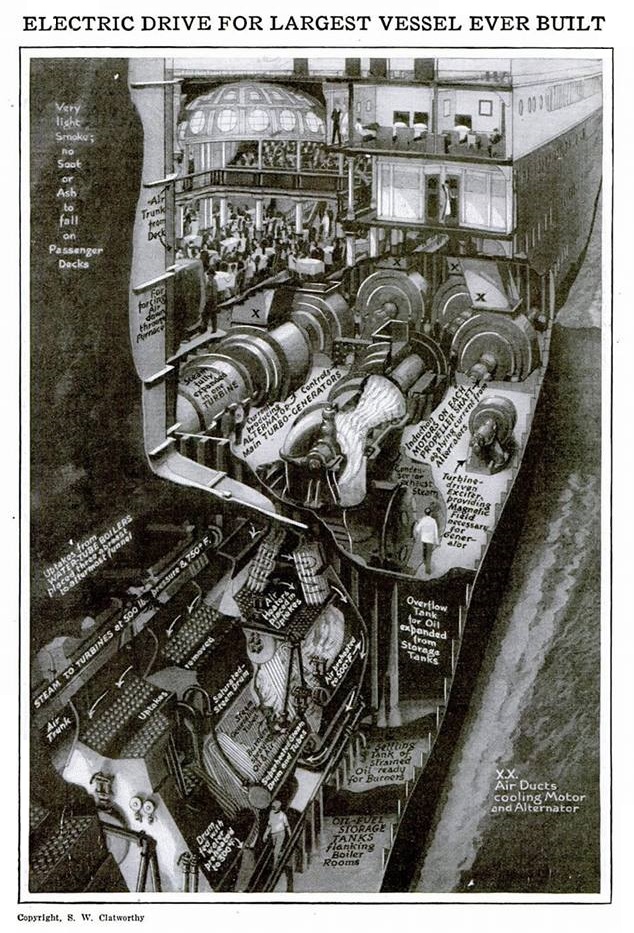

Size and speed are in the focus of the development (size increases comfort, as the larger the ship, the less it is affected by the elements, while the speed shortens the voyage). Switching to oil burning will reduce staying in ports to 18 hours (due to the shorter refuelling periode). Thus, by reducing the crossing time to 5 days, the work of the previous 3 ships can now be performed by 2. Cunard prescribed 112 hours of crossing time for new vessels (which required an average speed of 27.61-28.94 knots on different lengths of route used according to the season) and 11 months of continuous operation without repair and boiler cleaning, which required exceptional reliability.

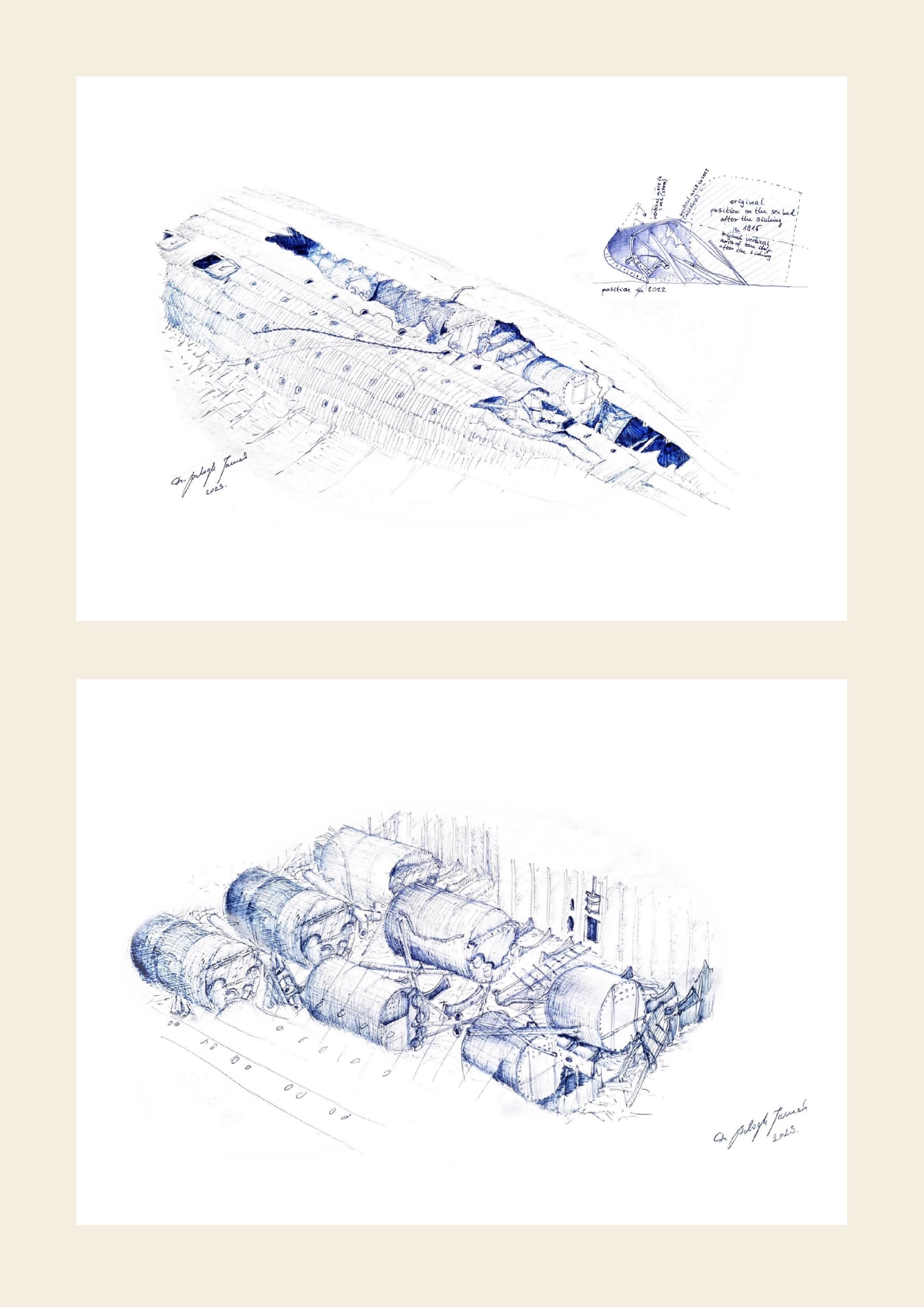

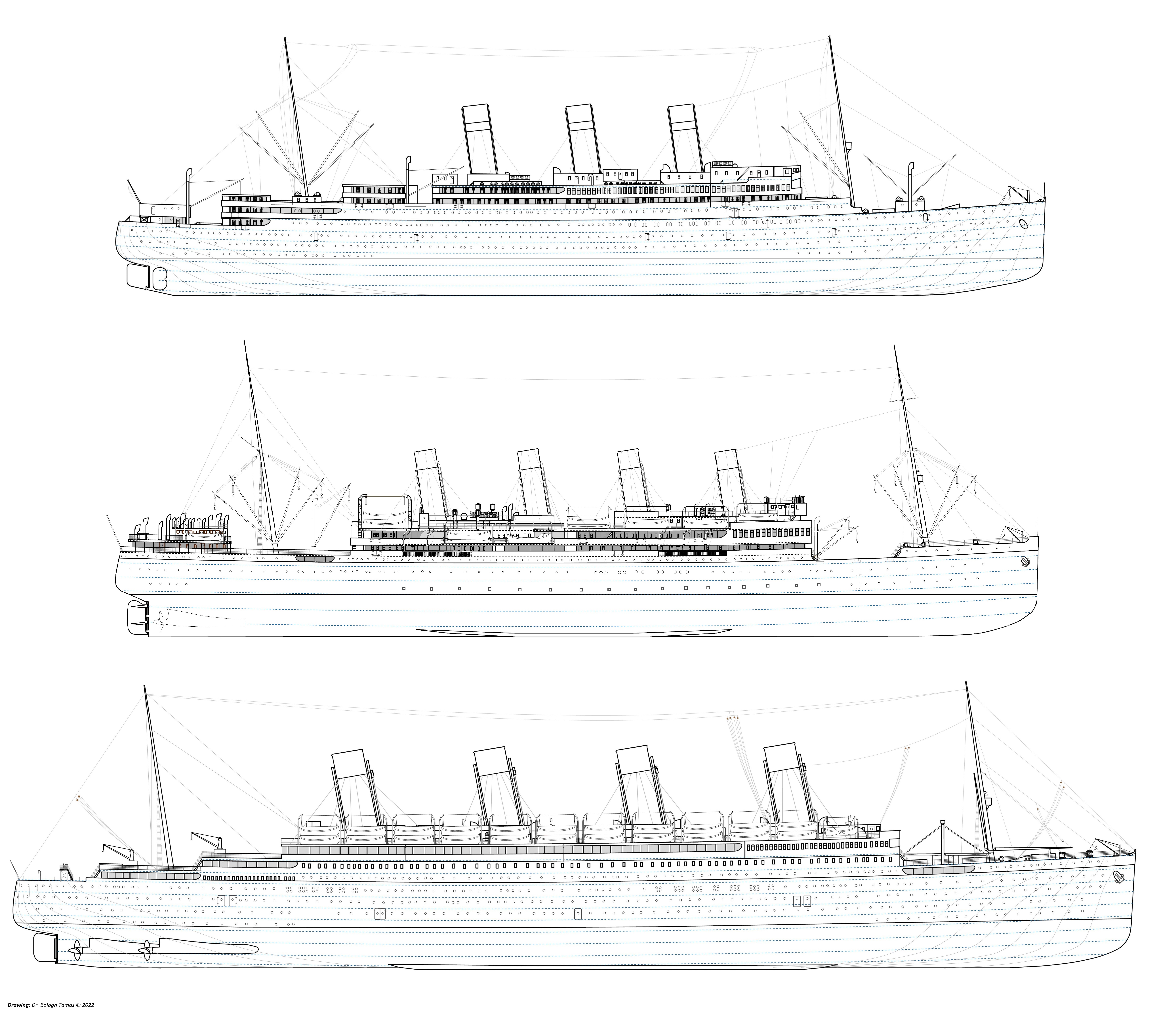

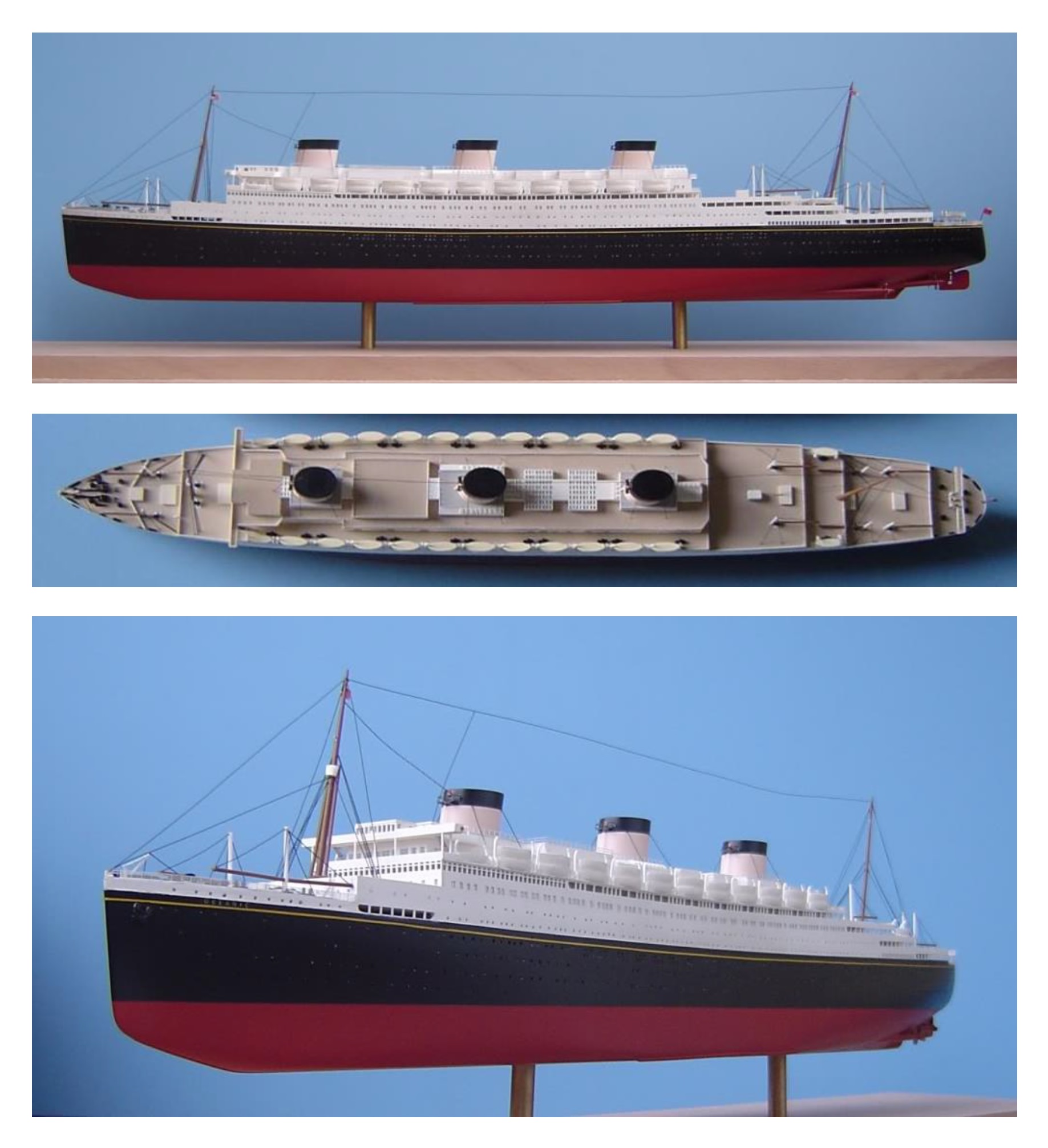

Fig. 1: The process of designing the QUEEN MARY: above, the first preliminary design of the then-unnamed ship - for the time being called "super AQUITANIA" - after the latest ocean liner of the Cunard company, from 1928. In the middle is the second preliminary design from 1930 (compared to the first, with a larger superstructure, cruiser stern, and glass-enclosed promenades). And below is the final design (with funnels of decreasing height towards the stern and on the "B" deck without the promenade still visible from the third funnel towards the stern in the previous designs).

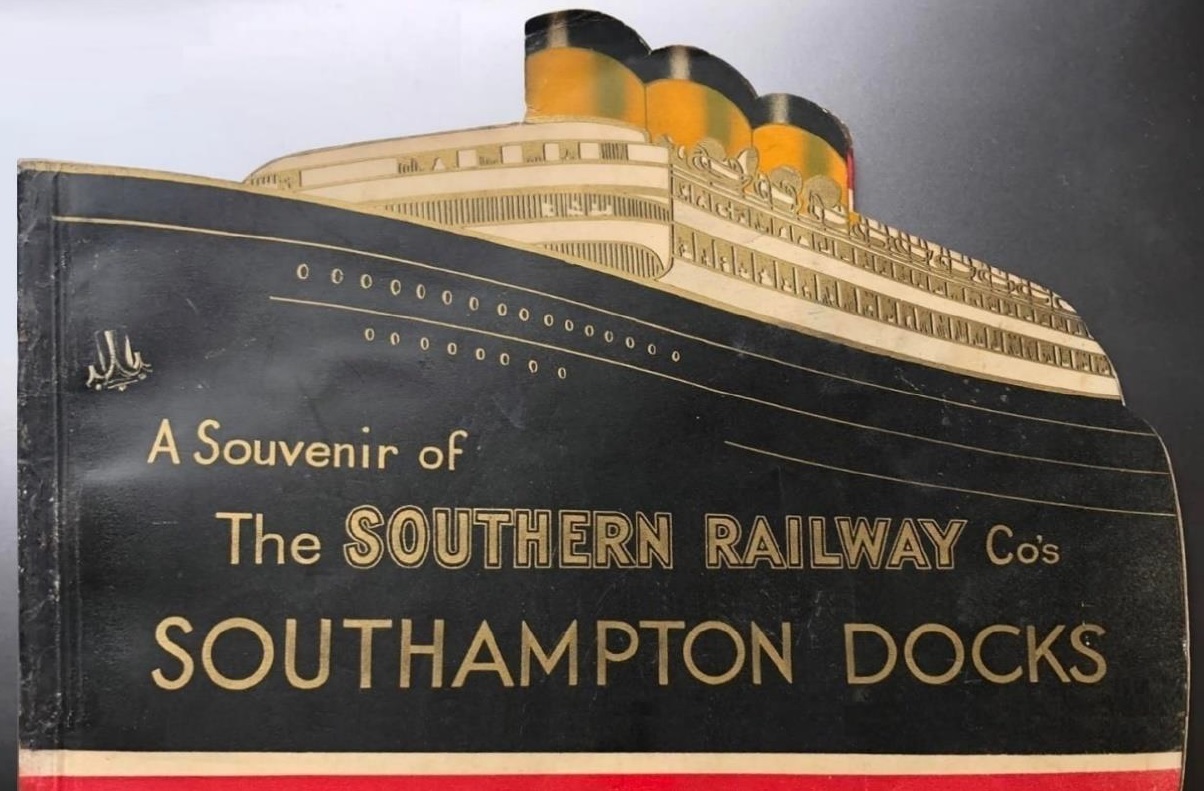

1930.05.28.: Ordering the first ship, the QUEEN MARY. Signalling to the Southern Railway Co. that construction of a new dry dock is necessary in Southampton (1,075 feet long, 124 feet wide and 40 feet deep) until 1933, for repair works of the two new vessels. According to the railway company, it is impossible to start construction of this size for another 8-10 years, and the construction of the planned dry dock will take 4-5 years. Sir Percy Bates replied, "No dry dock, no ship."

1931.01.01.: Agreement with the French and US authorities on the reception of new vessels. The French are offering Cherbourg, which has deeper waters and a larger port area, instead of Le Havre (this means a journey of 70 km and 30 minutes longer for passengers departing from Paris). Cunard leases a 1,000-foot-long pier from the New York Harbor Authority for £ 48,000 a year.

1931.12.11.: During the Great Depression, Cunard made a loss for the first time in many years. Construction of QUEEN MARY is suspended. The UK government is offering a loan to Cunard on the condition that it merges with the White Star Line, as the government says it is not desirable if two major UK shipping companies challenging each other in the North Atlantic trade, while there is a growing international competition.

1933.07.26.: Opening of the KING GEORGE V dry dock in Southampton. Final dimensions of the dock: 1,200-foot-long, 135-foot-wide, 48-foot-deep . 180,000 tons of water from the dock can be drained in 4 hours.

1934.03.07.: Cunard and White Star Line will sell vessels of their Atlantic fleets to the new Cunard-White Star Line shipping company. In return for the merger, the UK government will provide £ 3 million to complete QUEEN MARY and £ 5 million to build QUEEN ELIZABETH, in addition to providing an additional £ 1.5 million in working capital to the new company.

1934.09.26.: Launch of the R.M.S. QUEEN MARY.

Fig. 2.: The QUEEN MARY tableau of our traveling exhibition "Oceanliners". (archive images: Péter Könczöl, text and graphic design by Dr. Tamás Balogh).The future of the ocean liner has become uncertain several times since her withdrawal from active service. In 1970, with the involvement of the French marine explorer Jacques Ives Cousteau, they originally tried to create a spectacular museum presenting the wildlife of the deep sea on the site in her former boiler rooms from which all the boilers were dismantled, but the idea failed within two years due to the mass death of the fish introduced in the aquariums (however, it caused irreparable damage to the ship's power plant). Between 2006 and 2009, the condition of the underwater parts of the hull caused concern. And most recently - between 2016 and 2023 - the general neglect of the ship, which suffered from many changes of operators and a lack of sufficiently thought business concept, put the giant - which represents cultural heritage with outstanding universal value for the mankind - in danger. In 2016, the cost of the most necessary interventions to prevent the occurrence of an irreversibly declining state was estimated at 300 million dollars. Until 2018, 23 million dollars were spent primarily on fire protection works. In 2022, among the ship's 22 lifeboats (15 original and 7 from other ships), 11 lifeboats (4 original and 7 from other ships) deemed to be in the worst and most dangerous condition were destroyed due to non-governmental organizations planned to be involved in the preservation of the heritage could not fulfill the strict artefact management conditions prescribed by the owner municipality. At the same time, almost another 4 million dollars were spent on the renovation of the ship's plumbing and railing system, the repair of the original interior floor coverings (linoleum and carpets), and the improvement of the comfort equipment of the passenger spaces (WiFi, etc.). The ship, which reopened on April 1, 2023, has since generated a net profit of $3.5 million, which will hopefully be reinvested into the continued preservation of the ship, thus avoiding the sad end waiting for the s.s. UNITED STATES, which is the last Mohican of transatlantic passenger traffic.

We are confident that the QUEEN MARY will continue to satisfy the curiosity of those interested in the golden age of transoceanic passenger transport in a dignified condition for a long time to come and will continue to present visitors on board with unique experiences.

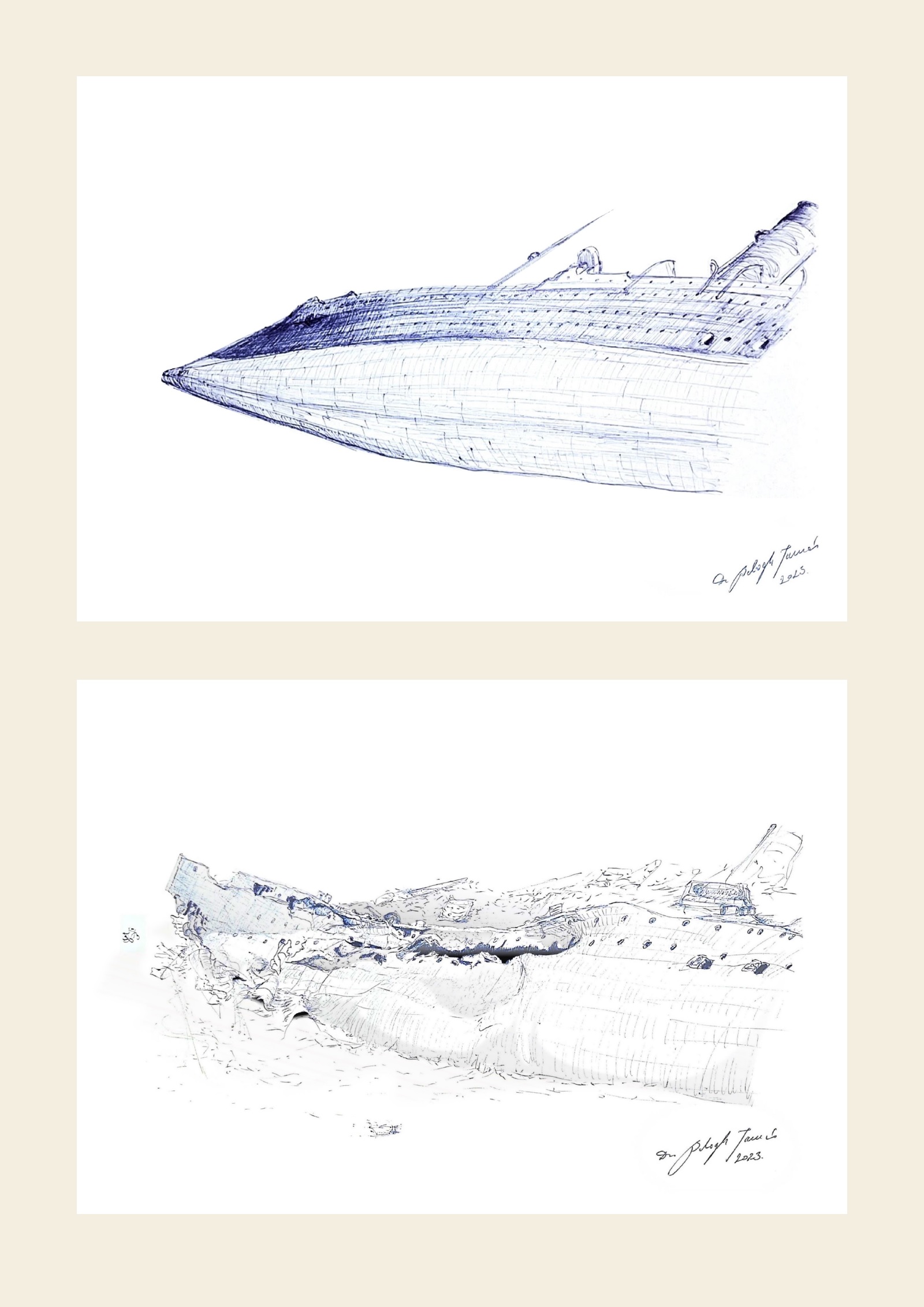

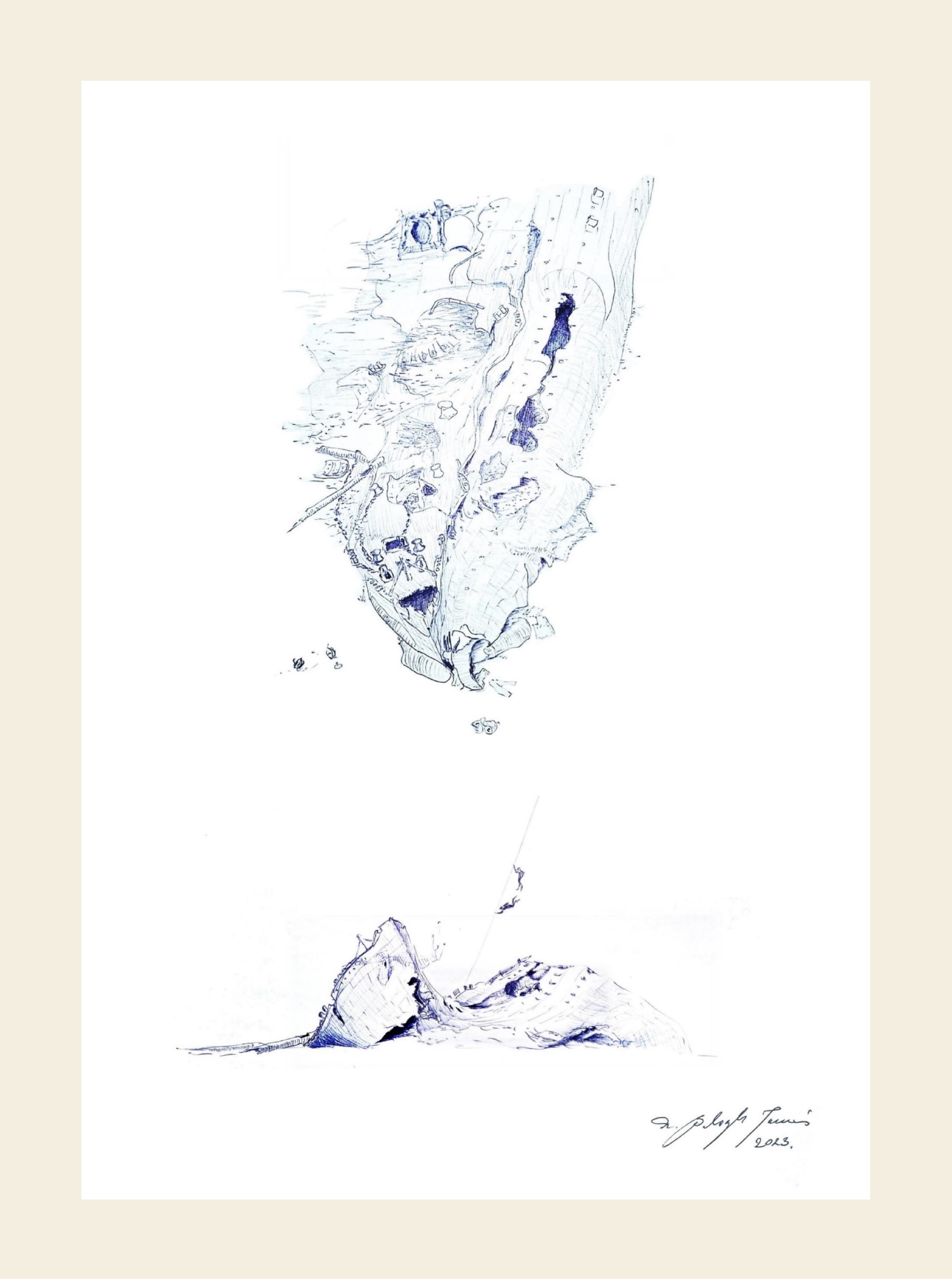

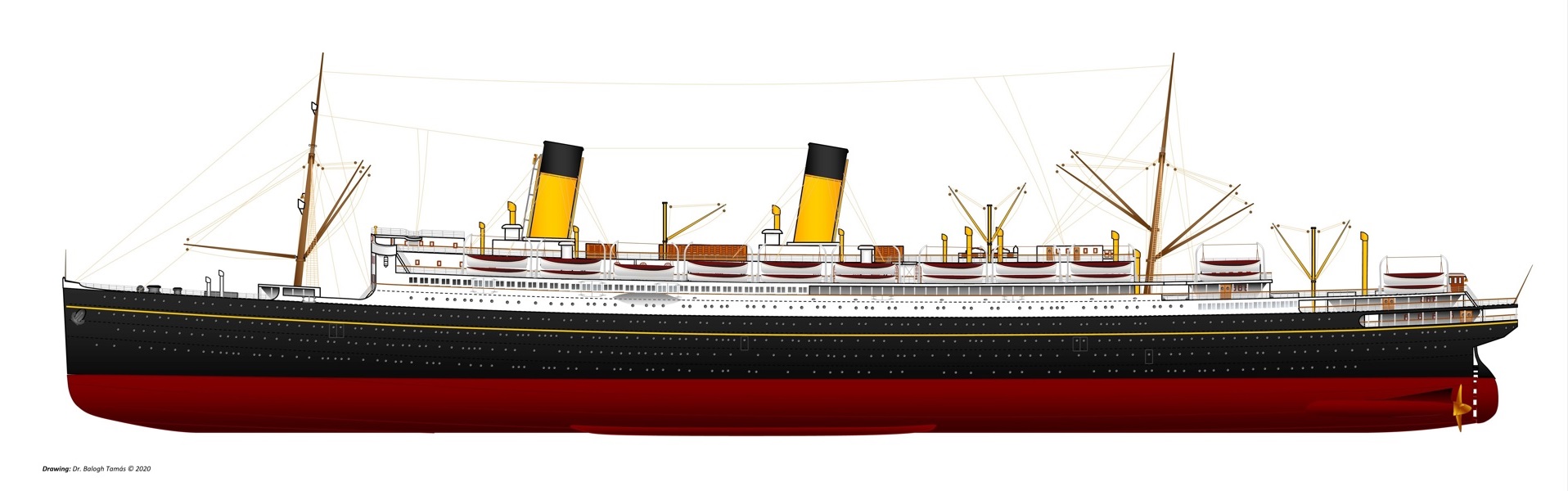

Fig. 3.: Profile of the RMS QUEEN MARY. (drawing: Dr. Tamás Balogh).This profile is part of next book of Dr. Tamás Balogh, the "Liners - great pictorial encyclopedia of giant steamships" featuring the history of ocean-going passenger steamers from 1838 to 2003. More info - synopsis, some sample pages, an interview and a report - here.It would be great if you like the article and pictures shared. If you are interested in the works of the author, you can find more information about the author and his work on the Encyclopedia of Ocean Liners Fb-page.

If you would like to share the pictures, please do so by always mentioning the artist's name in a credit in your posts. Thank You!

-

The beginnings of airmail from land to sea

On August 14, 2024, one of the greatest moments of civil aviation took place 105 years ago: the first time a mail sent from land was delivered to the deck of a ship navigating on the high seas by aircraft. With this experiment, a decade-long process has come to an end, and it has been proven that combined air-sea mail delivery by plane is possible. In my latest article, I recall the details of the successful experiment and the series of events that started the process leading up to it.

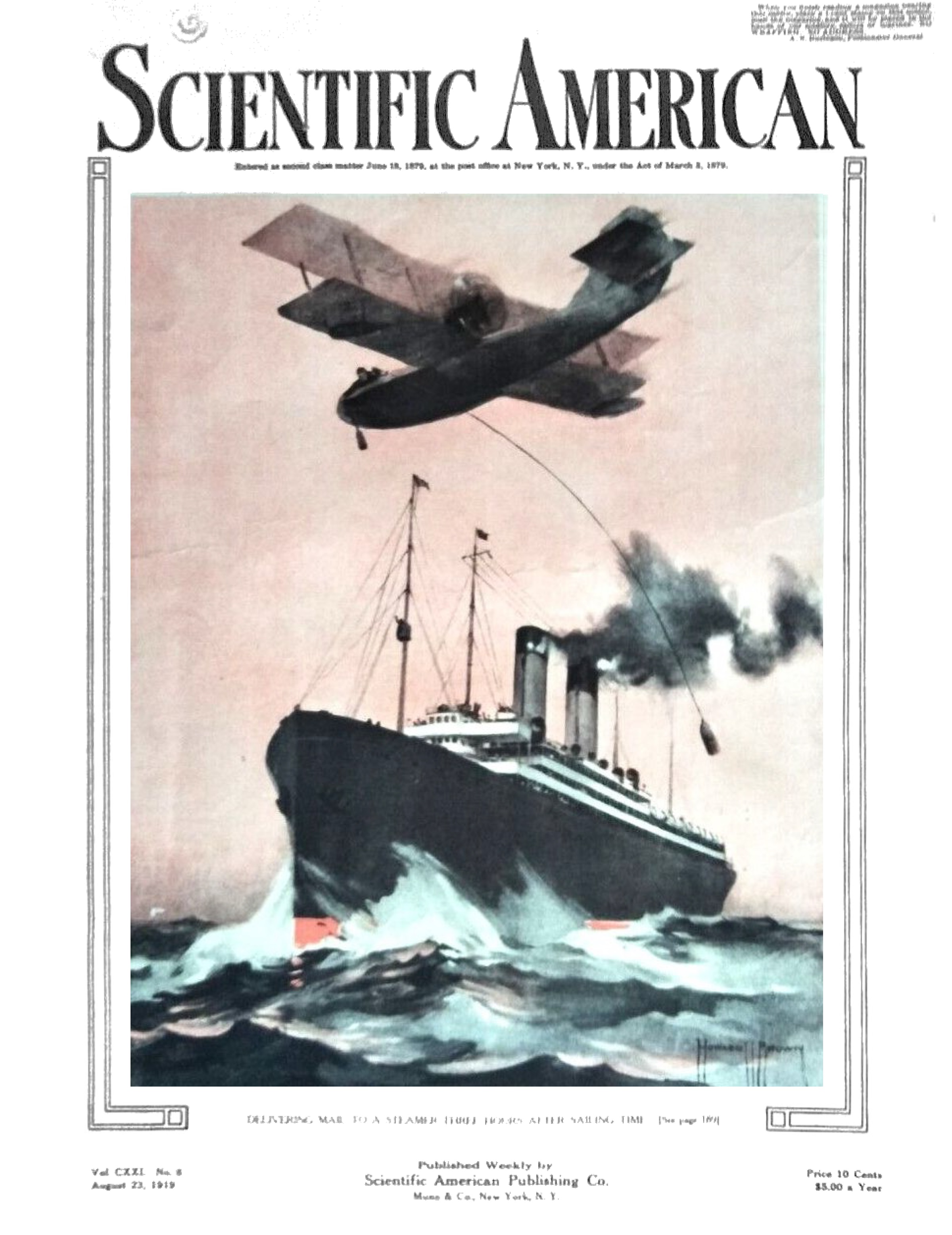

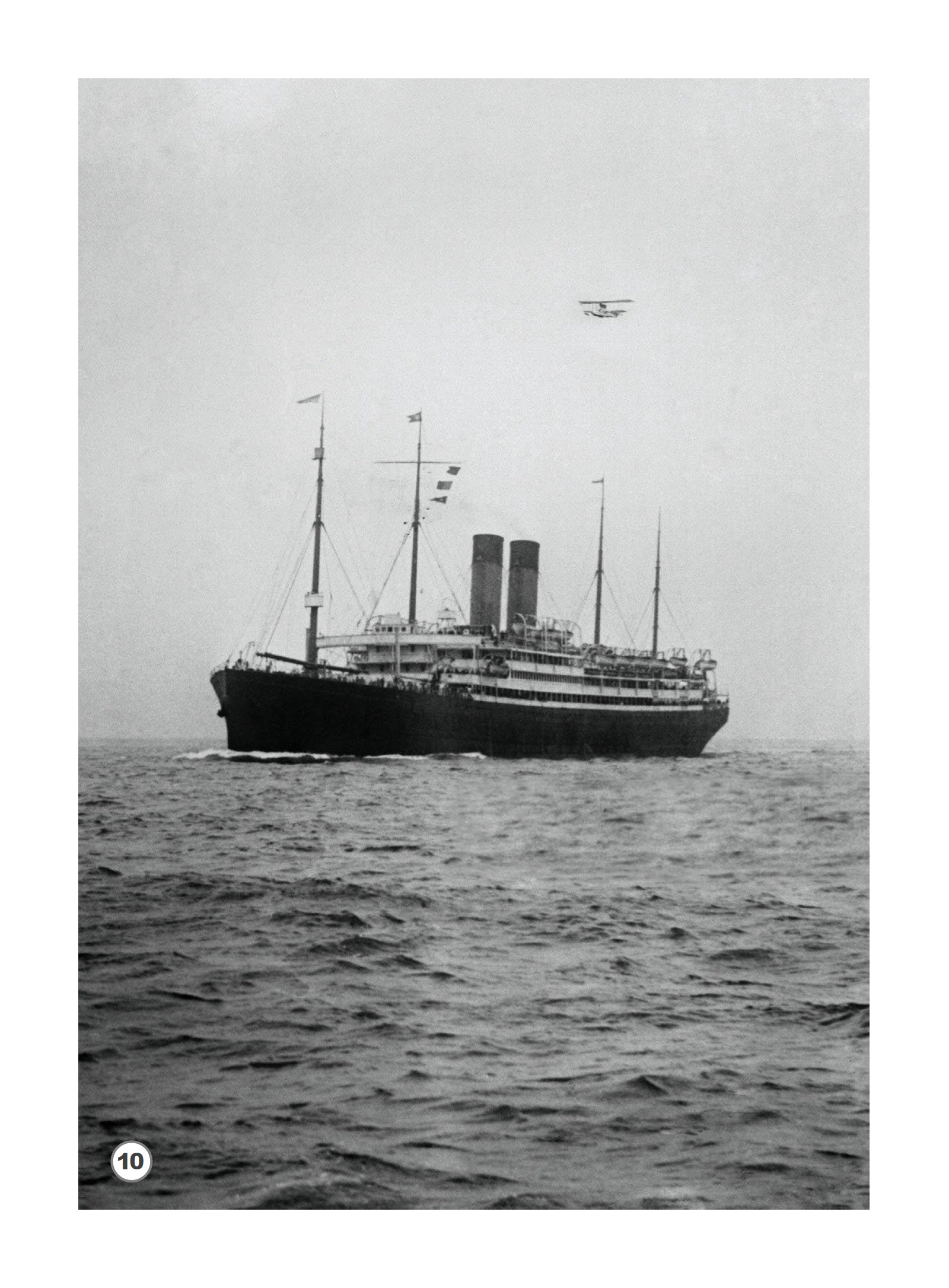

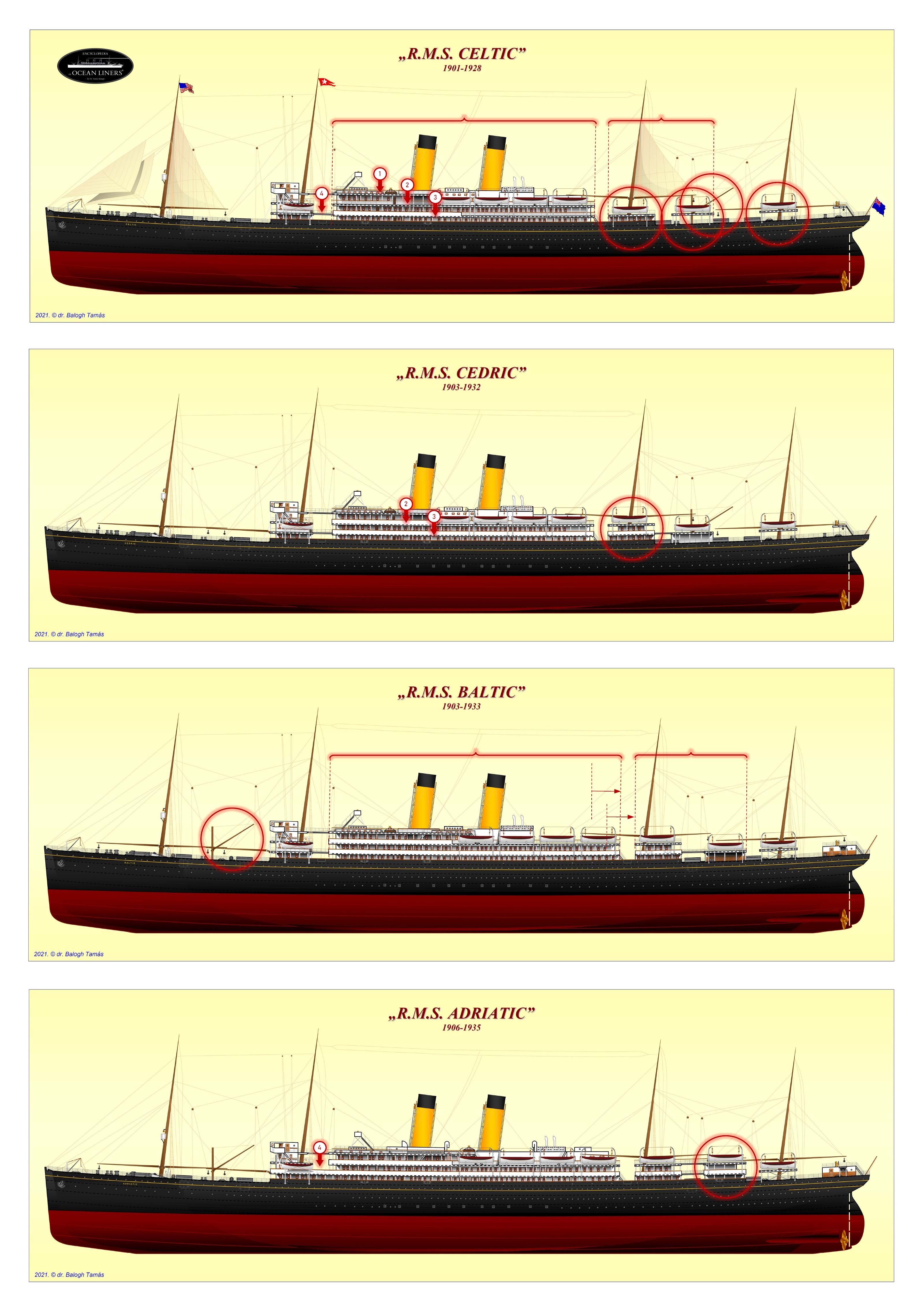

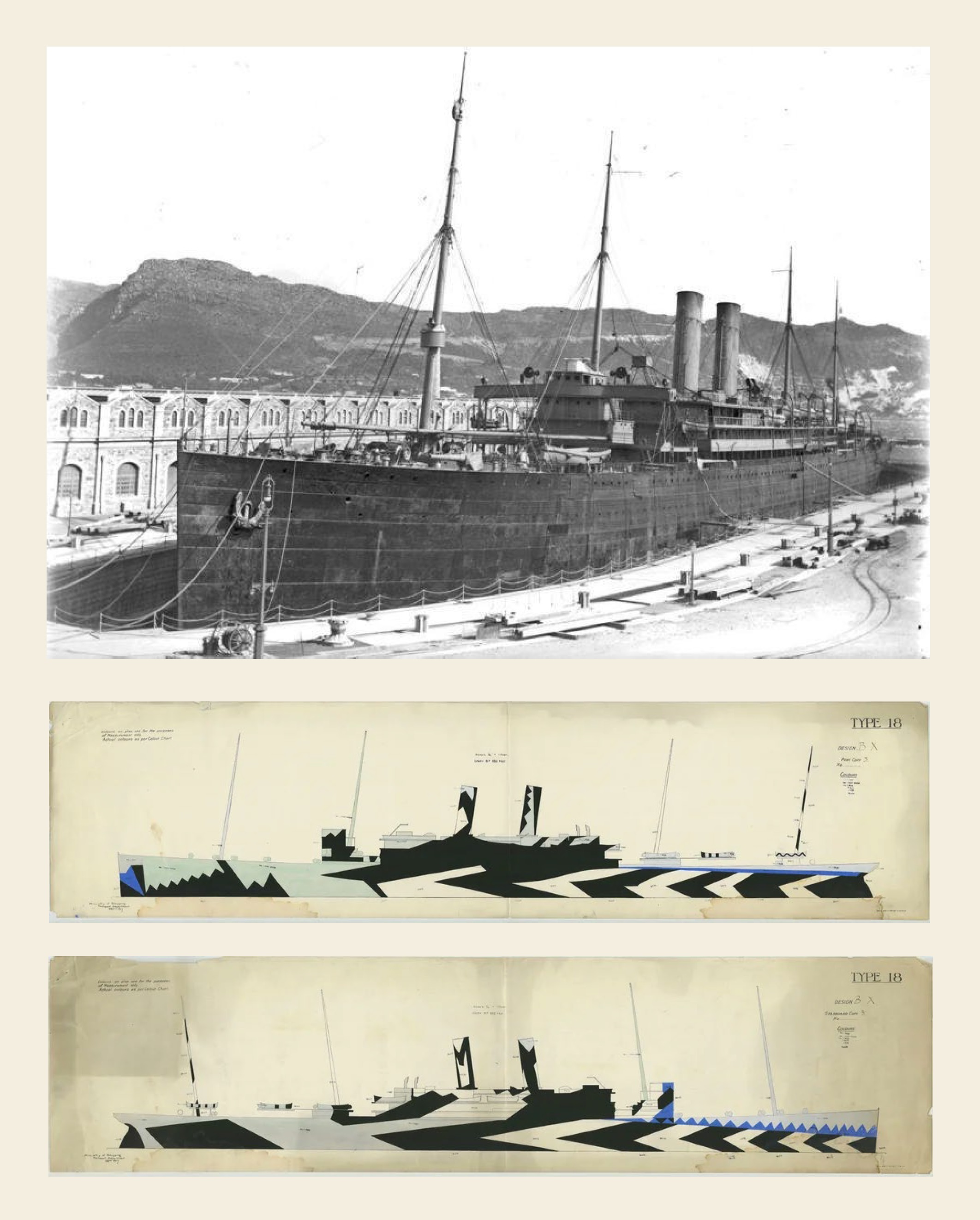

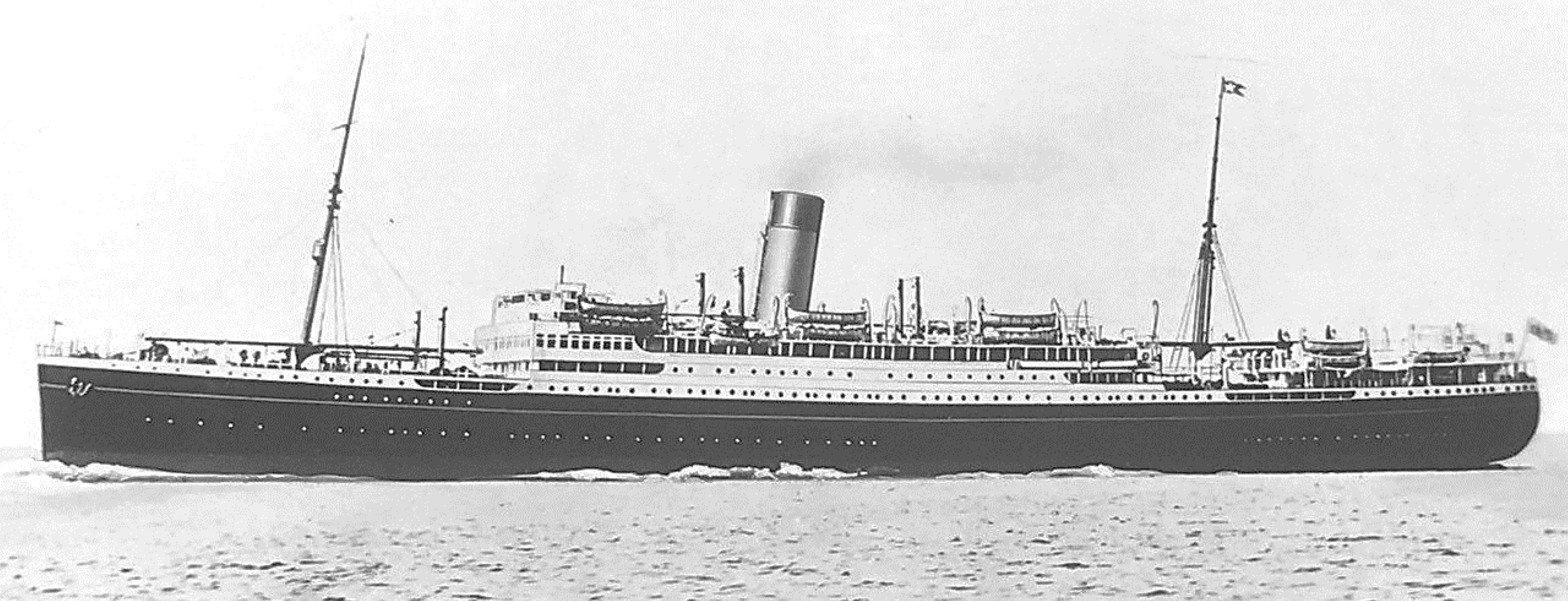

Fig. 1: White Star Line's ocean liner R.M.S. ADRIATIC - member of the famous "Big Four" - contributed to the first successful implementation of air-sea mail delivery. Depiction of the successful experiment carried out on August 14, 1919 on the front page of the "Scientific American" magazine (source).

Preface:

The American Wright brothers - small engine and bicycle mechanic Orville and Wilbur (both enthusiastic gliders, followers of the German Otto Lilienthal) - performed their first test flight on December 14, 1903, the 121st anniversary of Montgolfier's first hot air balloon flight and then three days later the first sustained flight with their heavier-than-air, guided aircraft, which they had been working on for years to develop. However, they managed to make the first full circle - 1.2 km long - only one year later, on December 20, 1904, with their perfected airplane. The American public was moderately enthusiastic about the invention, but the French Alero Club (which had been actively experimenting with the implementation of machine-powered aeronautics for some time) recognized the significance of the invention. In its own country, the airplane only gained more publicity in the context of the Hudson-Fulton Celebration held between September 25 and October 9, 1909, when a spectacular demonstration was organized for the various modes of transportation, and within this framework - as the latest achievement of steam navigation technology - the the British ocean liner LUSITANIA was also exhibited at the ceremony, which also included the public flight of Wilbur Wright, who gained world fame with his demonstration flights in Europe at the end of 1908 and the spring of 1909. As part of the celebrations, a demonstration flight from Governor's Island to the grave of General Ulysses S. Grant and back took place on September 29 and October 4. About one million New Yorkers were able to see the 33-minute flights and the LUSITANIA, although probably only a few of them suspected that they were witnessing the meeting of the past and the future, as fragile airplanes completely supplanted the celebrated mammoth ocean liners just 60 years later from transcontinental passenger transport. But until then, the two modes of transport existed side by side, and between the two world wars, their unique cooperation was also realized in the form of air-sea mail deliveries from land to ships and back.

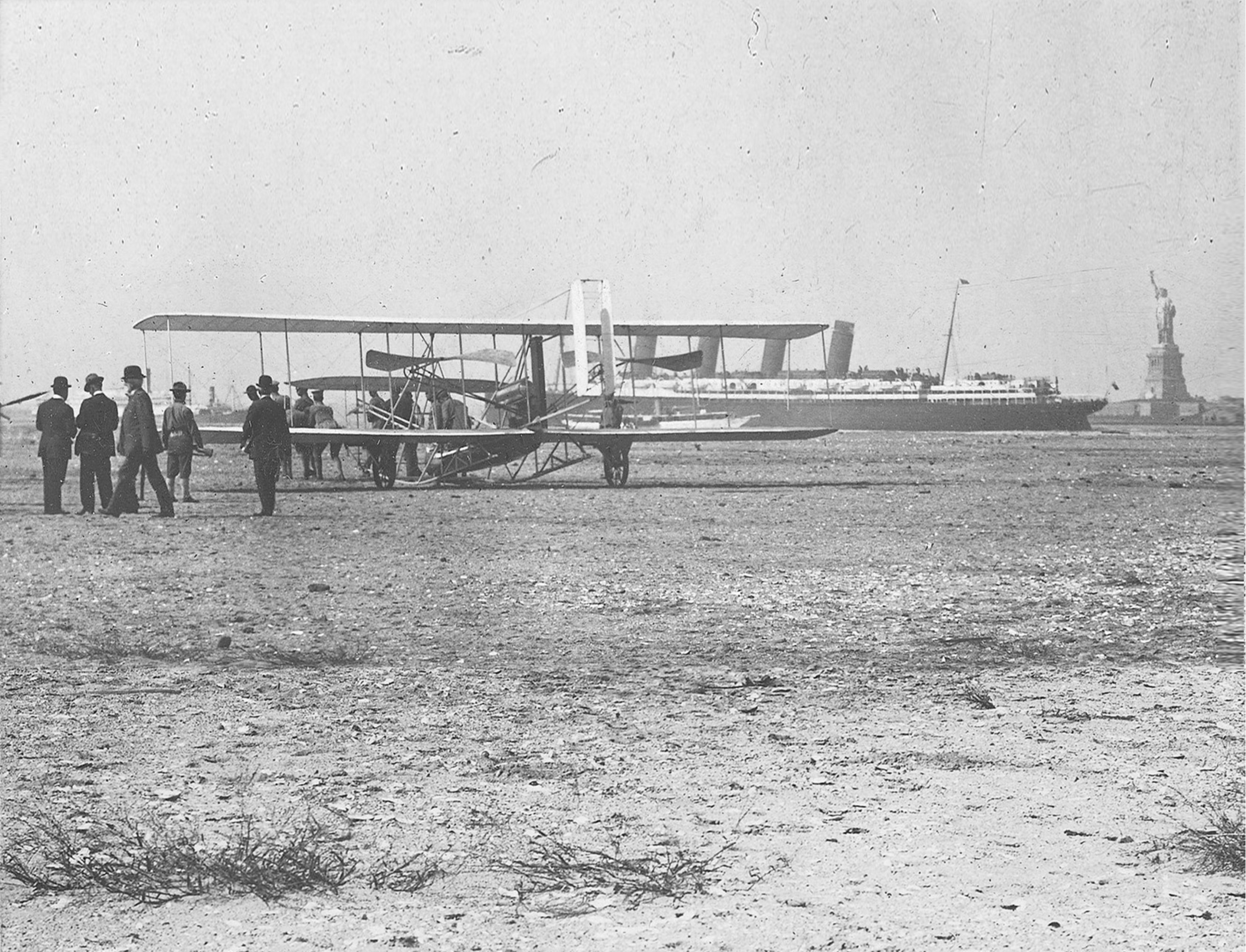

Fig. 2: Pilot Wilbur Wright and mechanic Charlie Taylor prepare to fly around the Statue of Liberty using the Wright "A" Flyer (the Wright brothers' fourth aircraft design) using Governor's Island Airport on September 29, 1909. In the background, the mighty LUSITANIA, speed record-holder of the oceans. (Source)Introduction:

The beginnings of civil aviation can be traced back not only to the invention of aircraft before the First World War, but also to their develpoment during the war (i.e. for the spread of more and more reliable monoplanes, made of light metal - aluminum -, equipped with increasingly powerful engines, replacing older biplanes made of wood and canvas), and to the insatiable passion for flying of the trained pilots who survived the war. The experienced fighter pilots, who were left without a job due to the disarmament after the end of war, were happy to demonstrate their skills in public in order to earn money after their dismissal from the service, and at the same time indulge their passion. Many American pilots became members of various flying circuses (so-called "barnstorming"), which flew across the country in small and large cities, holding spectacular shows and entertaining paying passengers. The individual initiatives eventually turned into organized, group shows, and big airshows started all over the country, with air competitions, acrobatic stunts and imitation of aerial combat scenes (which also inspired Hollywood when filming movies about the First World War). In fact, the practice of today's Red Bull Air Race also has its roots in flying circuses. And one more thing: the continuous development. The aerial acrobats of the flying circuses also competed with each other for first place (who was more successful, faster, etc.), so their operation stimulated the development of controls, engines and airframes. The Schneider Prize, which was founded in 1913 and promised a reward of 1,000 pounds, and similar prizes led to a series of increasingly faster and slimmer monoplane designs: the pilots competing for the various prizes encouraged progress. One element of this was the expansion of civilian use of aircraft. Although transcontinental flight was the desired goal, it proved to be unattainable for a long time. On the other hand, the first, still isolated, attempts at airmail delivery took place before and during the First World War, namely in the United States.

Attempts to implement regular air and the first air-sea mail delivery:

1) The very first - unofficial - attempt was made before the invention of airplanes, on August 17, 1859, when John Wise tried to deliver 100 letters in his airship from Lafayette, Indiana, to New York. However, the attempt failed after a short flight of 60 km due to the lack of suitable wind, and after the forced landing, the mail was finally delivered by rail.

2) Had to wait for a good fifty years until the next attempt: A federal bill authorizing the US Postmaster General to investigate the practical applicability of airplanes in mail delivery was presented by Texas Representative Morris Sheppard on June 14, 1910. The proposal was not accepted, and the New York Telegraph mocked it like this: "Love letters will be carried in a rose-pink aeroplane, steered by Cupid’s wings and operated by perfumed gasoline. … [and] postmen will wear wired coat tails and on their feet will be wings."

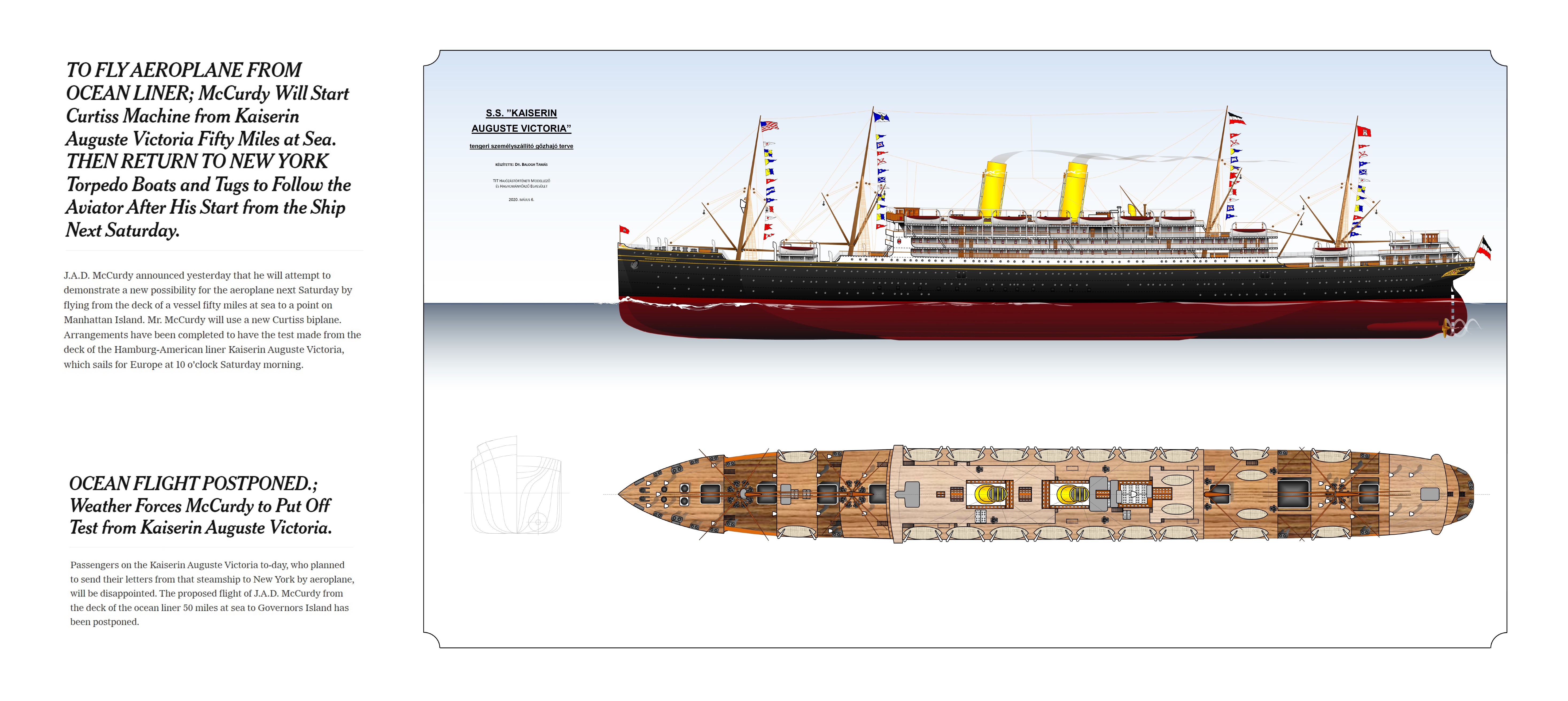

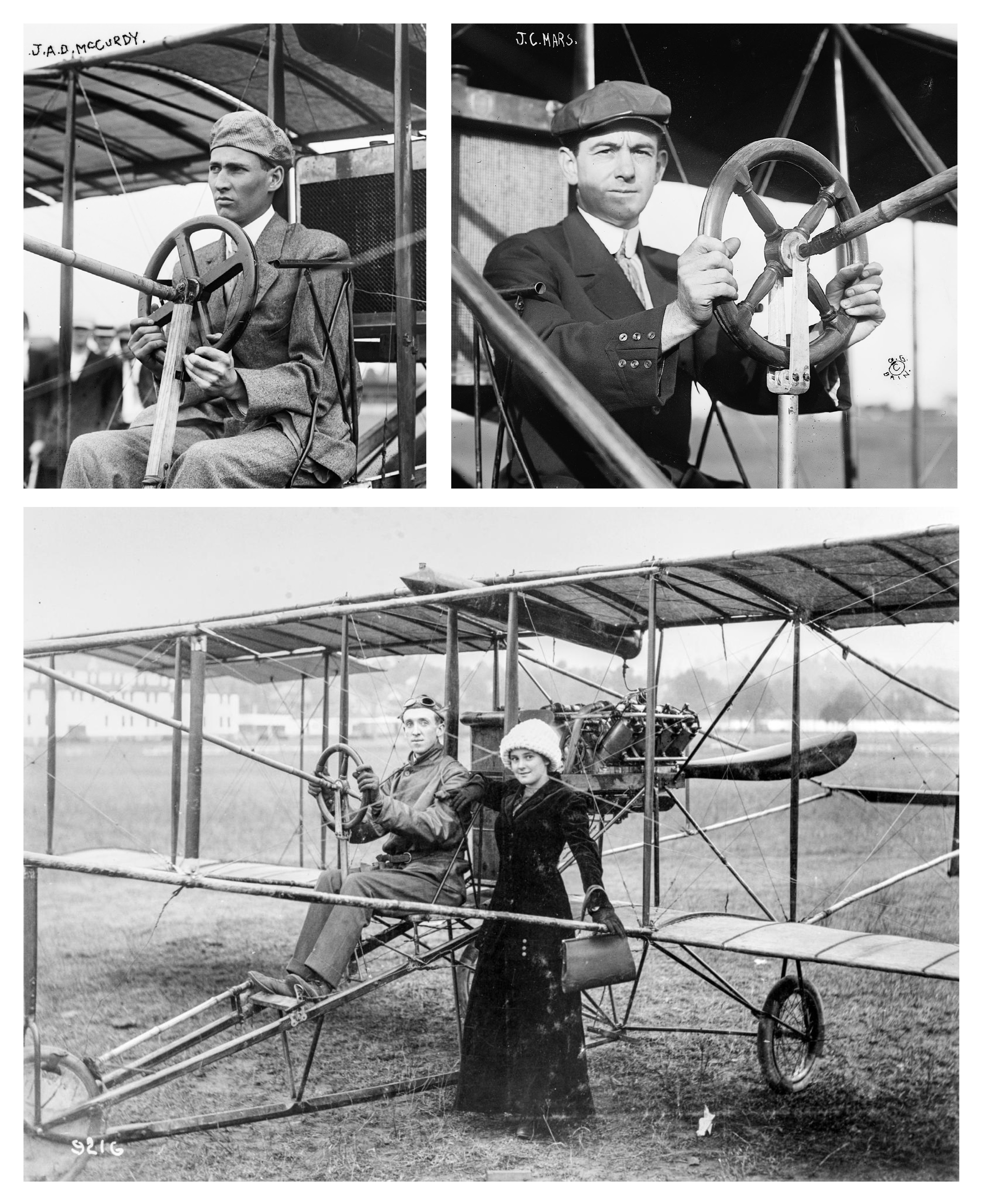

3) Despite this, Postmaster General Frank Hitchcock - a great fan of aviation - personally undertook to be a passenger in a Blériot monoplane at the air parade held in Baltimore on November 1, 1910. After the landing, he declared: "It will not be long before we are carrying the mails this way, that is certain", and on the same day he authorized the first official airmail delivery attempt, from aboard the German KAISERIN AUGUSTE VICTORIA, an ocean liner traveling on the high seas from America to Europe. Based on an agreement between an American daily newspaper "New York World" and the Hamburg-America Line shipping company, the Canadian John Alexander Douglas McCurdy (son of Alexander Graham Bell's secretary) had to lift an American-made Curtiss airplane into the air, from a 100-foot (30.5 m) long platform, installed on the bow of the ship navigating in 50 miles (92.5 km) distance from the shore. The platform was built on the bow of the ship, because the speed of the ship and the plane going in the same direction were added together, which shortened the take-off distance and increased the chance of a successful take-off. However, the attempt scheduled for November 5 was canceled due to bad weather (a fierce north-easterly gale damaged all the aircraft in the air parade, including McCurdy's, so he could not carry out the task), even though - if successful - this would have been the first case in history for an aircraft to take off from a ship's deck.

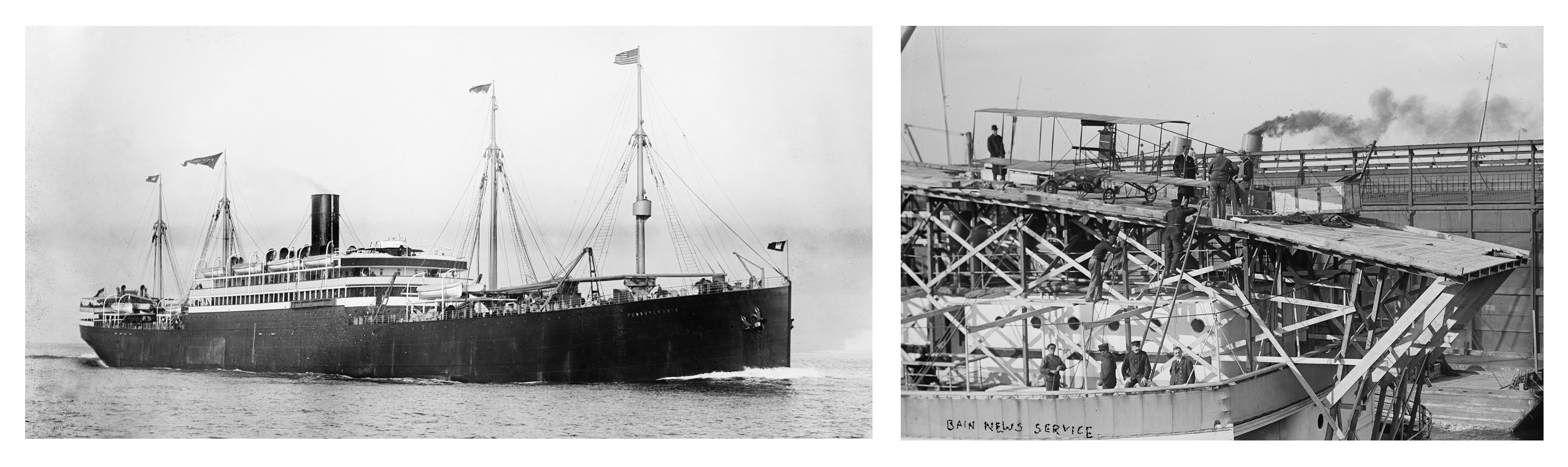

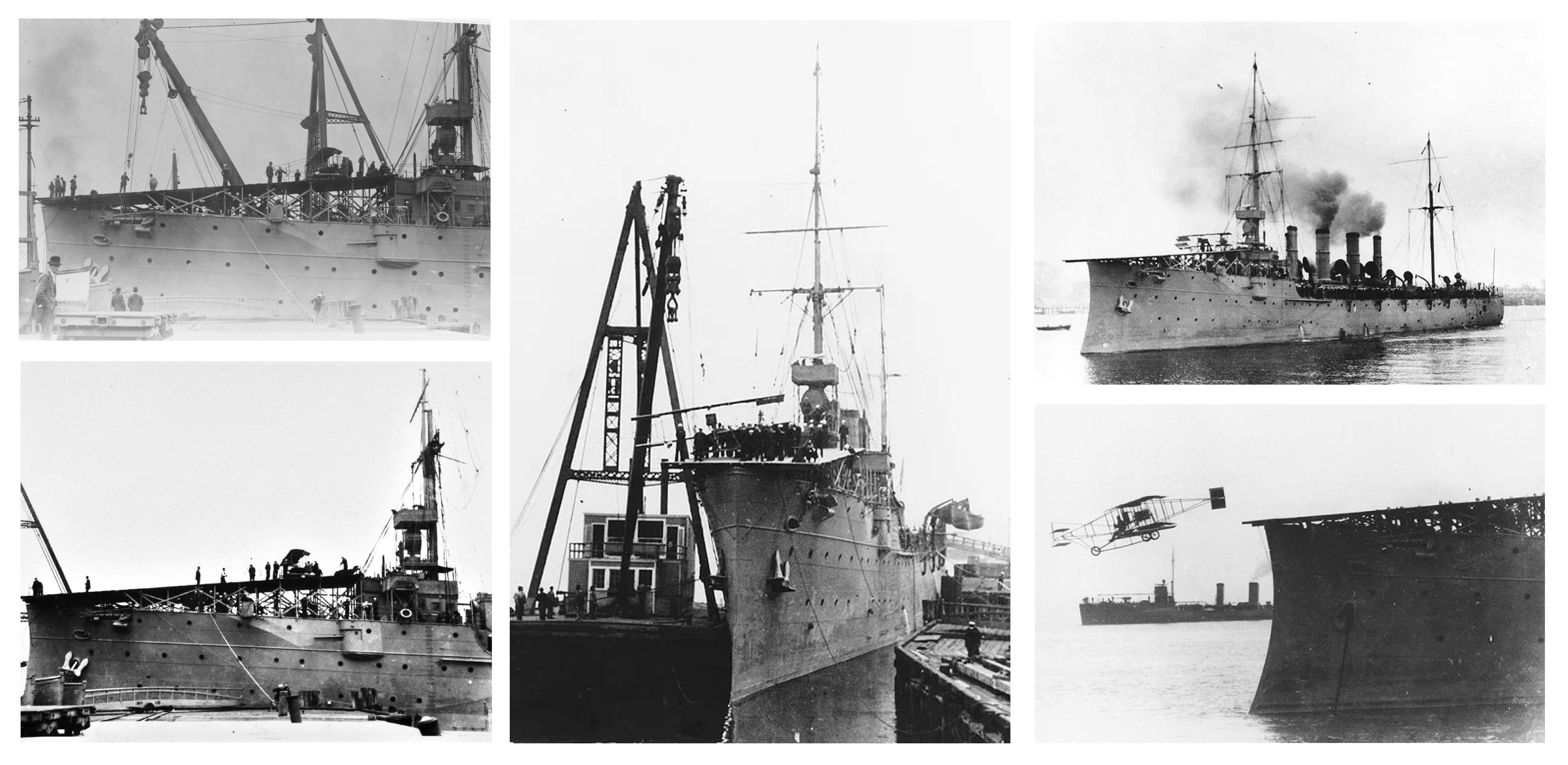

Fig. 3: Contemporary newspaper articles in The New York Times about the KAISERIN AUGUSTE VICTORIA and the experimental flight to be carried out on her board (source: here and here, drawing: Dr. Tamás Balogh © 2020).4) Since the experiment also had a hidden military aspect - the Curtiss company, which provided the aircraft for the experiment, hoped to get a naval order due tot the demonstration of its efficiency: "an aircraft can be launched from the deck of a ship while the ship is in motion." – Curtiss had no intention of giving up the priority, so on November 7 it was announced that the attempt would be repeated 5 days later on board another German ocean liner, PENNSYLVANIA, which was about to set sail. However, this ship was not only significantly smaller and slower than KAISERIN AUGUSTE VICTORIA, but her design only allowed for an 85-foot (26 m) long launch platform to be built on the top of her stern superstructure instead of the ship's bow. This meant that the ship's engines, 8 miles (15 km) east of Fire Island, had to be put into reverse to allow McCurdy to take off safely in a 10-knot (18.5 km/h) headwind. The plane then had to follow a 50-mile (92.6 km) route along the coast of Long Island to Governors Island, New York, where it could collect a $500 prize offered by businessman John Barry Ryan. The tension was heightened by the fact that, on November 9, the US Navy also prepared for the first successful shipboard aircraft launch, when, at the suggestion of the other faction of the Curtiss company in direct negotiations with the Navy, preparations were made for the construction of a launch platform on board the cruiser USS BIRMINGHAM (At the initiative of Admiral George Dewey, who became famous in the Battle of Manila in 1898, the Navy purchased its first aircraft in June 1909, and from October 1909 it actively investigated the possibility of involving aircraft in the execution of the reconnaissance tasks of the fleet, for the first time in a period when the whole world was still 50 aircraft were in military service, but no one had ever managed to take off from a ship). On November 11 – one day before the scheduled date of the experiment – McCurdy crashed at an air show and, although not seriously injured, was unable to reach the Hoboken pier of the Hamburg-America Line in time, so Curtiss sent the 34-year-old James Cairn Mars, instead of McCurdy.

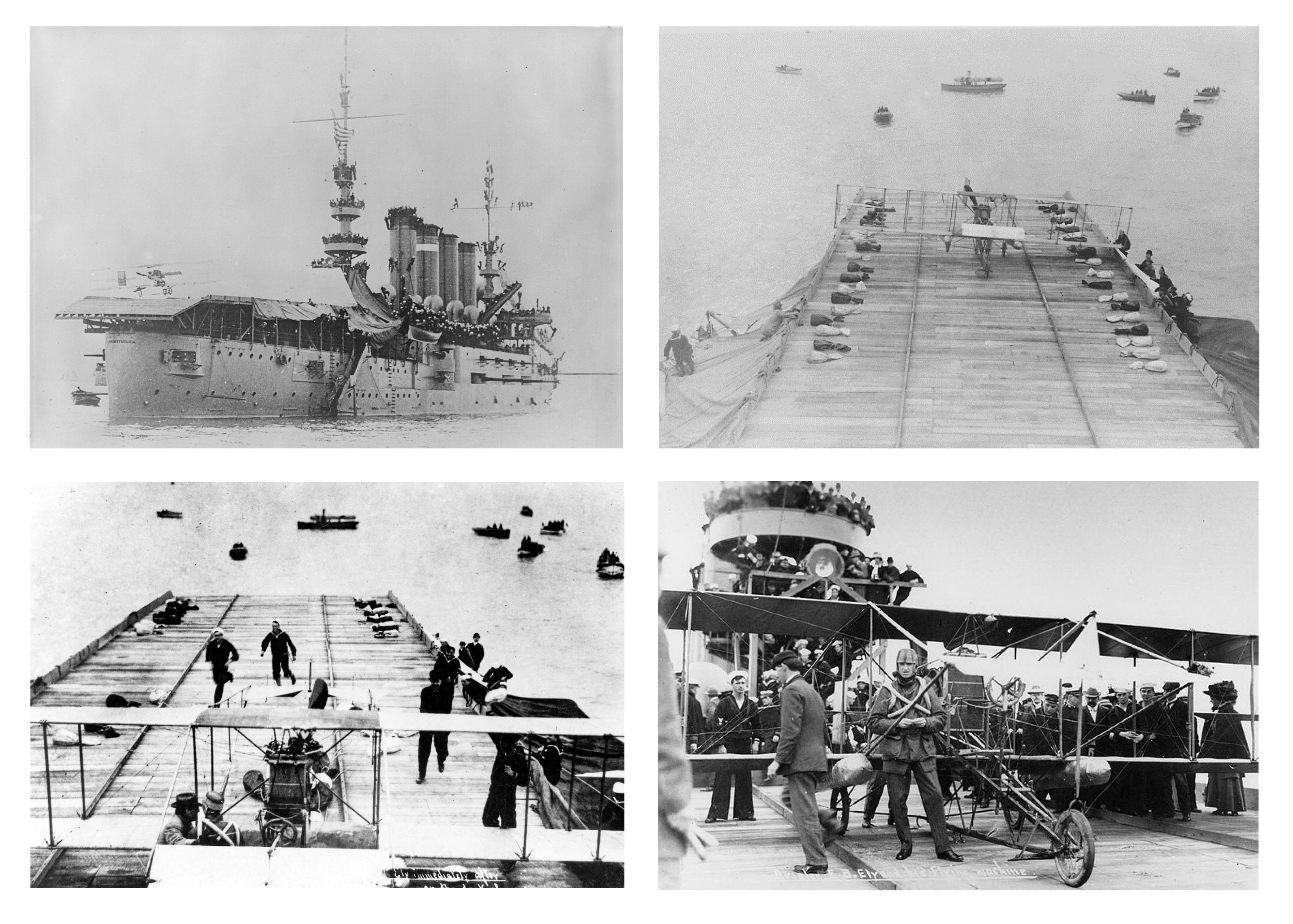

Fig. 4: The steamer PENNSYLVANIA and the launc platform installeed on her stern superstructure in Hoboken. Source: here and here.On November 11, one day before the test was scheduled to take place, McCurdy crashed at an air show, and although he was not seriously injured, he was unable to make it to the Hoboken pier of the Hamburg-America Line in time. So the 34-year-old James Cairn Mars co-pilot was alerted, who made a name for himself with his parachute jumps and as a pioneer pilot (he was the owner of the eleventh flying licence in the USA). The weather conditions turned out to be ideal this time, but a rubber tube – forgotten on the lower right wing of the plane – crashed into one of the wooden propeller wings in the vortex created after the propeller was started and broke off two smaller pieces, which flew out with great force and injured a sailor standing nearby, and they broke the steel wire leading to the aileron of the aircraft, making the plane uncontrollable and failing to take off. This is how it happened that the world's first successful shipboard aircraft launch finally took place 2 days later, when Eugene Burton Ely took off from the deck of the cruiser USS BIRMINGHAM, and then - in another attempt - made the first successful landing on the deck of the cruiser USS PENNSYLVANIA , on January 28, 1911, from which he took off again a few hours later that day.

Fig. 5: Pilots who were selected to be the first: J.A.D. McCurdy (1886-1961), J.C. Mars (1875-1944) and E.B. Ely (1886-1911), here were photographed together with his wife Mabel (source: here, here and here).

Fig. 6: Preparation of the cruiser USS BIRMINGHAM for the test, and E.B. Ely's first take-off from a ship (source: here, here, here, here and here).

Fig. 7: USS PENNSYLVANIA and E.B. Ely's first shipboard landing (source: here, here, here and here). As an interesting fact, in the second and third pictures you can see the sandbags placed opposite each other on the edge of the platform, which - more precisely, the ropes stretched between them - braked the landing plane. This type of cable brake system (together with the steam catapult shown in Fig. 9) is still a basic element of the operation of modern aircraft carriers.5) However, Postmaster General Hitchcock remained resolute. Pilot Earle Ovington was thus able to deliver the first airmail he had officially sent over a year later, on September 23, 1911 - but only on land instead of sea. Over the next few years, dozens of test flights were authorized at fairs, carnivals and air shows in more than 20 states. These flights convinced officials that airplanes could indeed carry mail. Beginning in 1912, therefore, postal officials petitioned Congress for the appropriation of funds to start an airmail service, which finally authorized the use of $50,000 in 1916 for this purpose. The government then issued requests for bids to contract providers in Massachusetts and Alaska, but received no acceptable responses. In 1917, the budget to establish an experimental airmail service was increased to $100,000 for the following fiscal year. So finally, in February 1918, the US Post Office issued a call for proposals for the purchase of airplanes, but the call was withdrawn a few weeks later, as the air mail service wanted to be operated by the Army Signal Corps in order to increase the number of flight hours and to improve training of its pilots. The scheduled air mail service finally started following the agreement of the postmaster general and the secretary of war on May 15, 1918, with planes and their pilots lent by the army.

Fig. 8: Postmaster General Frank Hitchcock hands pilot Earle Ovington the first official United States airmail shipment (top left), delivered by the pilot in his Blériot monoplane (top right). The first scheduled airmail shipment leaves Philadelphia (below left) and is picked up by local postmaster Thomas G. Patten from Lt. Tory Webb in New York (below right). Source: for all images here.The idea arise again:

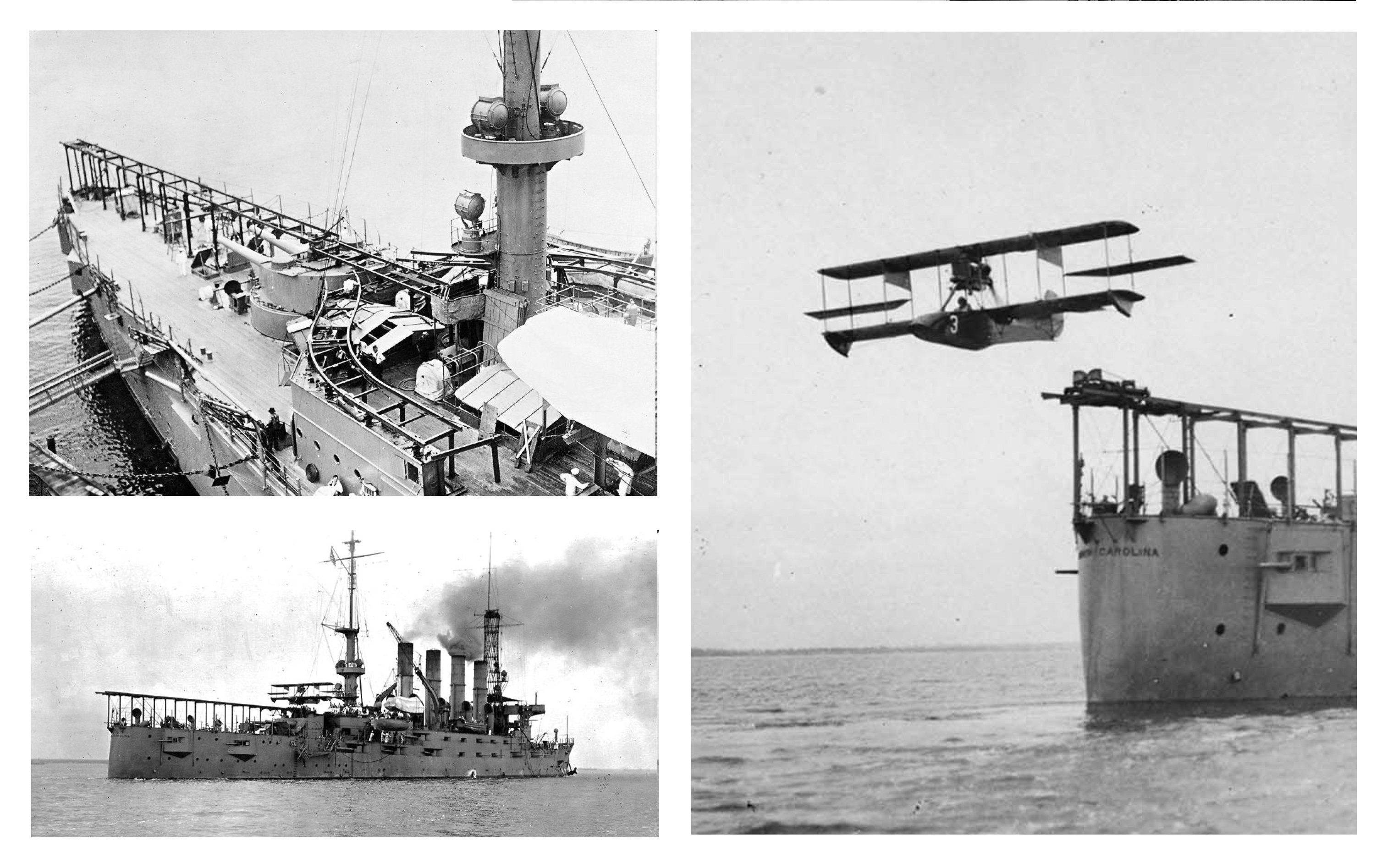

Airmail delivery started and became regular on the continent, but the problem of airmail delivery from shore to ships on the high seas, and from ships to shore, remained unsolved. In the First World War, warplanes serving with the navies, but without on-board radios, were sometimes forced to drop important message to their own warships in battle, but this solution was considered more of a feat and a particularly lucky coincidence than a reliable technical solution. (In the naval battle at the Otranto Strait on May 15, 1917, for example, the Austro-Hungarian naval flying boat K-195 (piloted by Emmanuel Lerch and Béla Lenti) dropped a report in a tin box on the position of the cruiser NOVARA, damaged in the battle, barely from the altitude of 5 m onto board the armored cruiser SANKT GEORG, the lead ship of the relief forces, rushing to the scene of the battle with full steam. Thanks to the courage and knowledge of the pilots, the report reached its destination despite the strong wind blowing at the site.) The development and implementation of such a solution was made difficult by the fact that, although the very first airplane takeoff from a ship's deck took place in 1910, no one had yet taken off from a moving ship (the USS BIRMINGHAM was at anchor at the time of E.B. Ely's experiment). Nevertheless, the new world record did not have to wait long. Although the first Curtiss experiments which were planned with the involvement of German ocean liners already wanted to carry out the task of taking off from ships that were in motion, during the war, for understandable reasons, the Germans could not really be persuaded to do such a thing. The United States, on the other hand, did not have ocean liners large enough to continue the experiments independently. Thus, the cruiser USS NORTH CAROLINA became the first ship in history to launch an airplane while underway, using its onboard steam catapult, in Pensacola, Florida on November 5, 1915. Designed by Glenn Curtiss of San Diego, AB2 was piloted by Corvette Captain Henry C. Mustin. (Eugene B. Ely's takeoffs on November 14, 1910 and January 8, 1911 did take place from a ship deck launch platform, but his takeoff was not assisted by a catapult). The experiments carried out on the cruiser proved that with the help of platforms of suitable size installed on board ships, not only the launch of aircraft on the ship deck, but also their landing - thus the transport of passengers and/or goods (mail) by air and sea - can be ensured.

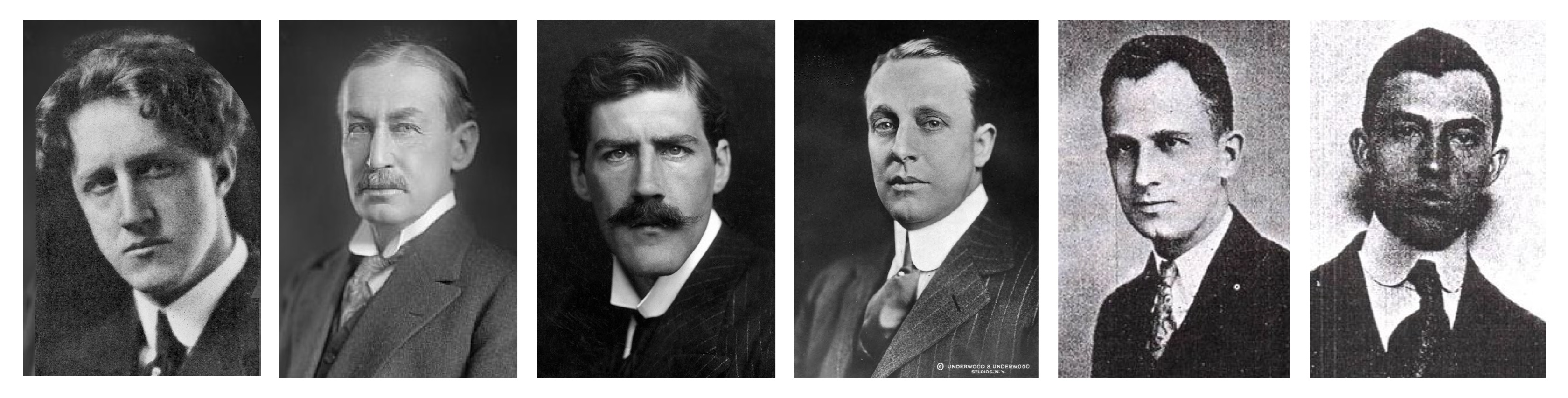

Fig. 9: Take-off assisted by a steam catapult from the deck of the USS NORTH CAROLINA. Although the airplane is an American invention, the domestic public was initially uninterested in it, and the Wright brothers were distracted from further development by the multitude of patent lawsuits. As a result, America entered the First World War without having its own planes that could be used reliably, it had to buy French planes, and they tried to make up for the backlog with military-initiated developments (source: here, here and here).The idea came from Waldemar Kaempffert, the editor-in-chief of Popular Science Monthly, the American science popularization magazine of the time, who turned to Postmaster General Albert Sidney Burleson, who had been in office since 1913. The postmaster supported the initiative and ordered his second deputy, Otto Praeger, to carry out the necessary organizational tasks. Praeger entered into a relationship with New York postmaster Thomas G. Patten, who proved to be an ideal partner for the attempt: he won the support of David Lindsay, executive of the International Mercantile Marine Co. (IMMC) - the American-owned group that owns the White Star Line shipping company registered under British law - and Governor of the Maritime Transport Associationby. In the meantime, Kaempffert made an agreement with the famed American businessman of the time, Inglis Moore Uppercu, an investor in aircraft, car and motorcycle production, who founded the first regular passenger transport airline in 1919, Aeromarine Airways, and recognized the excellent advertising opportunity. The task of implementing the idea was given to Paul Gerhard Zimmermann (1890-1962), chief engineer of the Aeromarine company, and his brother, pilot Cyrus Johnston Zimmermann (1892-?), took the main role in the implementation. They both started in the automotive industry, and during the First World War they started working in aviation. In 1917 they were employed by the Curtiss Airplane and Motor Co., Buffalo, and in 1918 joined the Aeromarine Plane and Motor Co., where Paul became chief engineer and Cyrus became chief test pilot.

Fig. 10: The key figures of the experiment: Waldemar Kämpffert, editor-in-chief of Popular Science Monthly; Thomas G. Patten, Congressman, Postmaster of New York; David Lindsay, 27th Earl of Crawford, British Secretary of State for Transport 1916-1920; Inglis Moore Uppercu, Owner-CEO of Aeromarine; Chief designer Paul Gerhard Zimmermann and test pilot Cyrus Johnston Zimmermann (source: here, here, here, here, here and here).The big experiment:

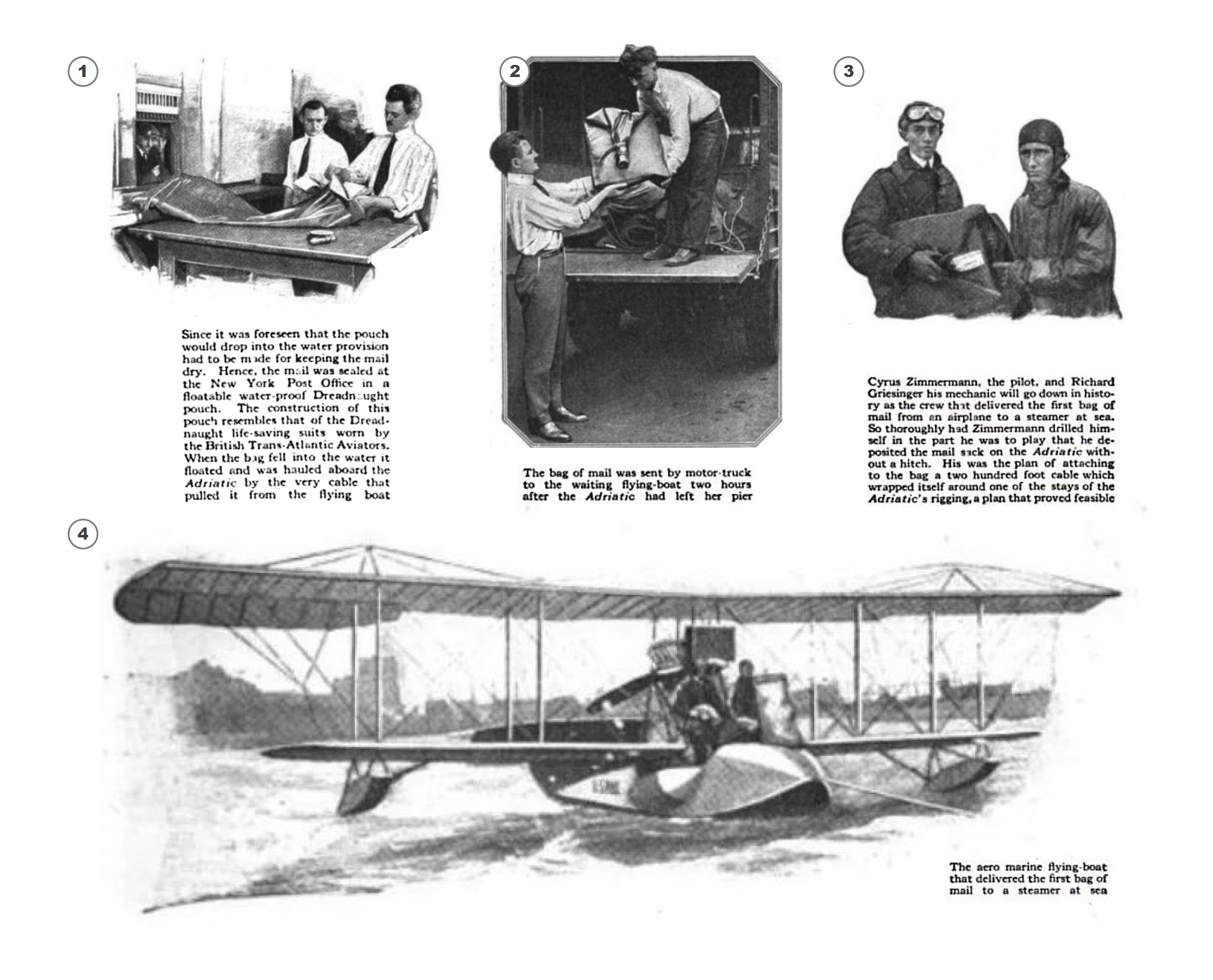

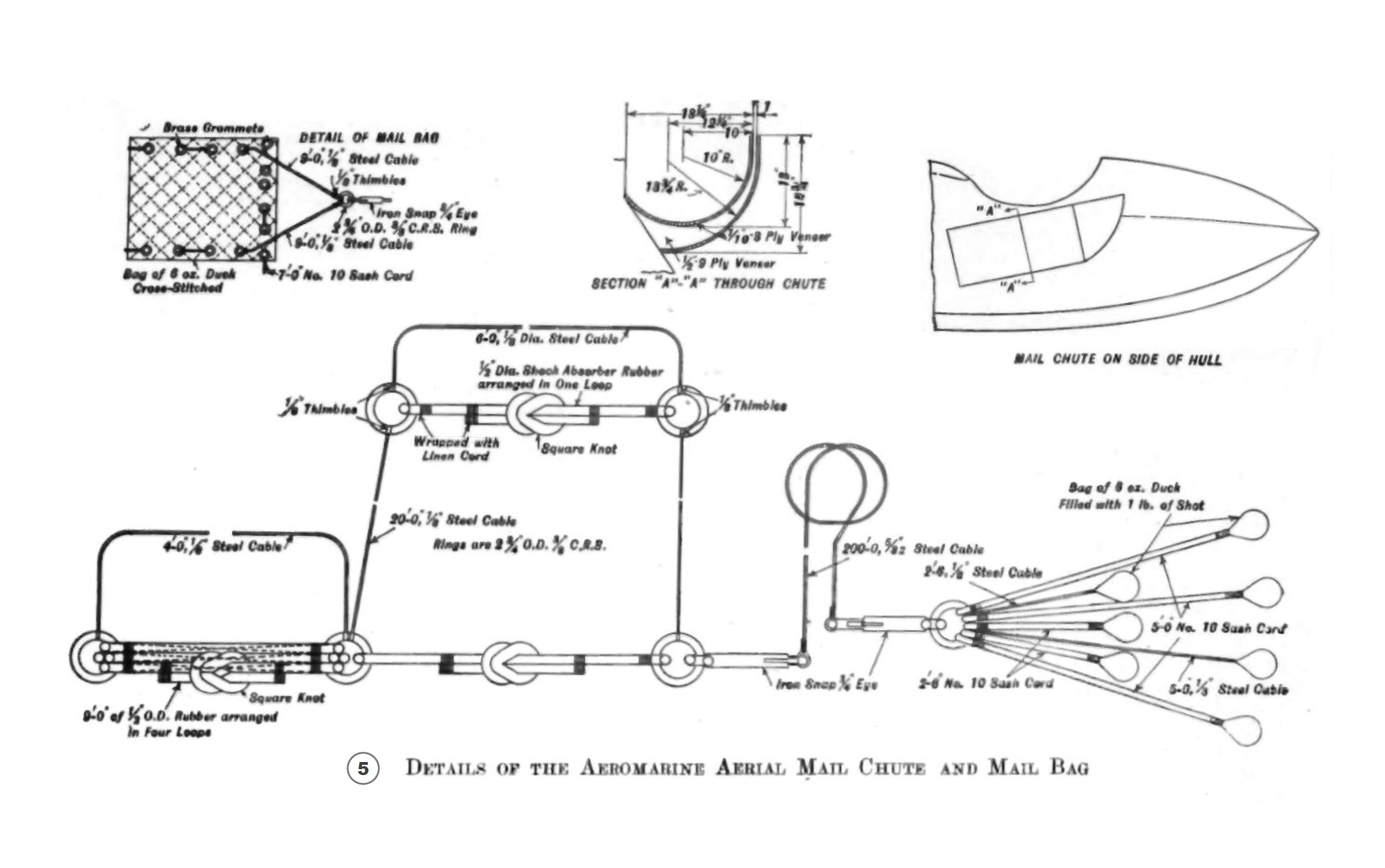

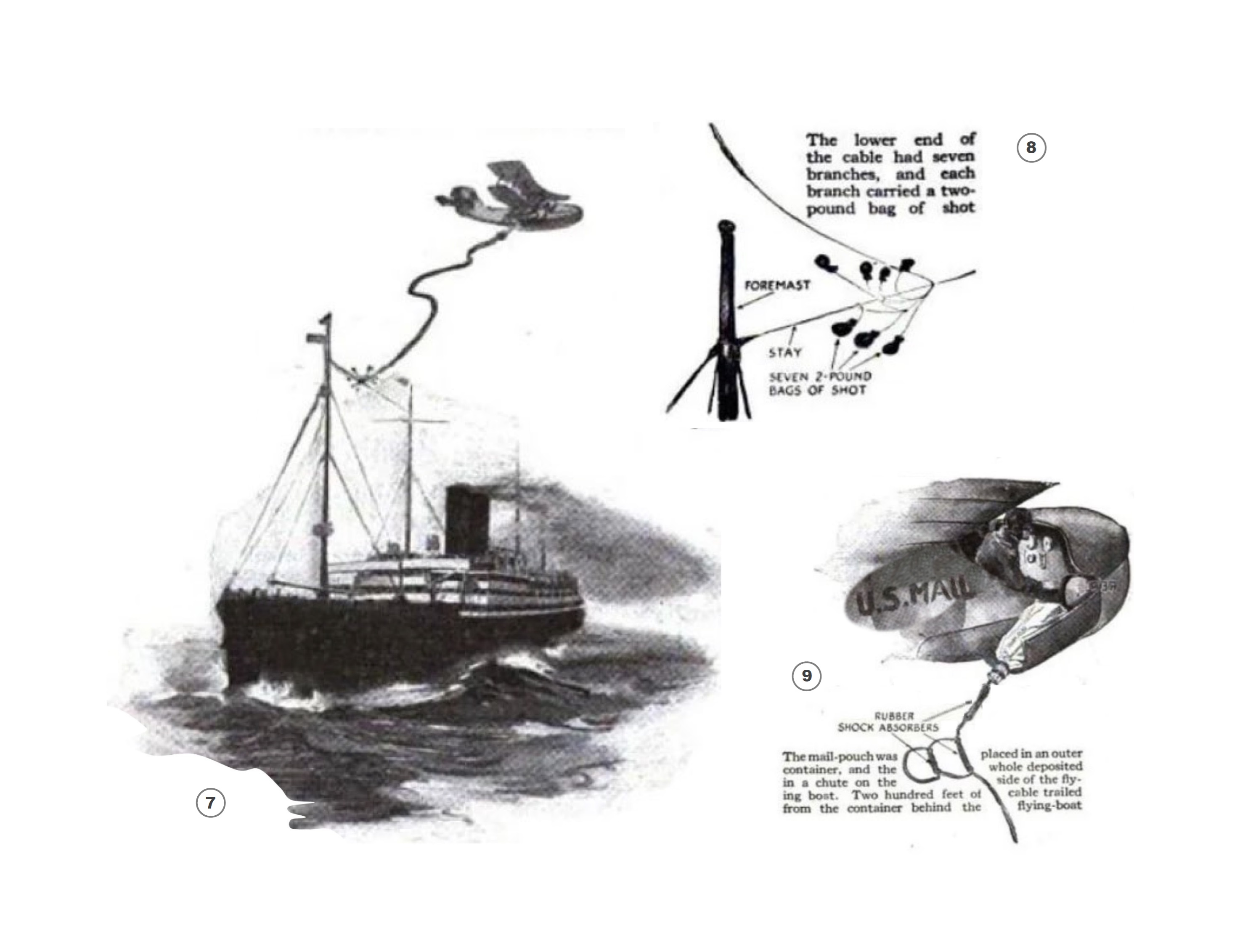

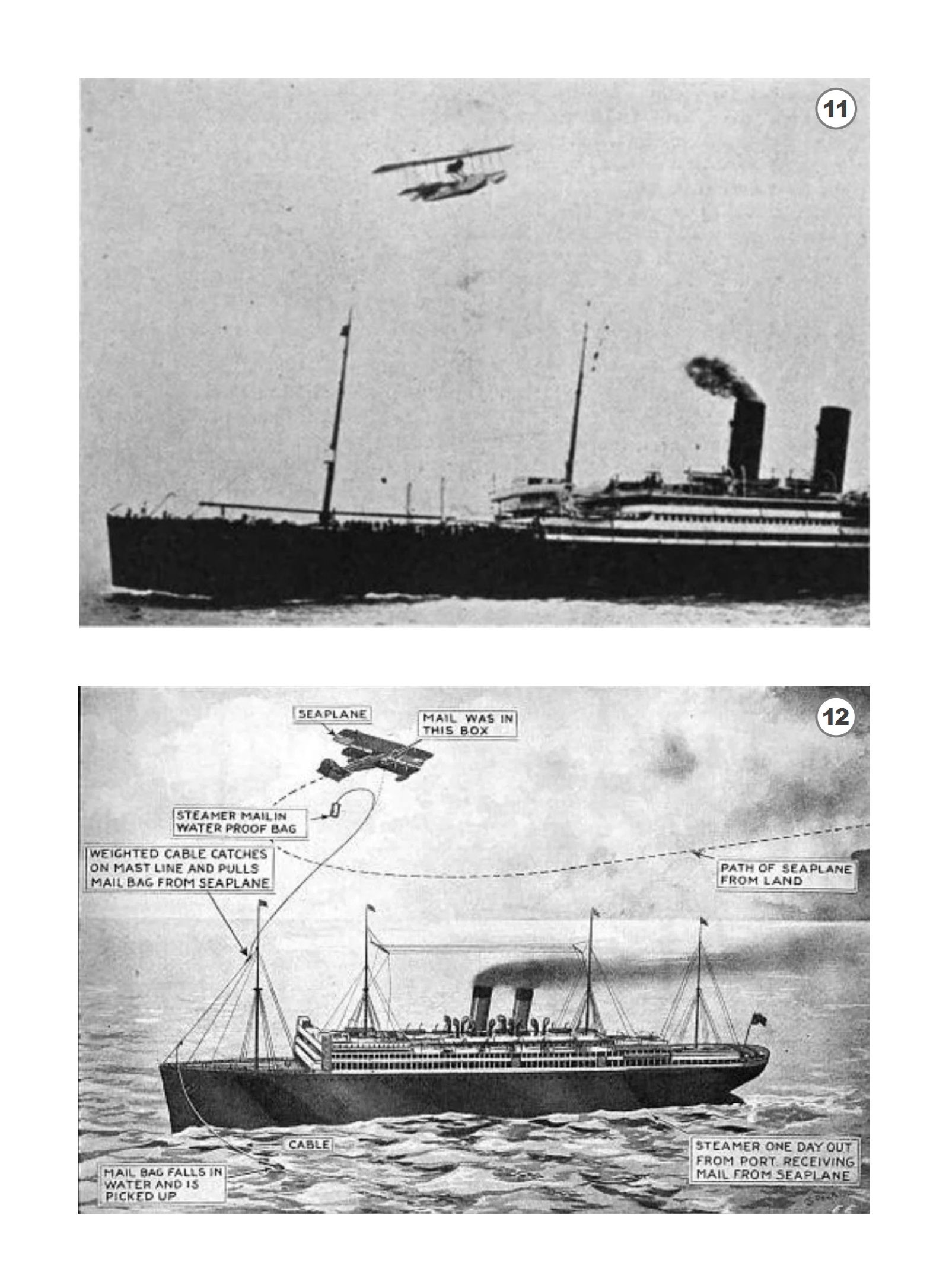

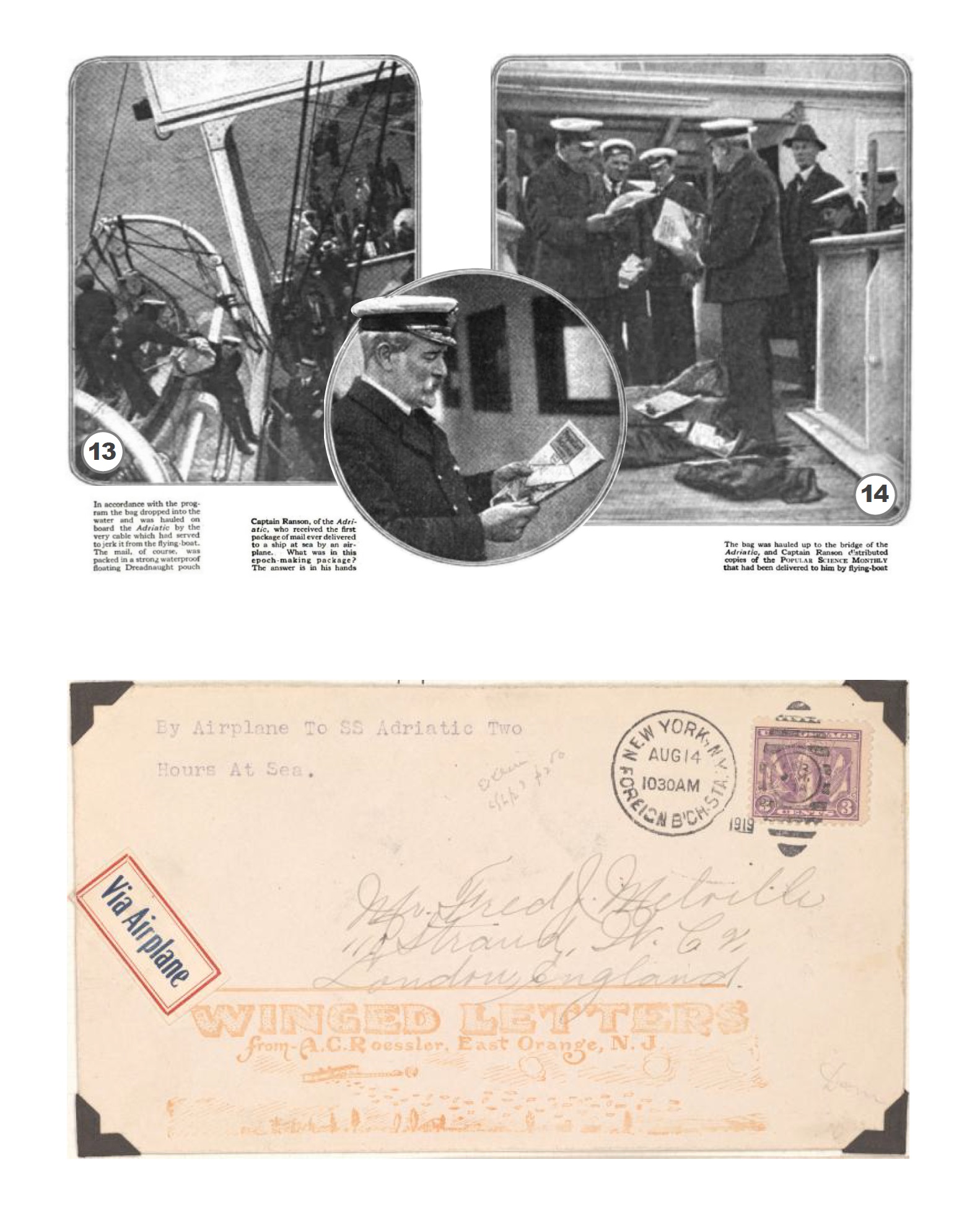

To prepare the experiment, the stakeholders formed committee to determine the details of the implementation. IMMC undertook to involve White Star Line's steamer ADRIATIC (which was arriving in New York on her first civilian voyage after World War I) in the experiment, while the Aeromarine company offered one of its newest flying boats (8.8 m long, 14.8 m span, biplane model 40C equipped with a 100 HP Curtiss engine, which could fly 403 km at a speed of 114 km/h). The organizing committee finally decided on an action to be carried out with the cooperation of the ship and the aircraft. The essence of this was that the aircraft crew should not simply drop the mail bag onto the ship (since the almost 50 kilo mail bag could have caused serious personal injury if it fell onto a deck crowded with passengers), but attach it to a cable, and only connect the cable on the ship, and let the bag at the other end of the cable fall into the water near the ship, from where the ADRIATIC's crew will be able to take him on board easily by the cable attached to the ship. For the idea to work, it was necessary to design the cable in such a way that it could be attached to the ship, the mail bag had to be waterproof, and perfect timing also required from the pilots.

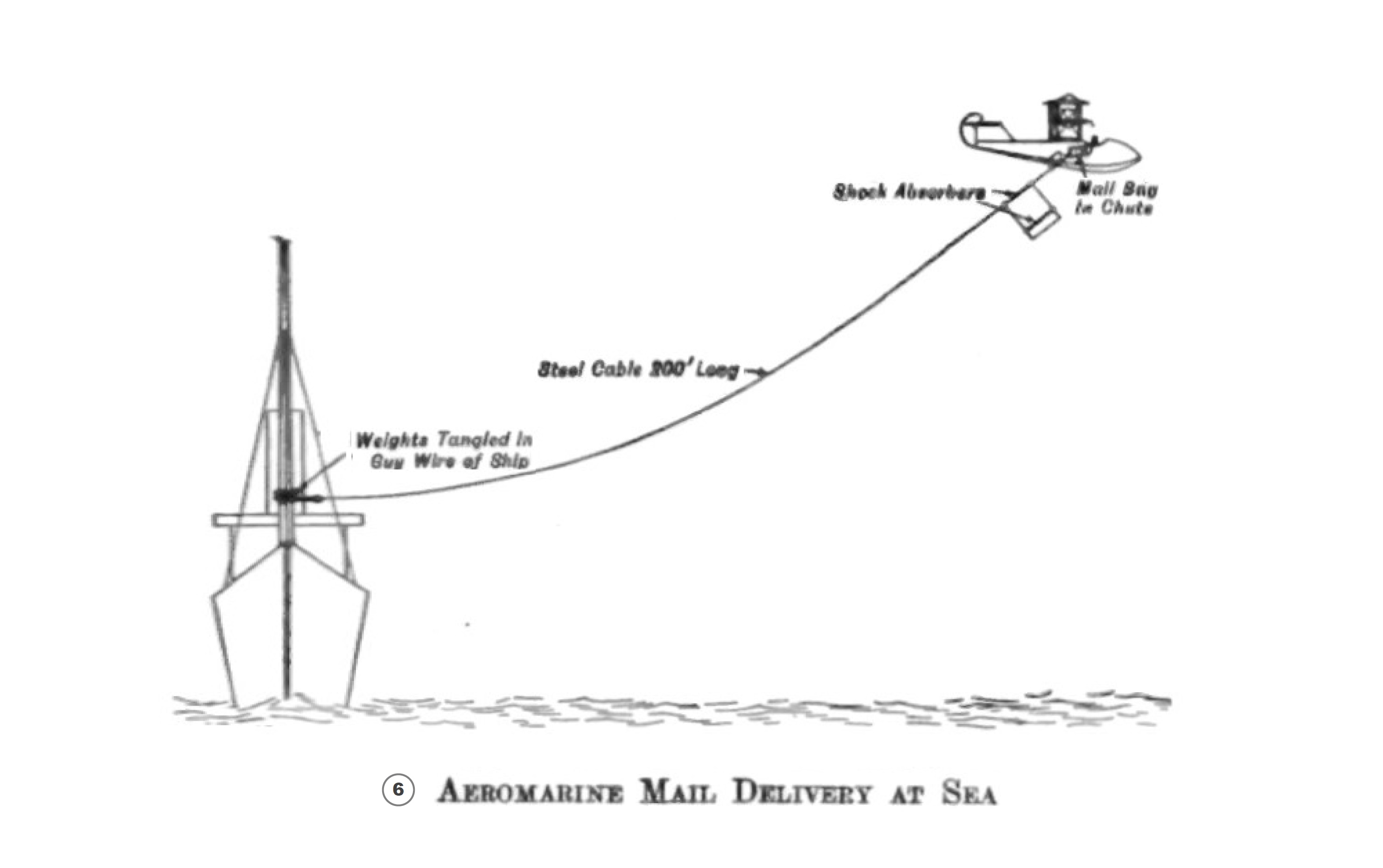

The proper design of the cable was ensured with two solutions: On the one hand, the free end of the cable was designed as divided into seven branches, and shot-filled 1 kg bags was attached to each branch as a counterweight. On the other hand, a strong rubber shock absorber was mounted on the other end of the cable attached to the mail bag. The idea was for the aircraft to fly across over the ship, while hangs the 60 m long cable down and tows it behind itself at a low altitude. As soon as the cable hits the rigging of the ADRIATIC, the seven branches of the free cable end with the attached counterweights, obeying the force effect resulting from the sudden stop - in the direction opposite to the plane's direction of travel - are wrapped around the ship's rigging, in this way creating the necessary connection between the ship and the mail bag attached to the other end of the cable on an airplane. As the plane flies further and further away from the ship, the cable entangled in the rigging tightens, and finally pulls the mail bag placed there from the chute-like container on the side of the plane, which falls under its own weight into the water next to the ship, from where the cable entangled in the rigging can be picked up by the ADRIATIC's crew. The shock absorber at the other end of the cable attached to the mail bag was used to prevent the breaking off the towed cable from the mail bag, during the suddenly stop when it hits the ship's rigging (or at the accompanying fast and strong jerk). For this purpose the shock absorber was made of solid rubber like the wheels of airplanes. This solution alowed the slight stretching of the cable without having to worry about breaking it off.

The integrity of the postal items was ensured by a waterproof pouch made of vulcanized rubber that could be closed with a buckle and a padlock, in which the mail bag was packed. The cable used for the delivery was attached to this pouch. The pouch was made in such a way that the thicker and heavier layer of rubber placed on the bottom served as a float to keep the pouch in a vertical position while floating in the water. In the floating position, two-thirds of the pouch was submerged and only one-third rose above the water level. Around 400 letters could be placed in the mail bag.

The functionality of the plan depended on the pilot, who had to descend so low with his plane that the 60-meter-long cable being towed behind it could come into contact with the rigging of the ADRIATIC. In other words, the pilot had to get dangerously close to the ocean liner without crashing his plane.

The experiment was carried out on August 14, 1919. ADRIATIC left New York half an hour late after the announced departure time of 12:00 noon. The Aeromarine 40C took off almost two hours after the steamer's departure, in strong gale, but overtook the ADRIATIC just as it was passing out of the Ambrose Channel. The plane made two circles above the liner, then decreased its altitude and when it approached the ocean liner to within 30 meters, pilot Zimmermann released the cable, which, during the flight across over the ship, wound itself on the ship's rigging as planned, pulling the mail bag packed in a waterproof pouch out from the chute attached to the side of the aircraft. The mail bag fell into the water next to the ADRIATIC, from where the ship's sailors fished it out and brought it to the bridge in front of the captain.

Fig. 11: Illustrations of the contemporary press (source: here).

Fig. 12: Devices designed for air-sea mail delivery: the waterproof pouch, the chute attached to the side of the airplane and the weighted branch rope (source: here)

Fig. 13: Illustration of the experiment: 6) A branch rope with a counterweight at the lower end is wrapped around the rigging of the ship, the force of the pulling of the 60 m long cable is eliminated by shock absorbers at the upper end of the cable, at the same time pulling the pouch containing the mail bag out of the chute-like container attached to the side of the aircraft (source: here).

Fig. 14: Illustrations of the contemporary press (source: here).

Fig. 15: The seaplane catches up and overtakes the ADRIATIC (source: here). Fig. 16. and 17: Above: The moment of the flight across over the ship and the release of the cable (source: here). Below: Illustration of the experiment in "Electrical Experimenter" magazine (source: here).

Fig. 16. and 17: Above: The moment of the flight across over the ship and the release of the cable (source: here). Below: Illustration of the experiment in "Electrical Experimenter" magazine (source: here). Fig. 18. and 19.: Above: Shots of the mail delivery (source: here). Below: A letter from the mail bag of the first air-sea mail delivery (source: here).

Fig. 18. and 19.: Above: Shots of the mail delivery (source: here). Below: A letter from the mail bag of the first air-sea mail delivery (source: here).The Aeromarine company benefited from the success of the experiment according to the plans of the owners: on August 21, 1919 (a week after the successful completion of the experiment), its flying boats were already carrying out civilian passenger transport (a New York businessman in a hurry was transported from New York to Poughkeepsie along the Hudson River and back), they undertook the same thing in October, but already between New York and Havana, and by the end of the year they also opened the first New York city sightseeing flights. The company grew rapidly: in 1920, it acquired the Florida-West Indies Airlines, and then entered into a contract with the government to deliver airmail to Cuba (this was the very first international airmail contract in US history). Aeromarine developed the AM-1, 2, and 3 types of aircraft to take advantage of rapidly expanding opportunities (such as the night flights for mail delivery).

Following the success of the experiment, White Star Line put forward the prospect of making the solution regular on its ships. Seeing the significant difference in speed between a fast airplane and a ship that only trudges along in comparison, some expressed the possibility that airplanes could soon make passenger ships obsolete in intercontinental traffic (as soon as they become capable of transoceanic flight). However, more sober-minded professionals already warned that ships will always remain indispensable in the transport of large quantities of bulk goods. Although they could not predict when the transition in passenger transport would take place (when the very first long-distance aircraft, capable of flying across the Atlantic Ocean and carrying many passengers at the same time could be built), but they declared that seaplanes certainly will be useful additions to the equipment of ocean-going passenger vessels.

They were right: it really happened that way. However, this is another story.

Fig. 20: Cyrus Johnston Zimmermann flies his plane directly opposite the ADRIATIC after catching up with her and just before starting the turn that ended with the successful delivery of the mail (source: here).It would be great if you like the article and pictures shared. If you are interested in the works of the author, you can find more information about the author and his work on the Encyclopedia of Ocean Liners Fb-page.

If you would like to share the pictures, please do so by always mentioning the artist's name in a credit in your posts. Thank You!

Sorurces:

[1] Phillippa Stewart (2015): Barnstorming used to be way more dangerous…

https://www.redbull.com/gb-en/barnstorming-used-to-be-way-more-dangeros[2] Stephen Kochersperger (2018): Airmail – a Brief History, https://about.usps.com/who-we-are/postal-history/airmail.pdf

[3] Sz.n. (1910): To Fly Aeroplane from Ocean Liner [New York Times, 3 November 1910], https://www.loc.gov/resource/mss46706.05003463/?sp=1&st=image&pdfPage=1&r=-1.293,4.345,3.586,1.633,0

[4] Dr. Greg Bradsher (2020): The First Aeroplane Take Off from a Ship, November 14, 1910., https://text-message.blogs.archives.gov/2020/08/11/the-first-aeroplane-take-off-from-a-ship-november-14-1910-part-i/

[5] M. C. Farrington (2016): How One Piece of FOD Changed Naval Aviation History, https://hamptonroadsnavalmuseum.blogspot.com/2016/11/how-one-piece-of-fod-changed-naval.html

[6] John Hammond Moore (1981): The Short, Eventful Life of Eugene B. Ely, https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/1981/january/short-eventful-life-eugene-b-ely

[7] Sz.n. (1919): Air mail delivered for First Time to Steamship at Sea, in.: The New York Tribune, August 15, 1919, Page 16, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83030214/1919-08-15/ed-1/seq-16/

[8] Sz.n. (1919): Delivering Mail to Steamer After It Has Sailed, in. Scientific American Vol. CXXI. No. 8 August 23. 1919, https://ia802308.us.archive.org/7/items/sim_scientific-american_1919-08-23_121_8/sim_scientific-american_1919-08-23_121_8.pdf

[9] Paul G. Zimmermann (1919): The Aeromarine Aerial Mail Delivery System, in. Aviation and Aeronautical Engineering 1919.10.15, https://ia903404.us.archive.org/23/items/sim_aviation-week-space-technology_1919-10-15_7_6/sim_aviation-week-space-technology_1919-10-15_7_6.pdf,

[10] Sz.n. (1919): Seaplane delivers Ship Mail at Sea, in. Electrical Experimenter, 1919.10., https://www.worldradiohistory.com/Archive-Electrical-Experimenter/EE-1919-10.pdf,

[11] Sz.n. (1920): The Log of an Aeromarine. A Modern Adventure in Pathfinding, https://www.blindhorsebooks.com/pages/books/16340/aeromarine-plane-motor-company/the-log-of-an-aeromarine-a-modern-adventure-in-pathfinding-aviation-history

[12] Sz.n.: Aircraft Journal 1919 August 23, https://www.reddit.com/r/Oceanlinerporn/comments/zml4t9/information_about_rms_adriatics_air_mail_delivery/#lightbox

[13] Waldemar Kaempffert (1919): How the Popular Science Monthly dropped Mail on a Liner’s Deck, in.: Popular Science Monthly, October, 1919, https://archive.org/details/sim_popular-science_1919-10_95_4/page/84/mode/2up

[14] Sz.n.: Photos of Aeromarine aircraft, https://www.timetableimages.com/ttimages/aerompha.htm#miami

[15] Biographies of Aeromarine personalities, https://www.timetableimages.com/ttimages/aerombi1.htm#czim

[16] Sz.n. (1919): A Pioneering Experiment in Shore-to-Ship Mail Delivery, https://transportationhistory.org/2023/08/14/1919-a-pioneering-experiment-in-shore-to-ship-mail-delivery/

[17] 1919 first airplane delivery, shore to ship at sea cover,

https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e3-c560-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99 -

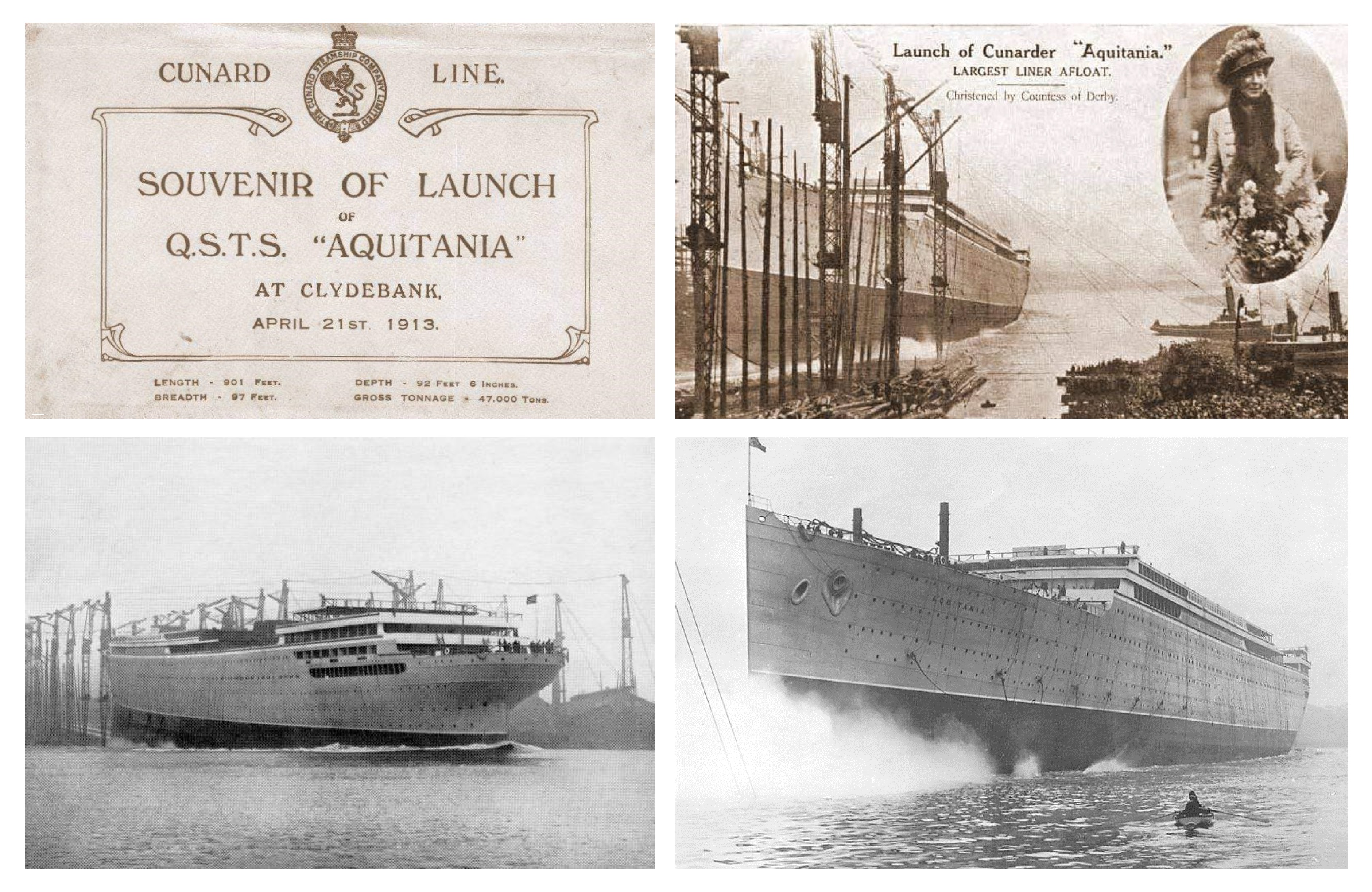

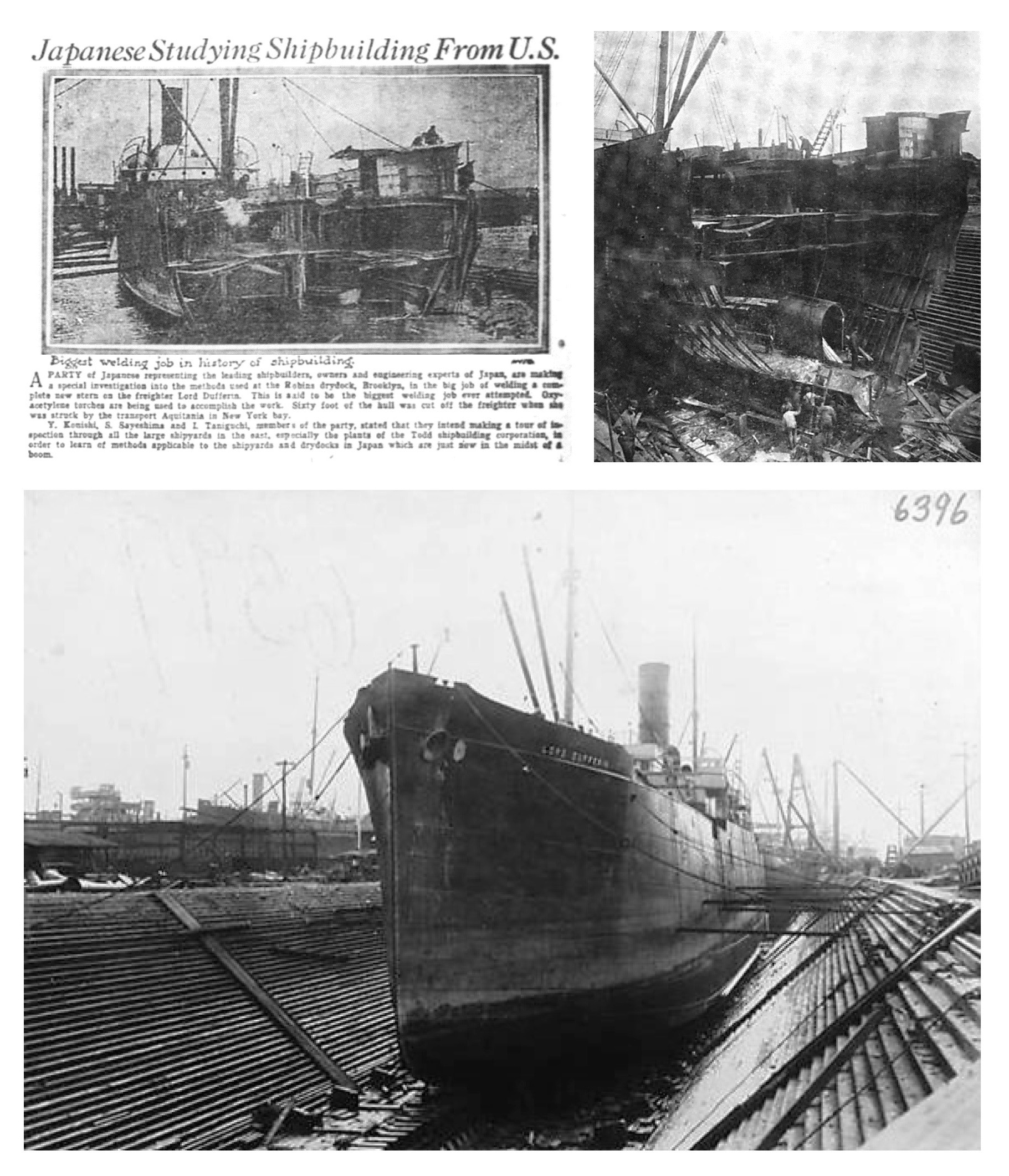

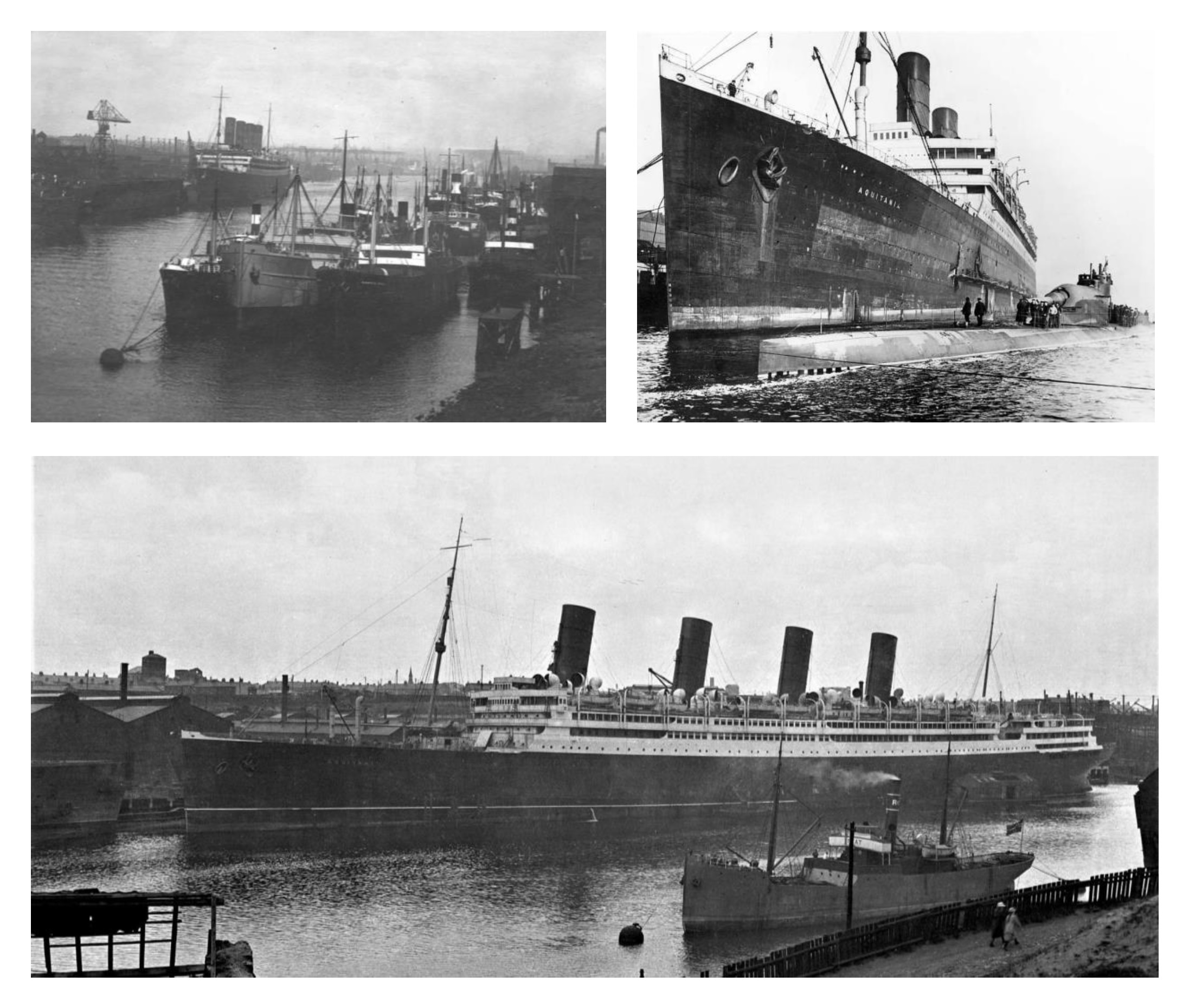

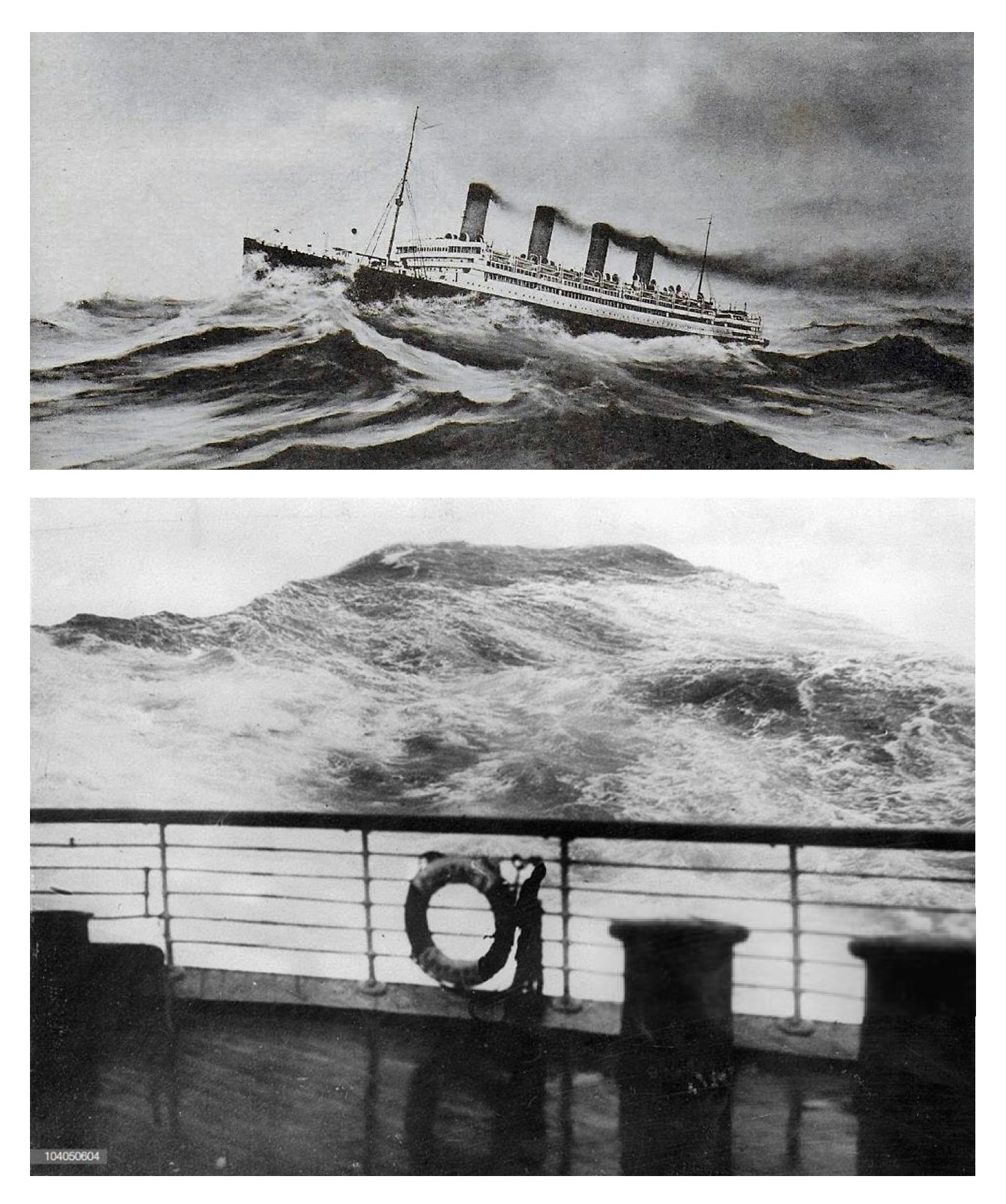

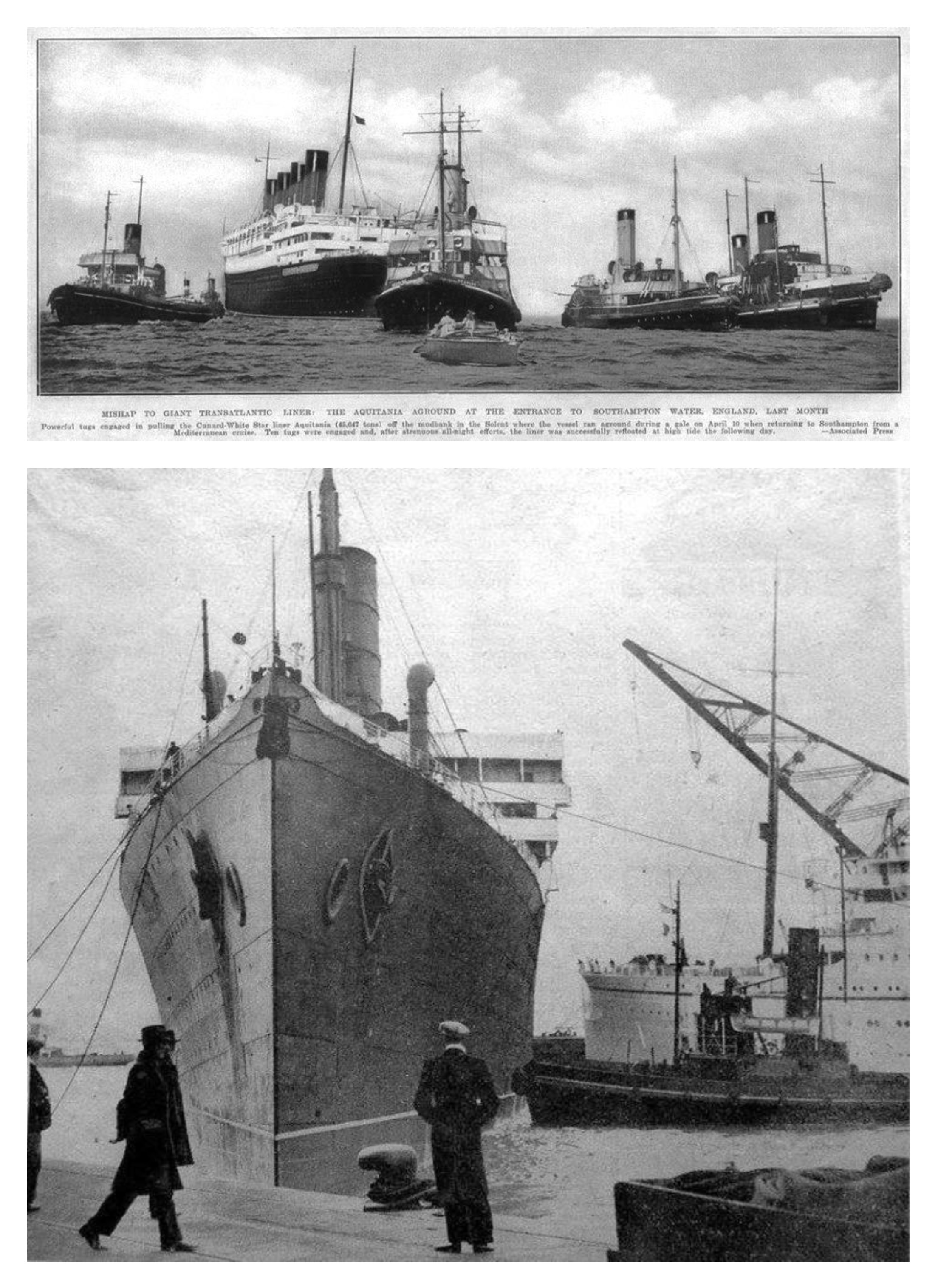

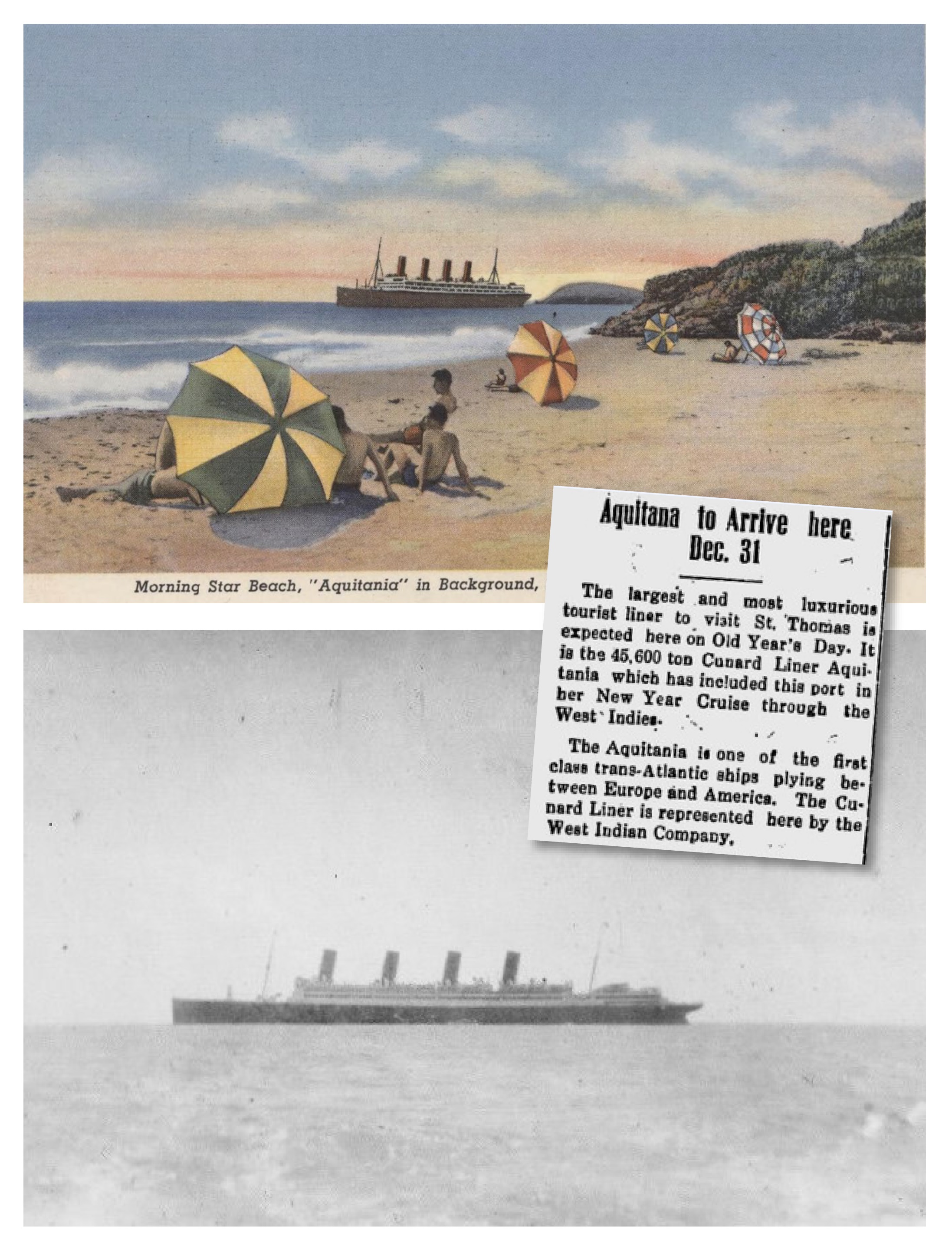

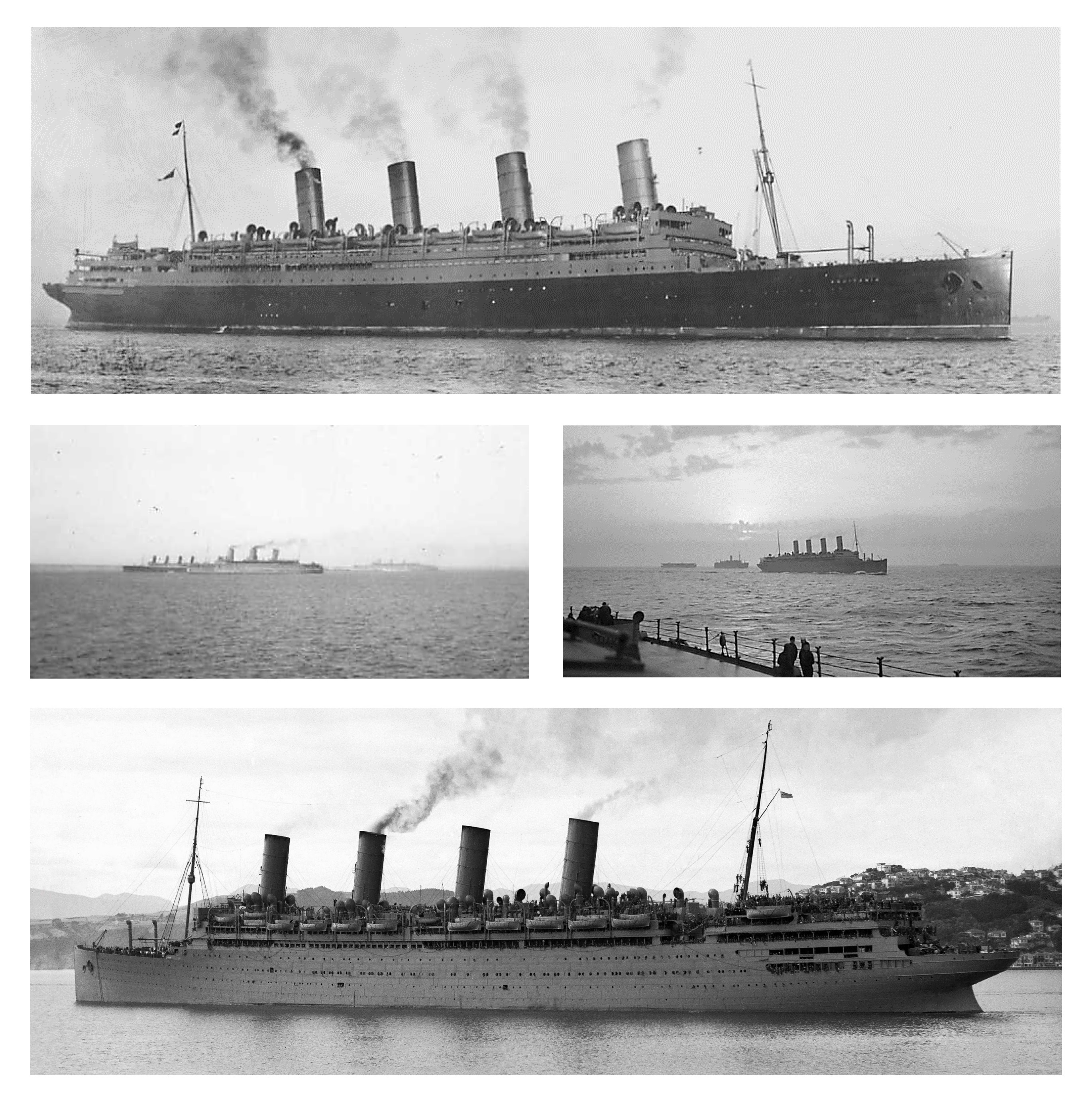

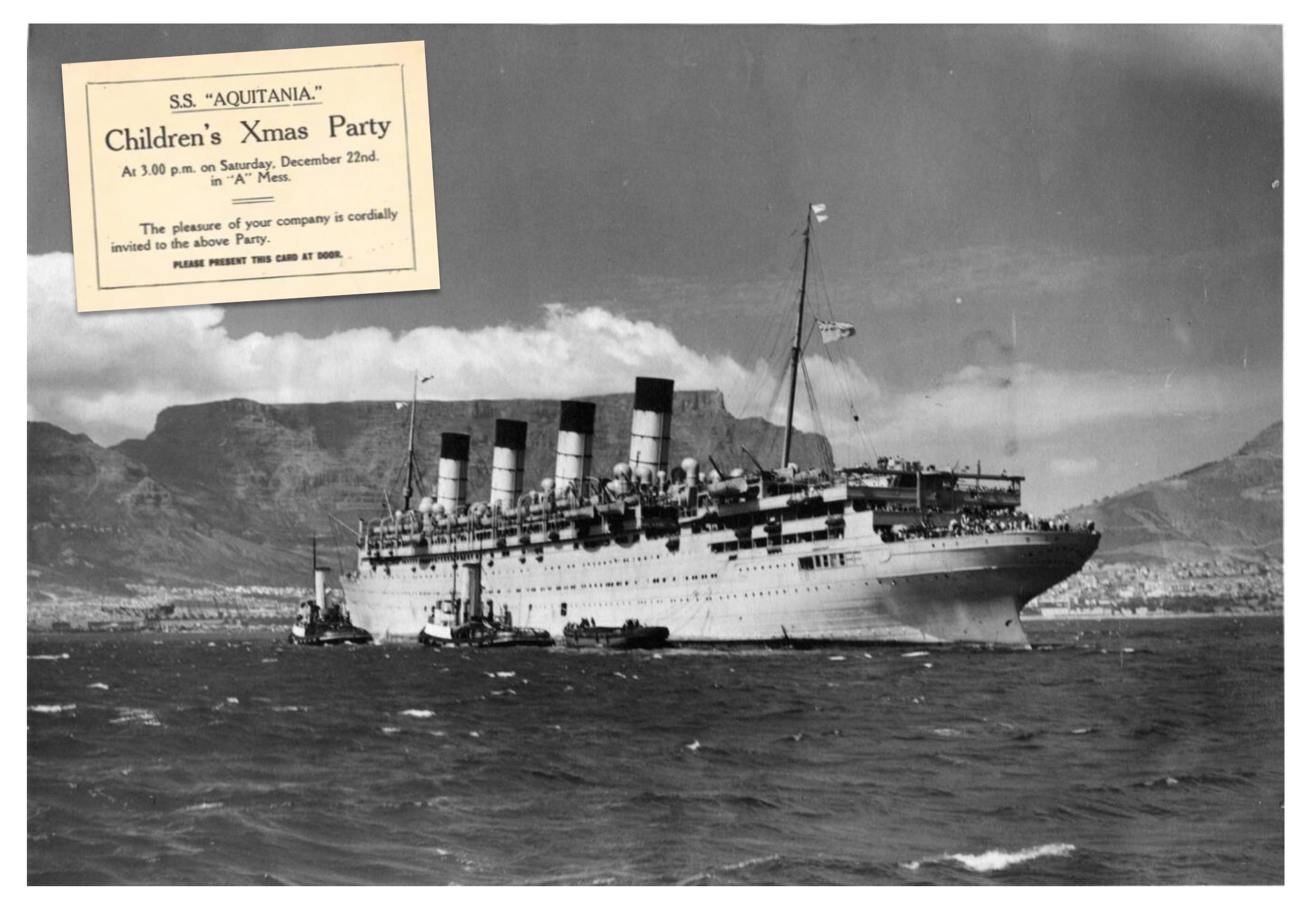

R.M.S. AQUITANIA - story of World's Wonder Ship

110 years ago, at the beginning of the summer of 1914, the R.M.S. AQUITANIA - which later proved to be an ocean liner with probably one of the most interesting careers in maritime history - performed her maiden voyage. This study gives an overview of her unique story.

Introduction:

AQUITANIA was an ocean-going passenger steamship of the British Cunard Steamship Company, which was built after the speed record ships of the company, LUSITANIA and MAURETANIA, as their half-sister (using the experience gained during the design, construction and operation of previous ships). “She was one of the queens of the transatlantic fleet. She was in two wars, a troopship, an armed merchant carrier, a hospital ship, a great transport, a ferry for war brides, and, finally, a ship of hope for displaced persons." praised The New York Times in its issue of December 17, 1949.

Indeed: The AQUITANIA, launched in April 1913 and scrapped in February 1950, left behind an incredible legacy. During its 582 (430 civilian transatlantic) voyages, it sailed more than 3 million miles (5,556,000 kilometers) (of which 500,000 miles, 926,000 kilometers during World War II alone) and carried 1,200,000 people (11,208 passengers in 1914, 90,000 soldiers between 1914-1918, more than 500,000 passengers between 1919-1939, more than 400,000 soldiers between 1939-1945). And her 36-year career almost doubled the average service life of ocean liners built up to that point.

Her owners called her the "Ship Beautiful", passengers called her the "World's Wondership", and her sailors - especially with regard to the ship's war performance - called her the "Old Irrepressible". She owes her fame to several factors:

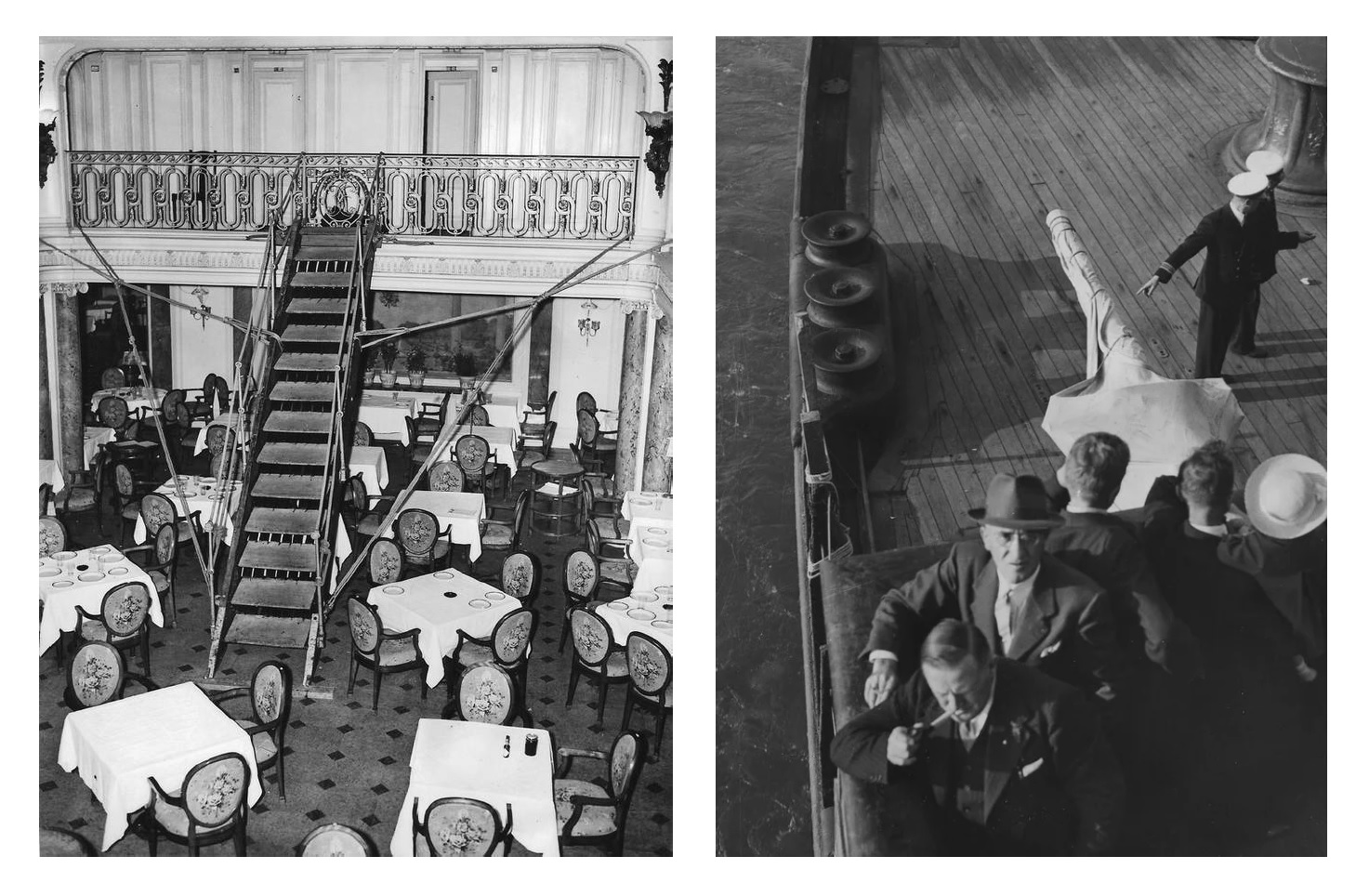

1. Size and elegance: AQUITANIA was one of the largest and most luxurious ocean liners of her time. Due to her large dimensions, spacious interior and elegance, she was a popular ship for transatlantic travelers.

2. Longevity: AQUITANIA has had a long and successful career. She was in active service between 1914 and 1950, so she was one of the longest-serving ocean liners of the 20th century.

3. Versatility: Due to her versatile applicability, AQUITANIA has played various roles during her long career (acting as ocean liner, armed merchant cruiser, troop transport and hospital ship).

4. Popularity: AQUITANIA was a popular ship among passengers due to her comfort, luxury, elegant appearance and amenities, speed and reliability.

5. Survivability: AQUITANIA served in both world wars and – outliving many of her contemporaries – in the 20th century. she operated as a passenger ship until the middle of the 20th century, as the world's last four-funnelled ocean liner

The present study reviews and takes these circumstances into account, and based on them reconstructs the unique history of this great ship.

From the idea to the order:19/04/1902: The American financier and venture capital investor John Pierpont Morgan - after buying 7 large American and European shipping companies between 1886 and 1902 with the aim of monopolizing North Atlantic shipping routes – also makes an official takeover offer to the British Cunard Line, which, however, requests the support of the British government to preserve its independence and exclusively British ownership structure.

30/09/1902: The British government - for which, in the naval arms race initiated by the Germans, it is vital to have a sea transport capacity of sufficient size that can be used at any time in the event of war - enters into an agreement with the Cunard Line, in which, in addition to providing a loan with extremely favorable interest rates and an annual maintenance grant, it commits itself tocover the construction and operating costs of two new speed record ships, in the event that Cunard remains a purely British enterprise and undertakes to place its ships at the disposal of the British government in case of war.

16/06. and 08/08/1904: On the basis of the government-Cunard agreement, the construction of steam-turbine ships LUSITANIA (1906-1915) and MAURETANIA (1906-1935) with a size and speed superior to all previous passenger ships in the world begins. The ships traveling at a speed of 25 knots (46.3 km/h) cross the Atlantic Ocean between Europe and America in 5 days - shorter than ever before.

04/30/1907: The British White Star Line shipping company belonging to the J.P. Morgan empire - Cunard's main British competitor - commissions the Harland and Wolff Shipyard in Belfast to prepare for the construction of three large ocean-going passenger steamships - the OLYMPIC, the TITANIC and GIGANTIC - and to start developing their detailed plans based on the customer's specifications. The White Star Line intends to establish a regular weekly service on the Atlantic Ocean with the three giant steamers that can be departed every 5 days, thus maximizing the financial benefits expected from passenger transport.

23/04/1908: The first public news report in the British daily paper The Daily News that "the White Star Line Company intend to build one or two large vessels to surpass in size any other ship in the world."

16/12/1909: After the laying of the keel of the OLYMPIC (23.04.1908) and the TITANIC (31.03.1909), copying the business plan of the White Star Line, the Cunard Line also decides to build a third running mate next to the LUSITANIA and the MAURETANIA, and entrusts the task of planning to the naval architect Leonard Peskett, who also designed the already completed sister ships.

Fig. 1: Key figures: the great rival American John Pierpont Mogran (1837-1913), George Arbuthnot Burns (1861-1905), 2nd Baron of Inverclyde, chairman of the Cunard Line from 1902-1905, and Leonard Peskett (1861-1924) From 1884 until his death, worked for the Cunard shipping company, and from 1905 he was the chief constructor and designer of the company's most important ocean liners.

Fig. 1: Key figures: the great rival American John Pierpont Mogran (1837-1913), George Arbuthnot Burns (1861-1905), 2nd Baron of Inverclyde, chairman of the Cunard Line from 1902-1905, and Leonard Peskett (1861-1924) From 1884 until his death, worked for the Cunard shipping company, and from 1905 he was the chief constructor and designer of the company's most important ocean liners.The preparation of the concept plan is influenced by several circumstances:

Cunard cannot count on government support for the construction of the new ship, as in the case of LUSITANIA and MAURETANIA, so it has to manage the expected costs from its own revenues. The new ship is therefore designed for more economical operation - more moderate fuel consumption and lower speed - but much larger size and lavish equipment, compared to fast steamers (which could only be operated at a loss without a substantial subsidy from the government). According to Scottish maritime historian John Kurtz Maxton-Graham (1929-2015), therefore called the new ocean liner as the "Cunard's White Star Liner". Indeed: on the decision of Cunard's managing director, Alfred Allan Booth, and the board of directors, the new ship was designed to accommodate 3,500 people (750 first-class, 600 second-class, 2,000 third-class passengers and 900 crew members) and must be designed for average speed of 23 knots (42.5 km /h).

Thus, while the design of LUSITANIA and MAURETANIA was dominated by the German naval threat, the design of the third ship had its roots in the market competition between Cunard Line and White Star Line: White Star Line's OLYMPIC and TITANIC were built 15,000 tons larger than the LUSITANIA and the MAURETANIA, and - despite the fact that the Cunard ships were the fastest - the popularity of the White Star ships grew so quickly during their construction due to the success of the marketing-efforts emphasizing the spacious interior and the luxurious equipment, that there was a reason to worry: when the three ships of the White Star Line enter service, Cunard will be at a competitive disadvantage. That is why the third ship was needed, with which the Cunard Line can also afford to maintain the weekly transatlantic fast service. On the other hand, due to the lack of further British government support, it was decided to focus on the factors that ensure profitable operation in the design of the third ship - i.e. the large size and high luxury, that ensure the sale of more tickets, instead of the high speed that is too expensive. This was a great satisfaction for Cunard, since even the founder of the company, Samuel Cunard, dreamed of a sustainable Liverpool-New York service with three ships in 1838, but - based on the performance of the ships at that time - he could only plan for a two-weekly schedule. Now, however, ships can turn around on a weekly basis.

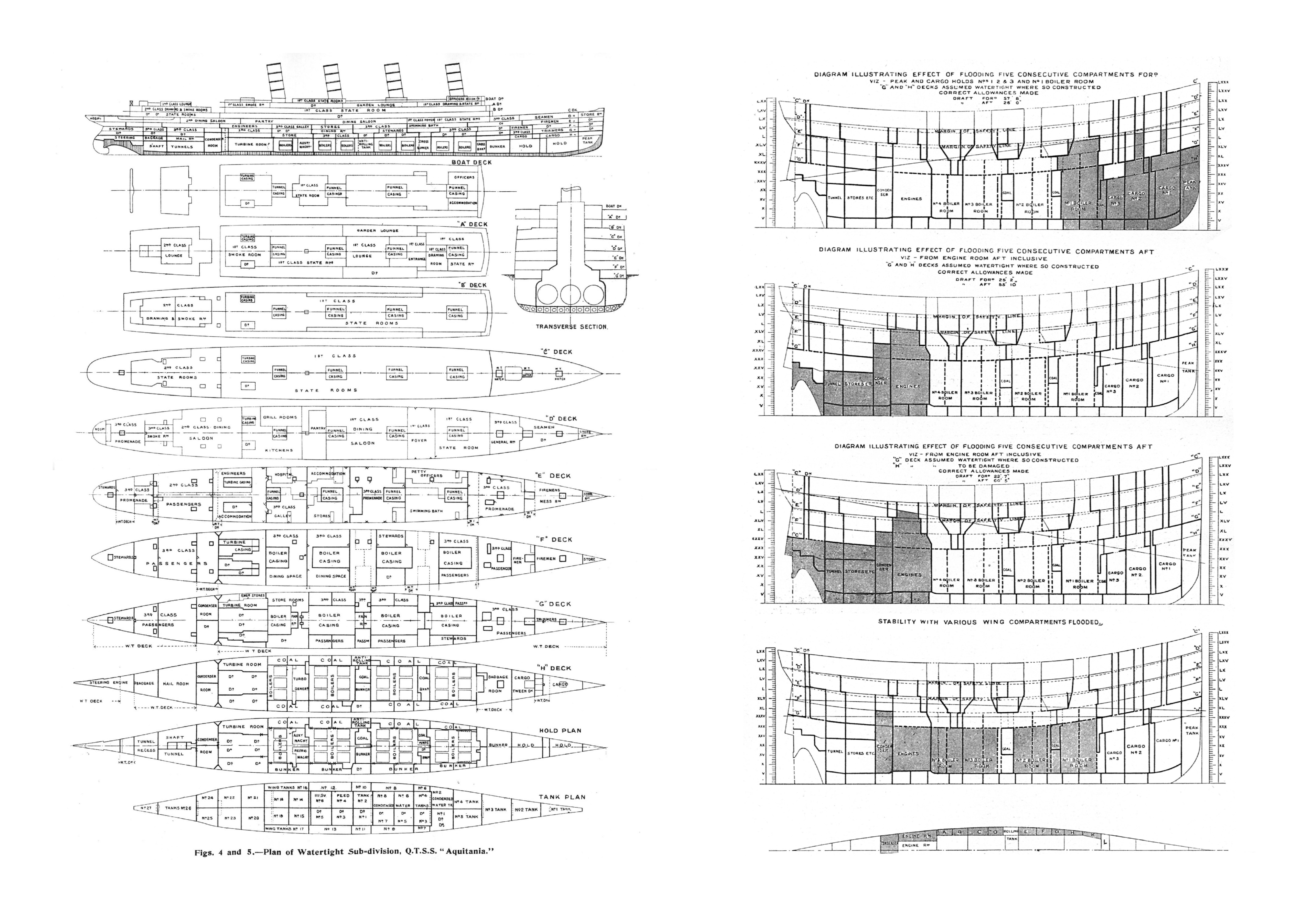

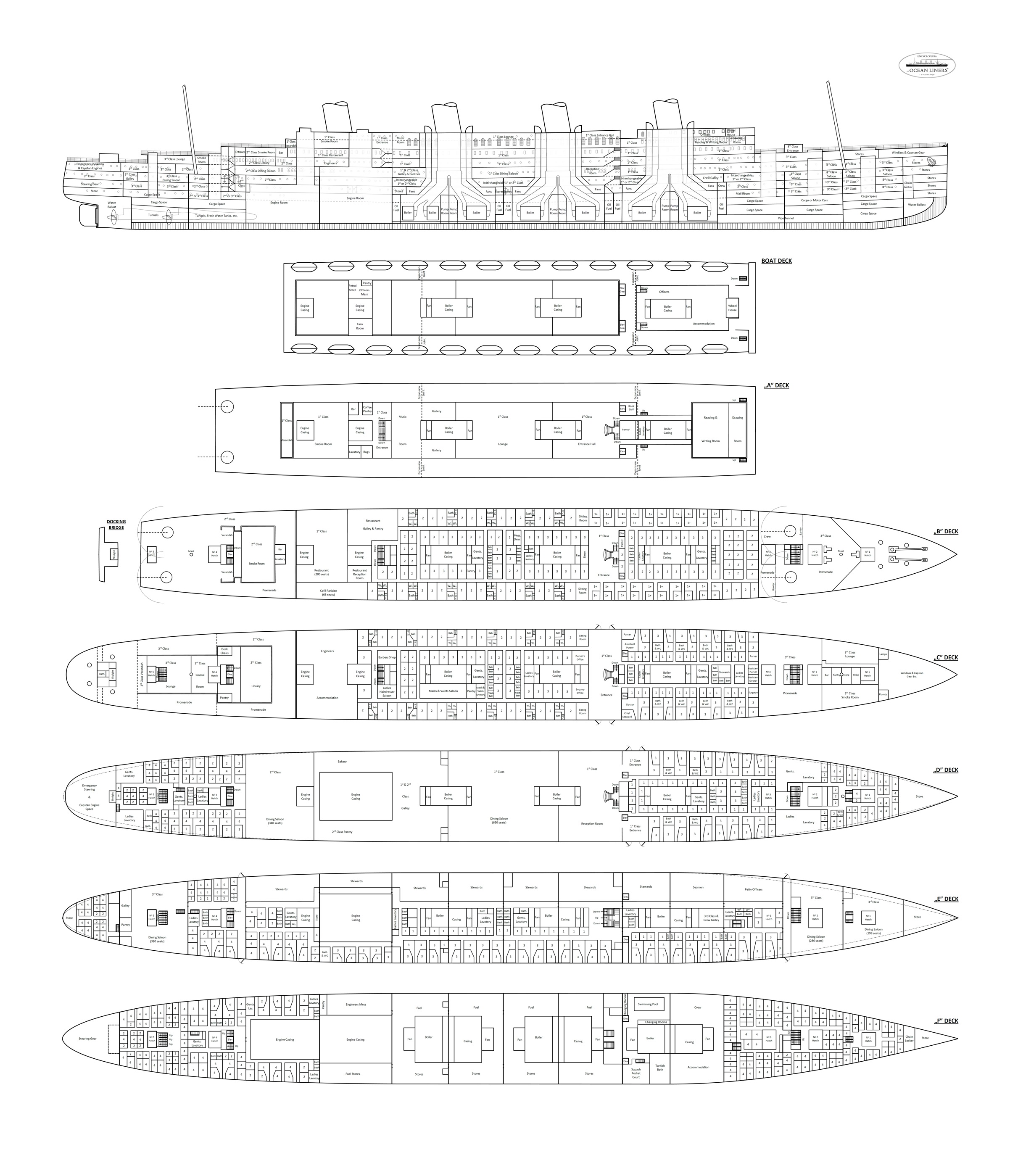

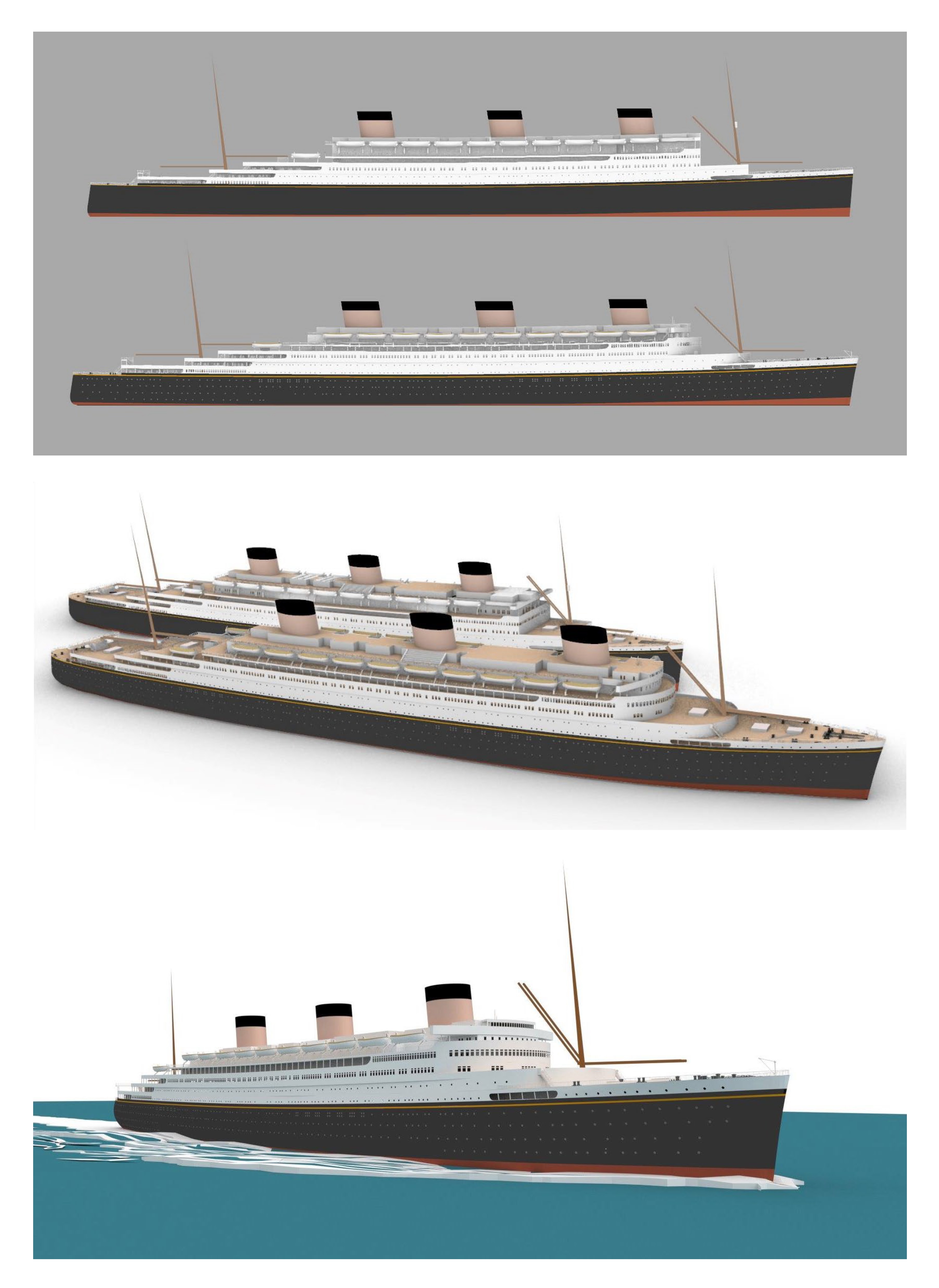

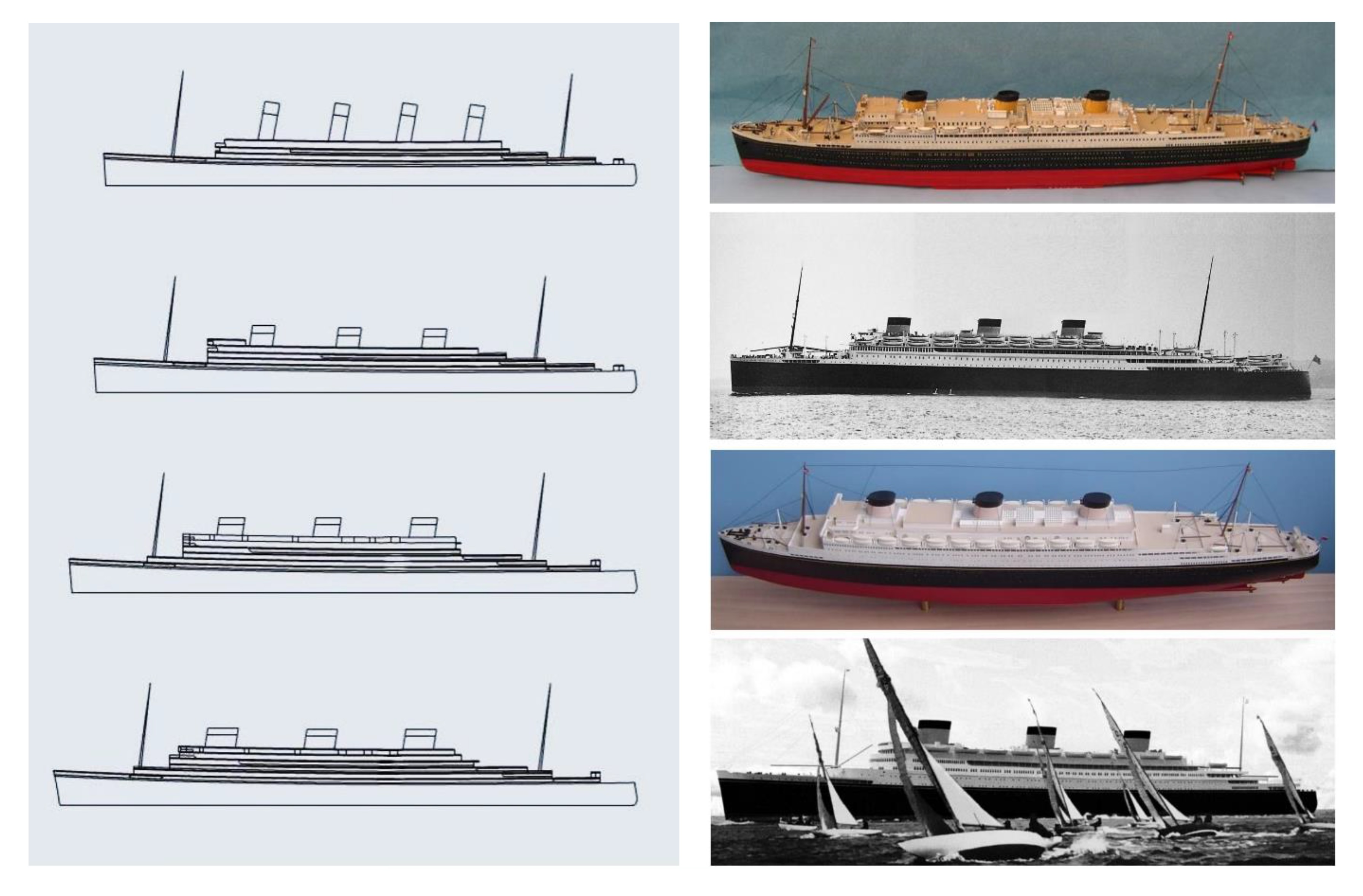

Fig. 2: The rival oceanliner-trios of Cunard Line (top), White Star Line (middle), and Hamburg-America Line (bottom). Although the LUSITANIA and MAURETANIA were 12% faster than the OLYMPIC class, they were also 30% smaller, so if Cunard wanted to be at the forefront in all respects, the AQUITANIA could not be quite the same as her older sisters. But while the British companies were competing with each other, the Germans quietly overtaken them: the size of the IMPERATOR class, built between 1912-1914, exceeded the size of the LUSITANIA by 40%, and that of the OLYMPIC by 13%, and their speed reached 24-26 knots (drawing: Dr. Tamás Balogh © 2024).23/03/1910: Leonard Peskett's first meeting with Lloyd's representatives. Based on the consultation, double bottom built in the full length of the hull with 41 separate watertight compartments for proper trimming and 16 watertight transverse bulkheads spanning the full width of the vessel are proposed, rising 19ft (approx. 6m) above the waterline of the loaded vessel. 6 of these were traversed bylongitudinal bulkheads located 18 feet (5.5 m) inboard from the ship's outer shell to protect the boiler and engine rooms from the sides, and additional transverse bulkheads are proposed to be installed into the spaces between the transverse and longitudinal bulkheads, with 27-33 feet (8-10 m) spacing, so that the resulting spaces serve as longitudinal coal bunkers. Considering the length of the ship, in addition to the longitudinal coal bunkers, transverse coal bunkers can also be placed in front of and behind boiler rooms No. 1, 2 and 3 (the turbo generator is located in the space behind boiler room No. 4).

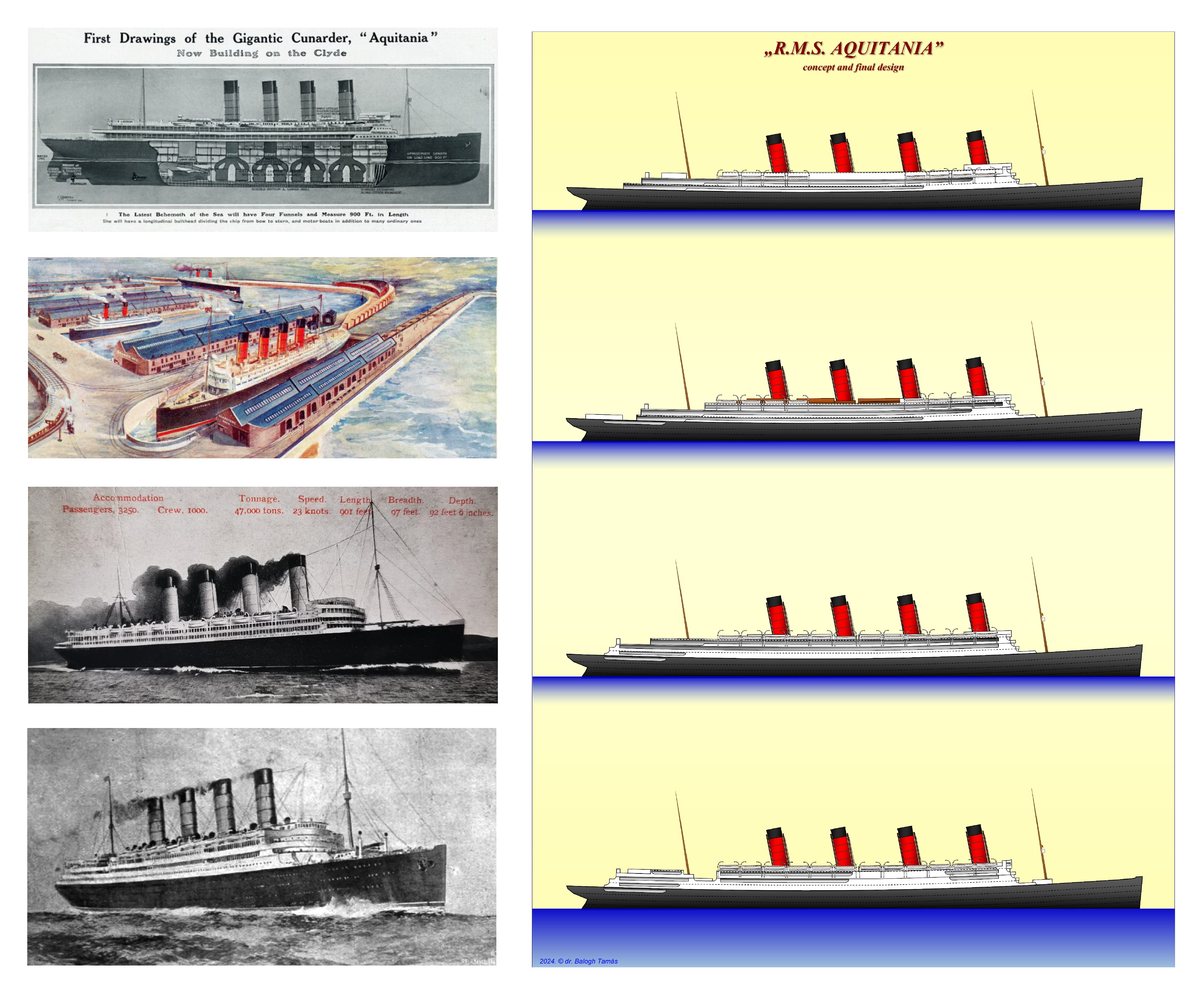

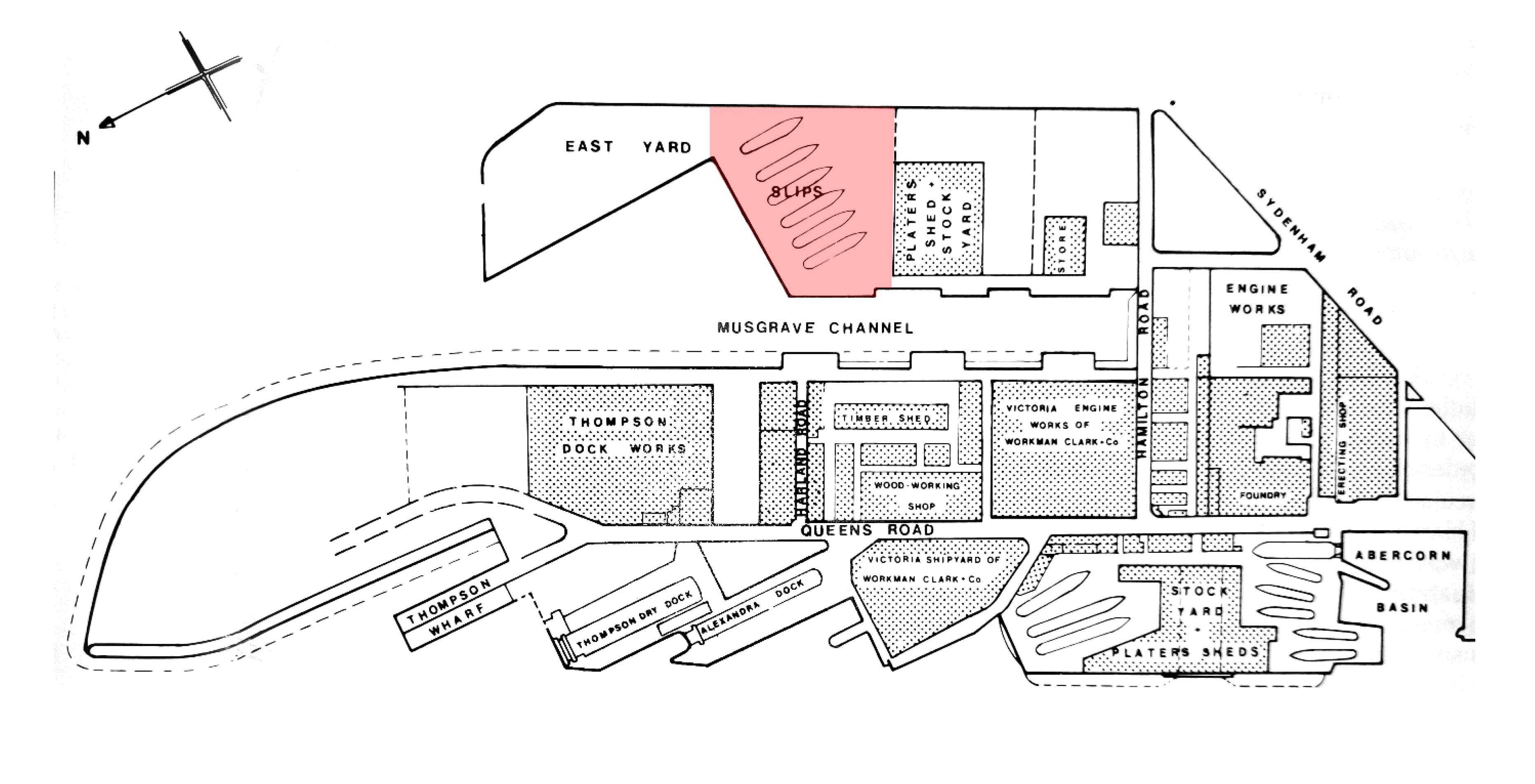

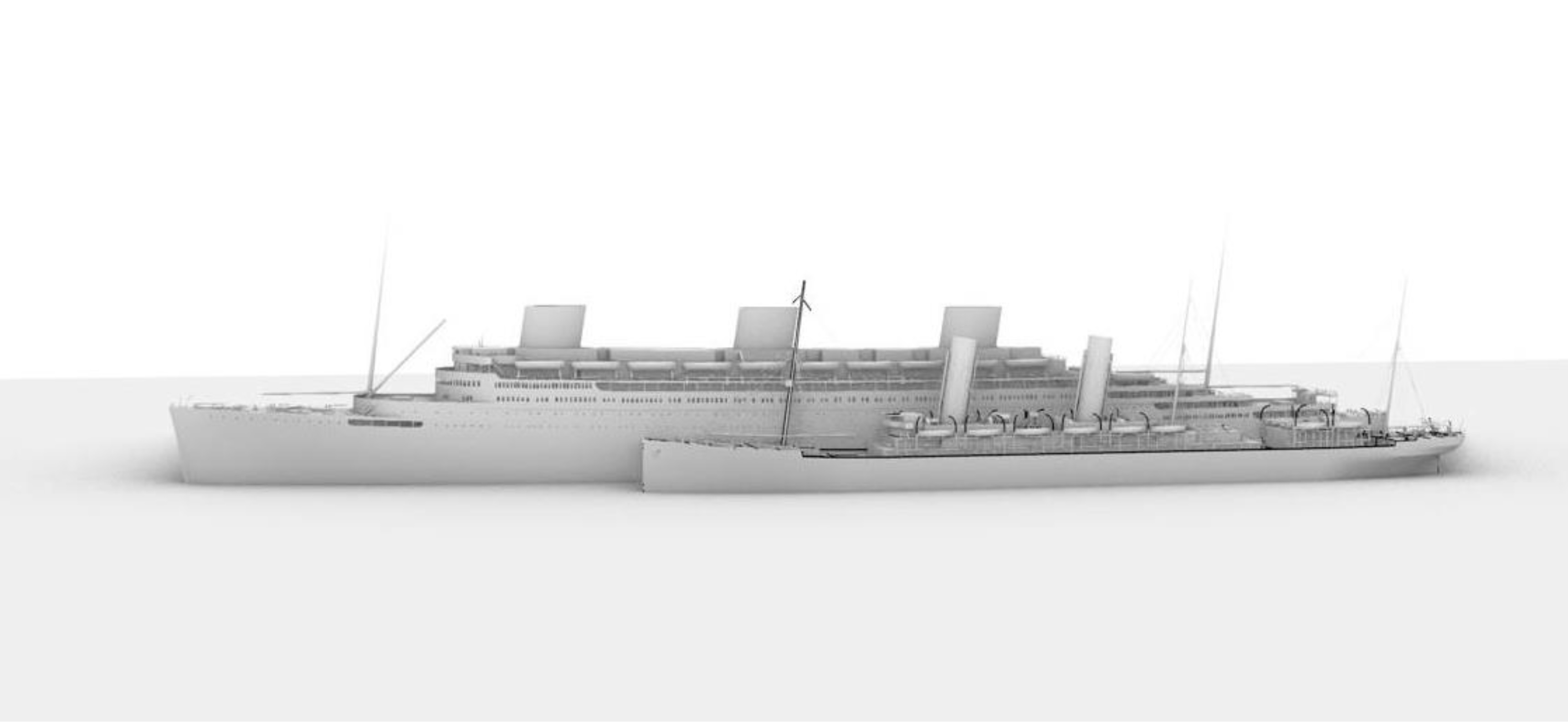

Fig. 3: Development of AQUITANIA plans 1909-1914, using earliest contemporary depictions (left) as basis for the reconstruction (right)(sources here, here, here and here; reconstruction and drawing: Dr. Tamás Balogh © 2024).In parallel with the design, the John Brown Shipyard in Clydebank, which was selected to the construction makes the necessary preparations for building the new ship as follows:

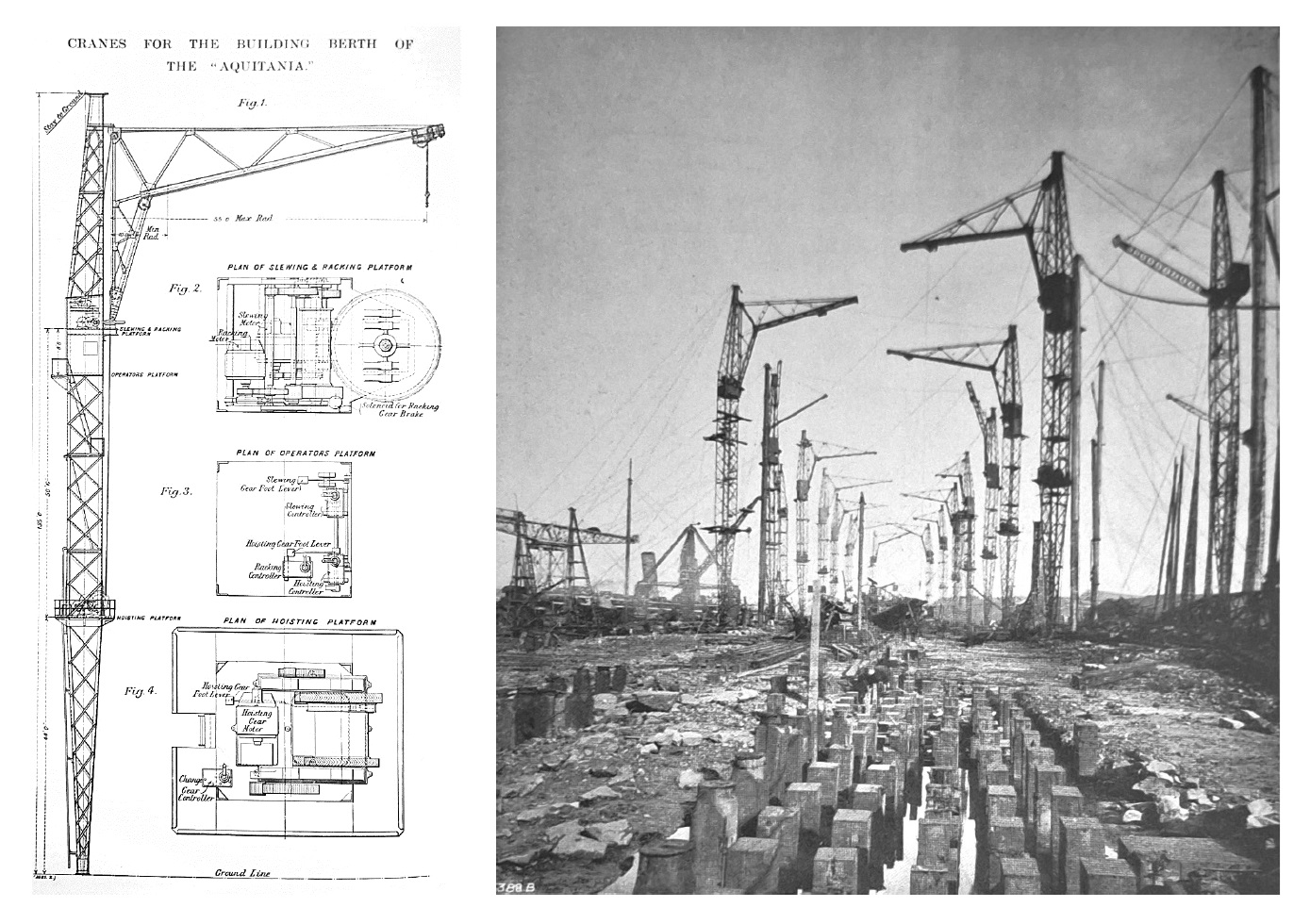

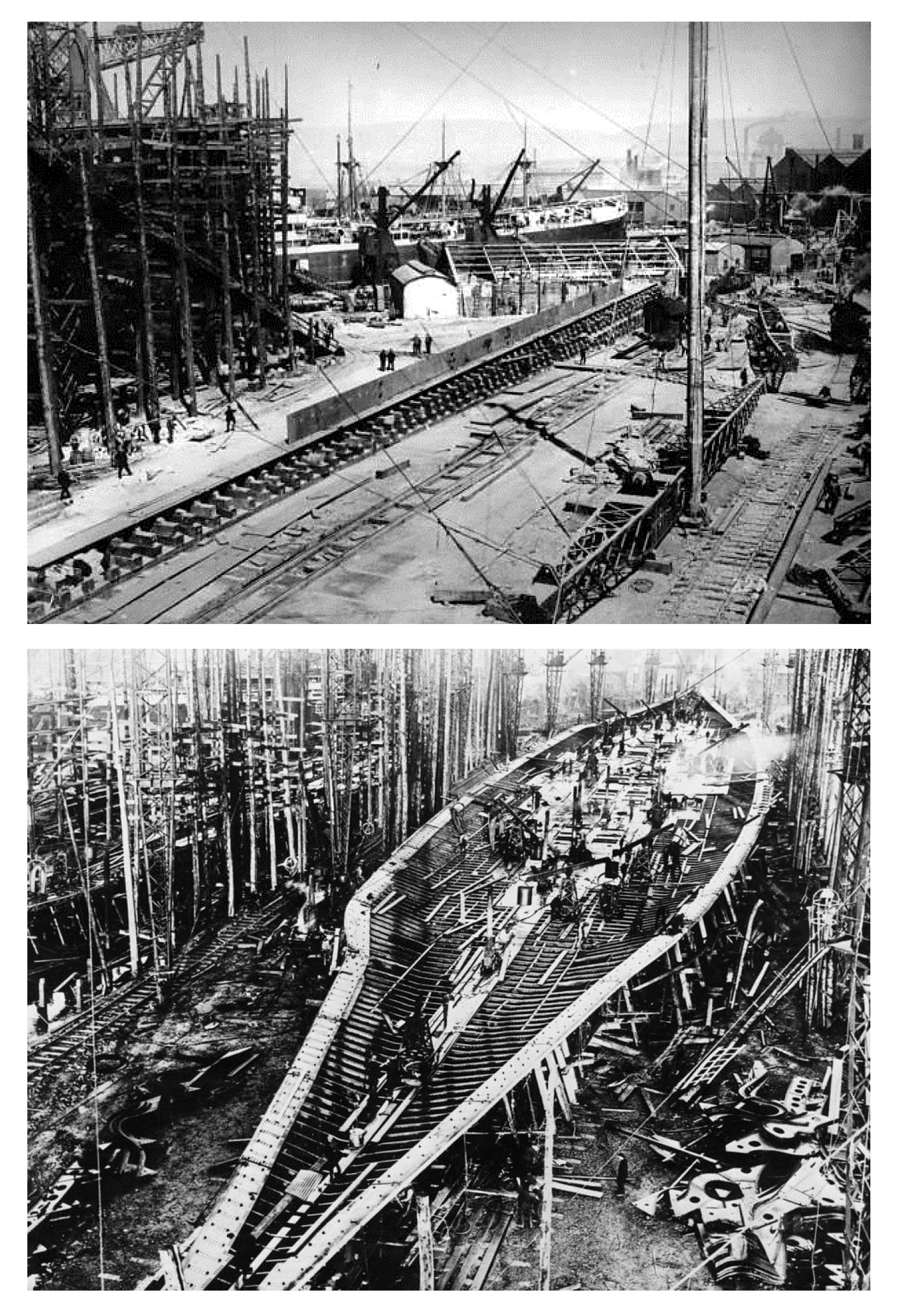

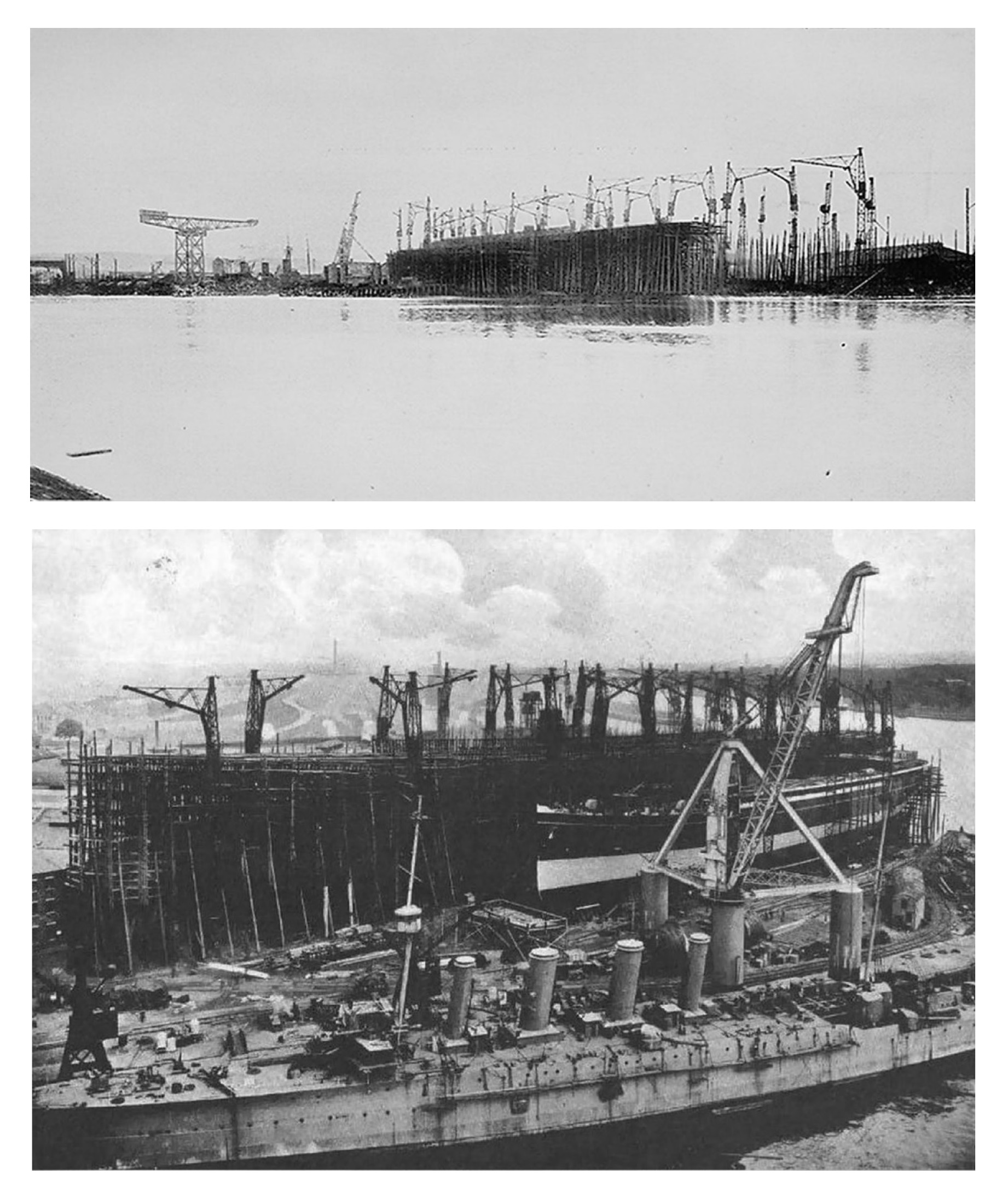

1) As the new ship's large size and weight far exceeds any ship built at the shipyard up to that point, the preparation for construction requires consideration of extraordinary circumstances and measures of a magnitude not previously required on the banks of the River Clyde. The necessary investments will change the image of the entire factory. The slipway space for the construction of the ship (on which the LUSITANIA was also built) receives a special reinforcement - new piling. Steel plates is placed on the cross beams laid on pilings, on which concrete is spread, thus ensuring that the extended slipway cannot sink or become uneven anywhere. The extended and widened slipway area is equipped with a special crane system for lifting heavier building materials.

2) Then, 7 Derrick-type (named after Derrick, London's hangman) column or mast cranes were installed on both sides of the new slipway (their plans are above left), which were designed, produced and delivered by Sir William Arrol and Co. Ltd. of Glasgow (the same company designed a large-scale electric crane system in Belfast for the series production of the OLYMPIC class trio). Due to their great height and jib-extension, these cranes proved to be particularly important during construction. "Their load capacity in the extreme radius of 16.76 m was 5 tons (the smallest extension of the jib was 3.5 m). The total height of the mast was 41.15 m, and the height of the lift was 33.8 m above the berth level. With the help of a slewing gear, the jib could turn at an angle of 205 degrees. The mast was built from rolled-steel sections, well riveted together, provided with a suitable foundation plate and a top plate, to which the guys (tension stiffeners) were attached. The jib consisted of rolled-steel sections and plates, with two rolled-steel channels in the bottom boom, which formed the track for the trolley (which transmitted the load horizontally). The latter was constructed of steel plates and mounted on four single-flange wheels, and moved by a four-part rope, which was wound around a cast-iron drum driven by an electric motor. Suitable stairs and platforms are provided to give access to all parts requiring attention. The driver's cabin is situated immediately under the slewing gear, where the man has complete control of the operations and a clear view. The motors are of the totally-enclosed reversing type, especially designed for crane service in such a way that their operating temperature did not rise above the temperature of the surrounding atmosphere at 32 degrees Celsius even after half an hour of running at full load. The motors were equipped with a tramway-type reversing controller, having the vertical contact barrel mounted on ball-bearings to ensure ease of operation. The jib-slewing motor drives a spur-wheel, attached to the jib foot-bearing through reductions of gearing. The load is lifted on a single-part best plough-steel wire rope, winding on to a cast-iron drum, driven by a motor, through the medium of three reductions of spur-gearing. A double set of gear is provided for the last reduction in order that the two specified speeds of hoisting may be obtained. Change of gear is effected by means of a claw-clutch. The hoisting-drum is of large diameter, turned and grooved to take the full amount of rope in a single lap. Two breakes are provided: one is an automatic electric brake, operated by a means of a solenoid magnet connectedin such a manner that the brake is released directly the motor is started, and is applied directly the current is cut off, or fails for any reason. A foot-brake is fitted on the hoisting-motor spinfdle, so that the event of failure of the solemnoid brake, this brake may be applied by the opartator. The speeds of working are: Hoisting: 18.3 m/min for a 5 ton weight, 30.5 m/min for a 3 ton weight. Racking: 10.7 m/min for a weight of 5 tons. Slewing: 200 degrees/min for a weight of 5 tons." AQUITANIA's hull grew larger and larger with the help of these cranes on the slipway.

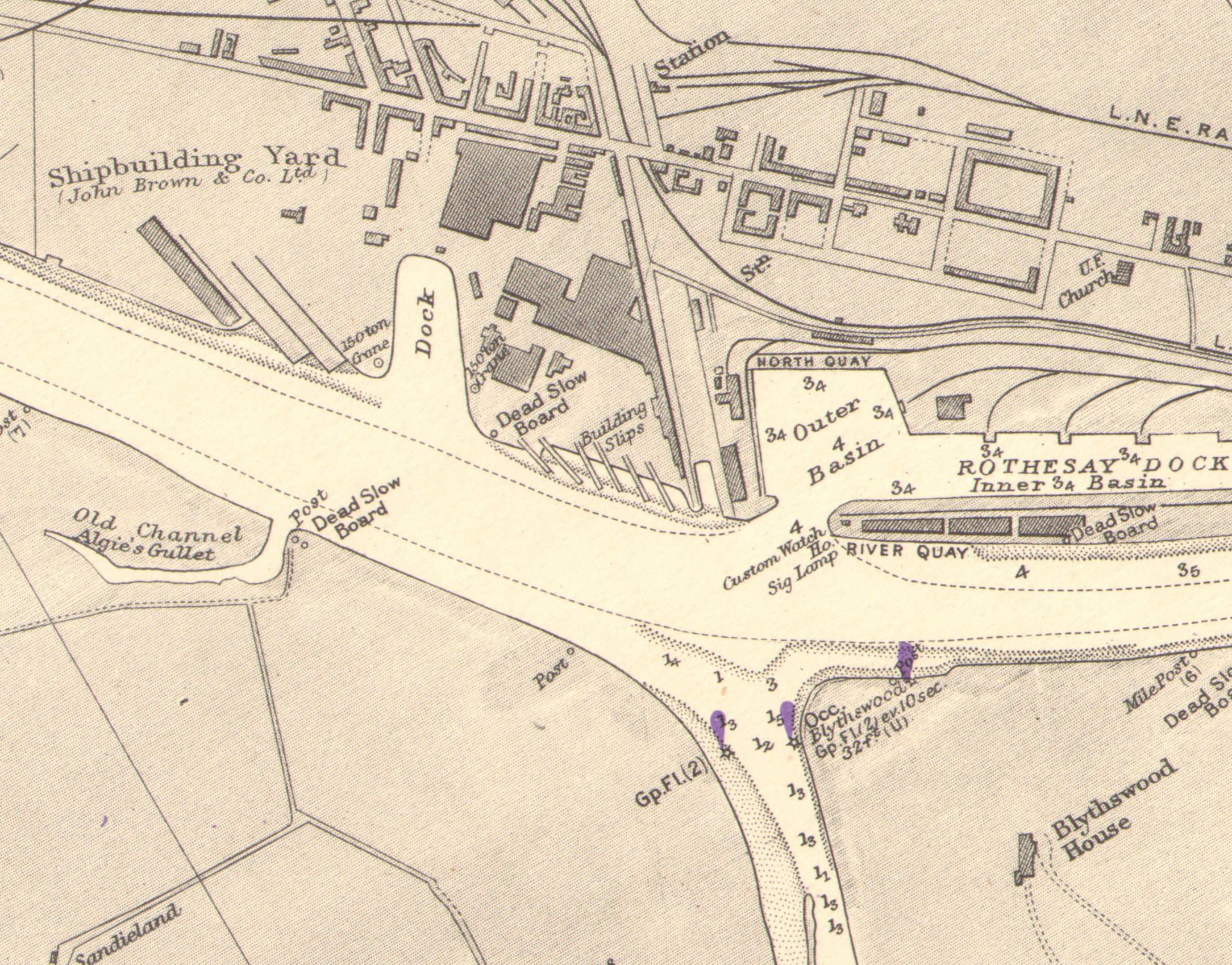

Fig. 4: The John Brown Shipyard in Clydebank in West Dunbartonshire (on the map, the ocean is on the left, and the city of Glasgow is on the right). A significant development in the shipyard was necessary to start construction. To the east of the fitting out basin ("Dock"), which divided the site, there were six old slipways, on which all the large ships were built, while the new slipways to the west of the Dock were used for construction of lightcruisers, canal steamers and other similar smaller vessels. In order to lay the keel of the AQUITANIA with minimal intervention, the areas occupied by two previous slipways were combined, so that five of the six slipways remained. At the same time, the service buildings at the front of the two former slipways (which housed the ship design and painting departments) were demolished, but the sheet metal, assembly and machine tool workshops continued to operate at the head of the rearranged slipways. The organization of the shipyard is praised by the fact that the AQUITANIA, largest British merchant ship up to that time, the HMS TIGER, the largest British battlecruiser, and the HMS BARHAM, the newest QUEEN ELIZABETH-class battleship, were built at the same time in the rearranged slipways. These were uniformly directed to the mouth of the River Cart, a left bank tributary of the River Clyde, as ships longer than the width of the Clyde could only be launched if they were admitted into the River Cart.

Fig. 5. and 6.: The new Derrick-type cranes (left) and foundation for the new slipway (right). As AQUITANIA's keel formed a sharper angle with the River Clyde than LUSITANIA's, new piling was required, particularly at the lower end of the slipway area, to secure the hull at the moment when the cradle supporting the ship's stern leaves the slipway and the stern of the ship is already held by the water. Based on experience in launching long ships, careful calculations were made to determine the moment at which the stern begins to float and the point at which the weight of the moving hull exerts a downward pressure on the slipway. Accordingly, piles were placed close to each other under the keel blocks supporting the keel and the area occupied by the slipway area, which were fixed with heavy stone scattering and finally concreted all around (source for both pictures: here).

Figs. 7. and 8.: Above: AQUITANIA's keel layed down. Below: the finished double bottom. (Source: here and here.)06/05/1910: The keel-laying of the new ship at the John Brown Shipyard, Clyde Bank with yard number 409.

10/09/1910: The Cunard Line writes a letter to the John Brown Shipyard about "General conditions of the Proposed new Steamer. The hull, outfit, equipment, engines, boilers, auxiliary machinery, etc. are to be constructed of the very best materials, finished complete in a first-class style of workmanship to the entire satisfaction of the Owners, without any charge owing the contract price, unless previously agreed in writing."

08/12/1910: Official order of the ship (six months after the start of construction). By this time, the framing of AQUITANIA was nearly completely finished.

Fig. 9. and 10.: AQUITANIA's hull is completely framed in the background. In the foreground is the cruiser HMS SOUTHAMPTON under fitting out. On slipway betwen the cruiser and the oceanliner is the passenger steamship RMS NIAGARA, nearing her completition. The presence of the two other ships dates the picture between to May 1911 and August 1912. (source: here and here).

From construction to the handover:10/02/1911: Official announcement of the new ship's name in the press: "The Cunard Company has decided to name the new 50,000-ton vessel which is now building for it at Clyde Bank the Aquitania."

10/05/1911: Finalization of the steel structural plans for the new ship.

14/06/1911: The inaugural voyage of the OLYMPIC. 8 days earlier in the paper Liverpool Journal of Commerce, the first guess appears, and 2 days later the official announcement is published in The Shipping Gazette and in the Lloyd's List that a third ship is being built next to the OLYMPIC and the TITANIC.

26/08/1911: Since Cunard wants an ocean liner capable of surpassing the OLYMPIC, which is considered to be its main rival - of huge size and lavishly decorated spacious interior - Leonard Peskett, Cunard's chief designer, goes on a study-tour on OLYMPIC as one of the passengers of the ship's third voyage, and returns home to submit his report about his experiences. His observations range from the ship's main dimensions, load capacity, general arrangement and propulsion to the smallest details of the equipment.

Regarding the vessel's draft conditions, for example, he states: “The center of the disc is 34 feet 0 inch above the bottom of the keel: The load line was, therefore, submerged 17 inches, allowing the density of the water to be 1020 kg/m3 the draft would be about 15 inches too much.".

Among the passenger comfort services, he was impressed by the spacious spaces: "One cannot help being impressed - even with a large number of passengers on board - with the superabundance of promenade deck space."

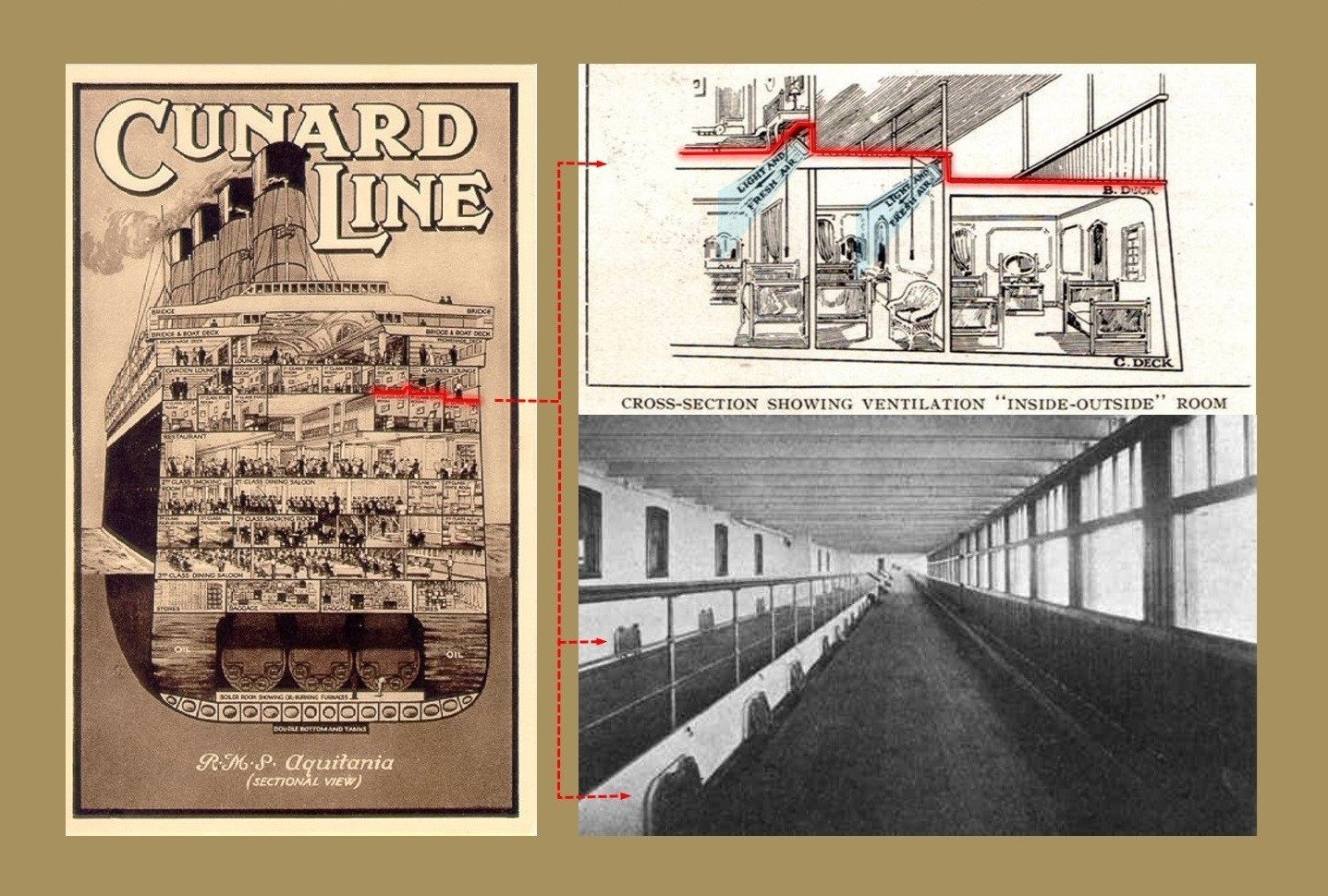

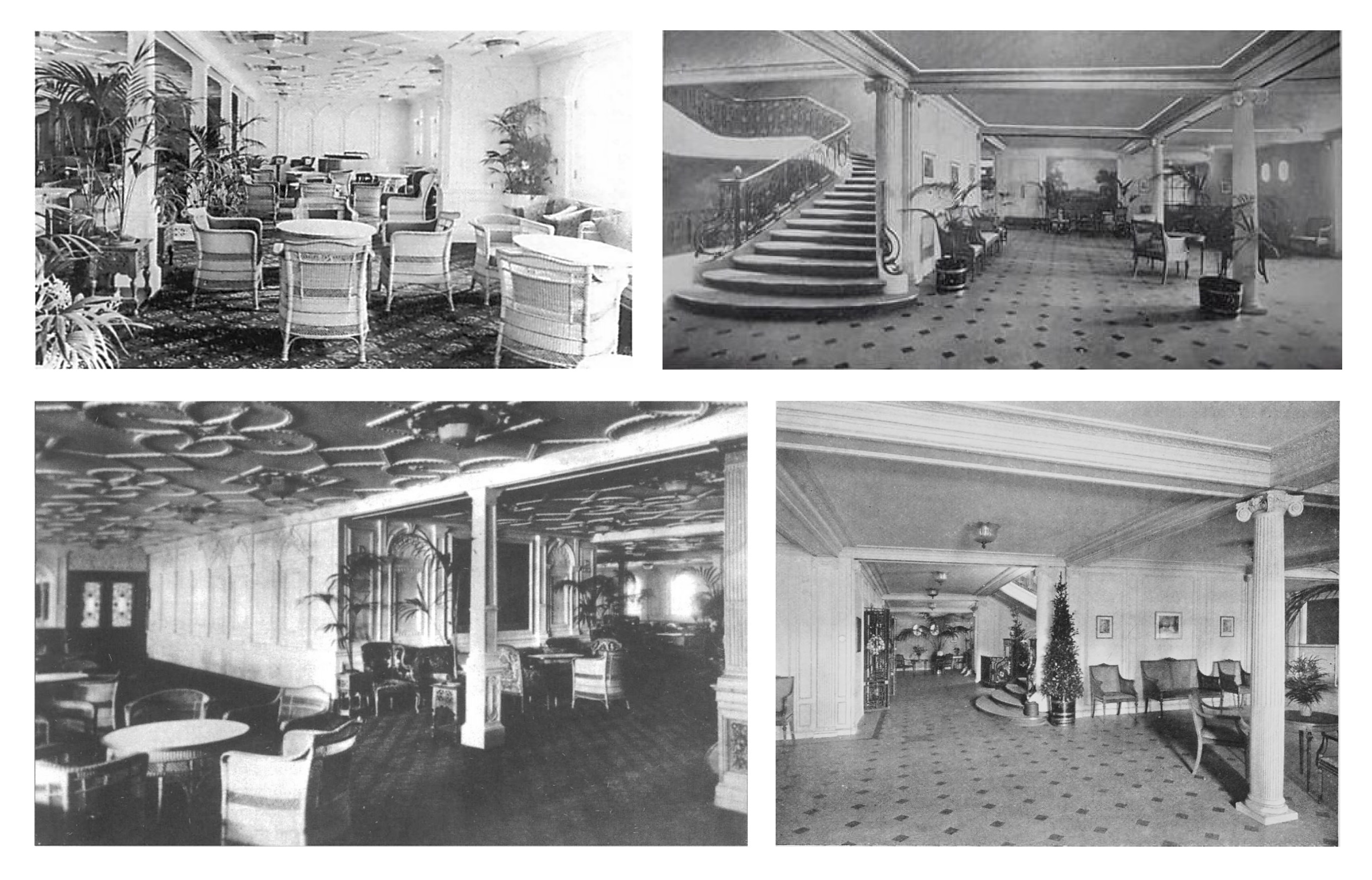

Figs. 11, 12. and 13.: Based on the experience gained at OLYMPIC, Peskett designed a two-level promenade for the AQUITANIA "B" deck, more spacious than ever before. This not only satisfied all the needs of passengers using the promenade deck (the raised upper section was reserved for deck chairs, the lower section was reserved for those who would like to promenading), but secure natural light and fresh air for the internal cabins (on deck "C", without direct access to the sea) at the same time. In this way, Peskett created a type of "inside-outside" cabins that was not known until then, which further enhanced the magnificence of AQUITANIA compared to other ships.Peskett also noticed which room is the most visited: "The reception room serves as a meeting place before ans as a lounge after meals. The band plays here after lunch at afternoon tea and after dinner, the room is full, but after dinner the lace is crowded all the surplus chairs an settees have been moved out of the en suite rooms and placed there. Chairs are brought out of the saloon, and every available space - main stairway included - is occupied by passengers as ceases (21:15) they disperse to their cabins and to the promenade and public rooms on "A" deck. There seems to be no doubt that if the band played in the reception-room until 23:00 o'clock the passengers would remain there, as only those who could not secure seats had moved away until the music had ceased."

He also recorded the schedule of the band: "10-11 AM, band plays in 2nd class companion. 11-12 do 1st, boat deck companion, 5-6 do 2nd class companion, 8-9.15 do reception room, 9.15-10.15 do 2nd class companion."

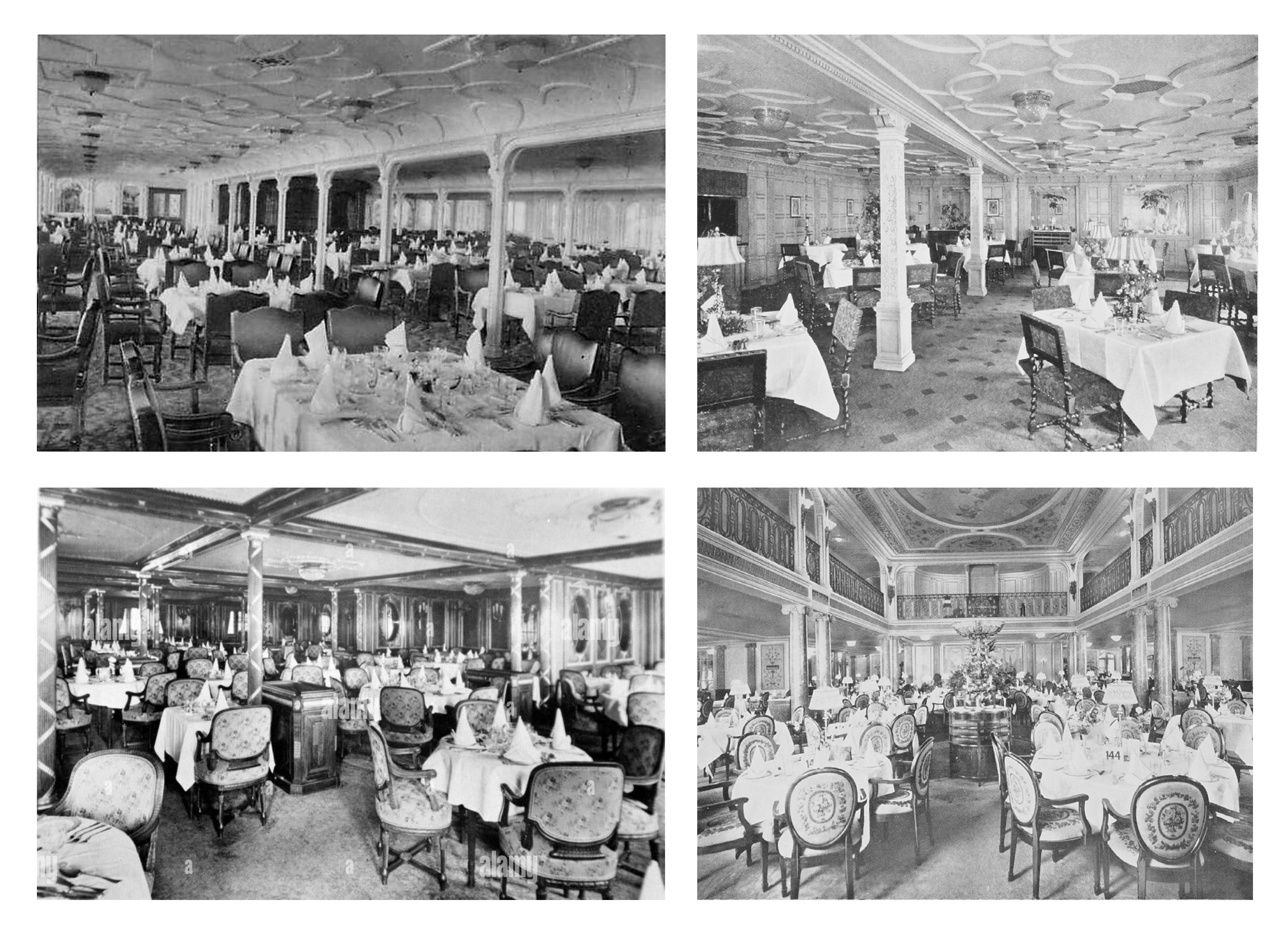

Figs. 14.-15. and 16.-17.: The first-class lounge aboard OLYMPIC (left) and AQUITANIA (right) looking towards the bow (above) and looking from the starboard side to the port (below).He paid special attention to the a la carte restaurant: "The restaurant is run by the owners, under the superintendence of a manager, the department is entirely separate from that of the chief steward, having an independent staff, galleym strore-rooms, etc. Owing to the great demand fro seats in the restaurant the tables have been increased from 25 to 41 (merely providing 33 additional seats), the introduction of the restaurant appears to be creating a new class. The restaurant certainly finds a place for that class of passenger who is always dissatisfied with the catering on every ship in which he may travel. The question, however, is whether, after having to pay a restaurant account for one voyage, he will not be more content to take, without demeur, his food in the saloon passage money for taking meals in the restaurant is stated to be £5. Judging from reports, this amount would scarcely suffice for one day's patronage. An objection to the restaurant is that the windows open out onto the 2nd class promenade."

In the first-class dining room, he made the following observations: „As regards the planning and general seating arrangements, very little fault can be found. It is in the ventillation of the room that an apparent error of judgement has been made. There is no operating or well in the centre. At first, there was no provision made for exhausting the vitiated air from the saloon, but while the ship was in southampton two small fans were fitted over gratings in the ceiling in a position about midway between the machinery casings and some 16 feet out from the middle line. Ordinary fans have also been fitted in all convenient positions, owing to the great beam and the difficulty at thet depth of providing natural light. […]The inner part of the window is made up of leaded glass. When these windows are closed one cannot detect the outline of the ports the light being well diffused over the whole surface of the inner glass. Inside the window and on each side of the frame theres is a strip of linolite fitted which proves vry effective at night. […] A number of restaurant menus are attached upon which are given the prices for the various dishes. The minimum rate per head for a dinner for three or more persons is 12 shilling 6 pennies. In the matter of time occupied in the execution of passengers' orders, nothing better could be desired. The two sides of the saloon are separately served, i.e. the port side is served from the port pantry, and the starboard side from the starboard pantry. At luncheon and dinner, port is served from tureins pleased on sidetrarts in the saloon. Regarding the standard of quality, method of serving the food, napery, cutlery and general service, the is much higher in the Cunard then in White Star - an opinion expressed several times by passengers on the OLYMPIC who have evidently travelled by both liners. It was noted that all saloon stewards uniforms has light blue facings, while those employed elswhere wore the ordinary uniform without anydistinctive markings. The 1st and 2nd class galleys and pantries appeared to give satisfaction to all concerned. The galleys are warm in the neighbourhood of the ranges.”

Figs. 18.-19. and 20.-21.: The first-class dining room and the a la carte restaurant on OLYMPIC (above and below left), and the first-class dining room and grill restaurant on board AQUITANIA (above and below right).Regarding the fourth dummy-funnel, which contributes the most to the famously elegant, balanced profile of the OLYMPIC-class, Peskett noted that: „The dummy funnel from which so much in the way of ventilation was expected has not proved a success. There are so many currents of air being driven in at the bottom of the funnel which are colder than that in the compartments below, that an air-lock is formed at that particular place, and the heat on the top platforms of the reciprocating engine room and between the top of the turbine and bottom of the funnel is excessive. The theory of the cool air coming down the engine hatch and the hot air going up the dummy funnel seems feasible, but in then case it does not work, as ado sated, to the colder air from other compartments being exhausted into the base of the funnel. The writer went to the top of the funnel, but could feel no great rush-of air going out. The whole of the inside of the funnel was at a moderate temperature, and there was nothing to indicate that the funnel was exhausting hot air from the machinery spaces. The air from all lavatories and pantries is exhausted by powerful fans, the inlet of fresh air being by the entrances to the lavatories and by side ports only. All first, second and third-class public rooms also second class, third class and crew's quarters, are heated and ventils by the thermotank system.”

He also examined the Turkish bath with an expert eye: „The turkish bath is open to ldies at various hours as advertised a charge of 4 pennies (which includes the use of swimming bath) is made, the bath, as far as fittings, ventilation, and hot-air supply are concerned, is not a success. In the steam and hot rooms the sides are covered with "emdeca", the enamel on which is all peeling off and the zinc going to powder (samples taken from walls submitted). The cooling room os stuffy and needs more fans to exhaust the vitiated air, altogether a considerable alteration is required.”.

Regarding the other sports facilities available on board, he noted: „The gymnasium was fairly well patronized, and seemed at no time to be unoccupied, but it is too far away from the swimming bath, raquet court, etc.”

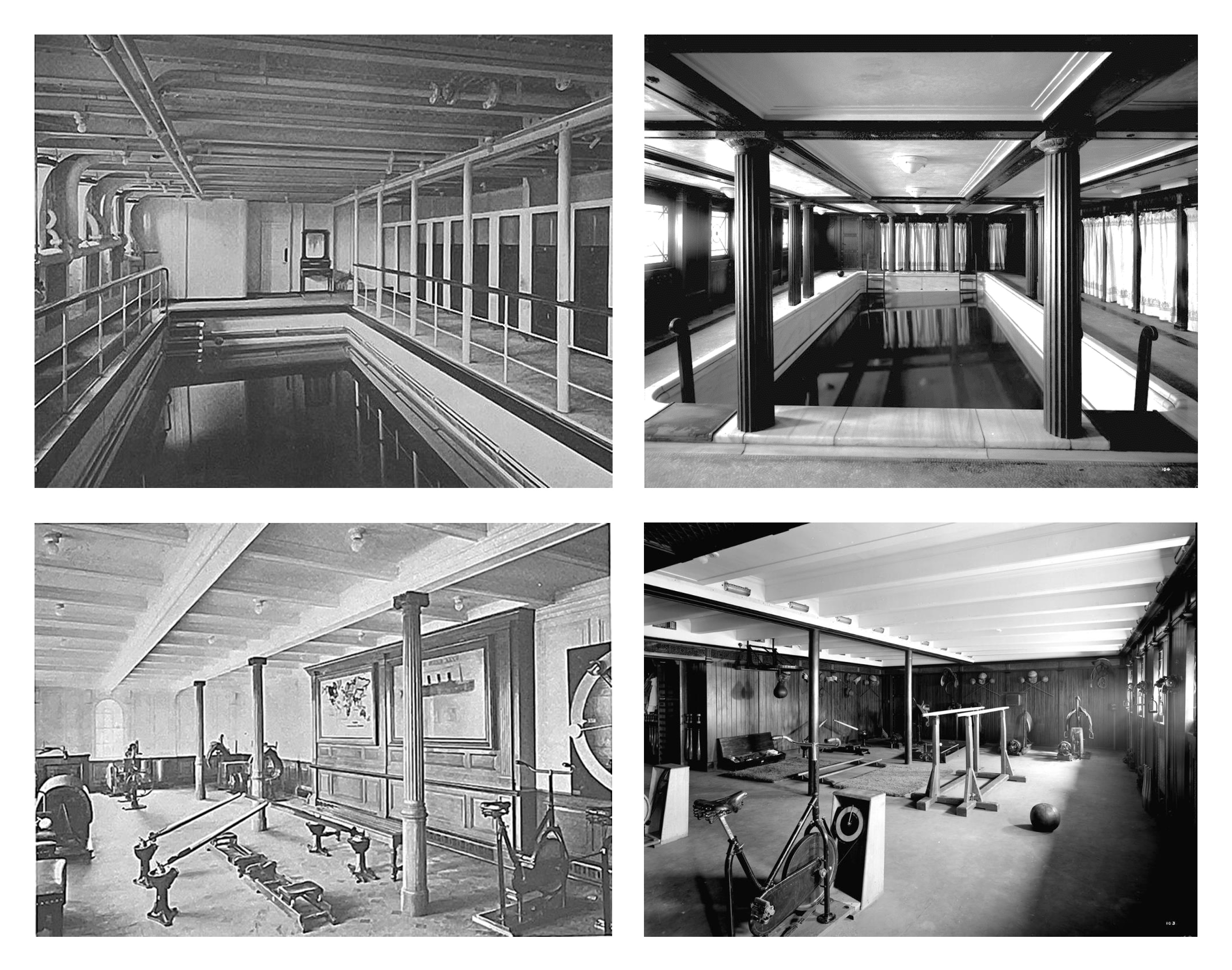

Figs. 22.-23. and 24.-25.: Swimming pool and gym on board OLYMPIC (left) and AQUITANIA (right).In the case of the AQUITANIA, Peskett tries to overcome the deficiencies experienced on the OLYMPIC by incorporating those innovative solutions tested on board FRANCONIA and LACONIA, (Cunard's medium-sized experimental ocean liners built in 1911-1912) into the ship's passenger-comfort services - namely (1) the shipboard-gym used for the first time by the company, (2) the bathrooms with running water introduced in the first-class suites (instead of the previous wash stands equipped with fall-front ceramic wash basins, hiden behind cabinet doors), (3) the movable chairs used in the first-class dining room (instead of the swivel chairs bolted to the floor before), and (4) all of these novelties are also planned for the second-class restaurant at AQUITANIA. Furthermore in order to moderate the AQUITANIA's rolling and to prevent inconveniences experienced in the swimming pool of the OLYMPIC, both caused by the characteristic movements of large ships in strong sea waves (heaveing, swaying, surgeing, rolling, pitching and yawing), it is decided to use of U-shaped anti-rolling tanks, recently developed by the German Hermann Frahm (patented July 15, 1908).

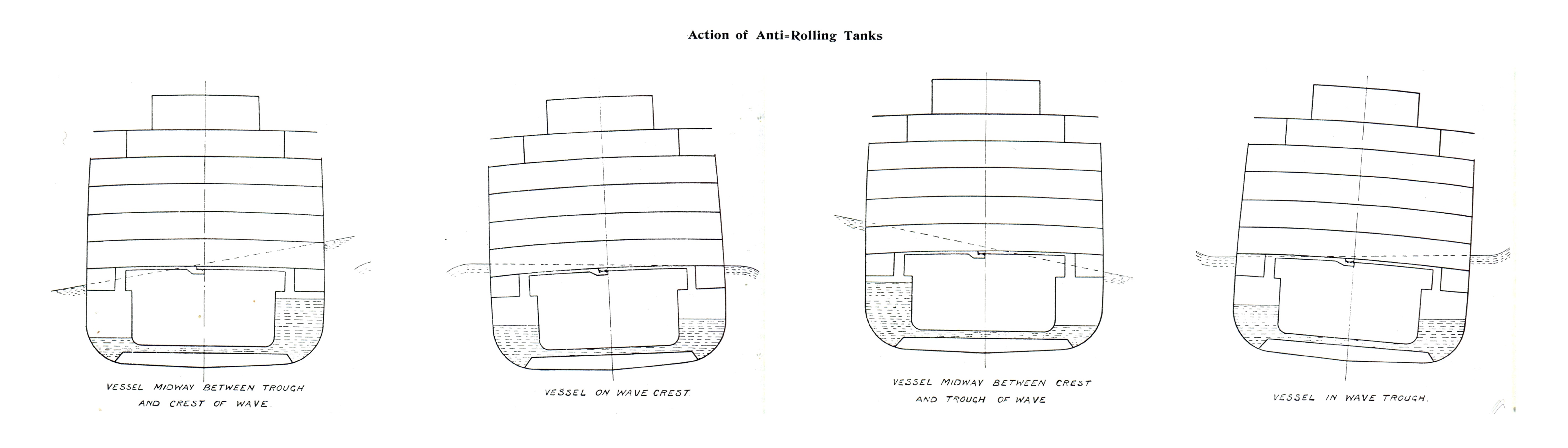

The invention was developed to reduce the considerable rolling of the German steamer YPIRANGA (built in 1908) by the German inventor Hermann Frahm, who suggested to install onboard a tank, having two lateral reservoirs connected at the bottom by a water duct, and at the top by an air duct. In some later designs the air duct was removed and the tanks vented to atmosphere. The water oscillation in each reservoir could be controlled by the air pressure, thus giving rise to the anti-roll U-type tanks steamers YPIRANGA and CORCOVADO and gained significant roll reduction by using tanks having a mass of 1.3 to 1.5 % of the ships displacement. He noted that the best location to place the tanks is above the center of gravity of the ship, located one on port and. one on starboard. The principle of operation of anti-roll tanks is that as the ship rolls, the fluid inside the tank moves with the same period the ship moves, but lagging a quarter of the period of the rolling of the vessel weight of the mass of fluid produces a moment that opposes the roll motion. This moment attains its maximum values when the ship passes through its vertical position.

Fig. 26.: Illustrative drawing of the operating principle of the Frahm anti-rolling system (source).Although Peskett studied the OLYMPIC, he ultimately did not follow her proportional appearance created by her designer - Alexander Carlisle (although both ships were built with 9-9 passenger decks), and instead of to follow the use of split superstructure of the OLYMPIC (consisting of a raised forecaslte and poop deck and a higher middle superstructure between them), he takes over and develops further the design of the sisterships LUSITANIA/MAURETANIA, as well as the CARMANIA/CARONIA and FRANCONIA/LACONIA. The lack of a raised forecastle deck made the main superstructure in the middle appear taller. Therefore, and due to the usual design of all Cunarders, (i.e. the superstructure covers most of the entire length of the deck - this is the so-called "full-superstructure"), the main and only superstructure remains large compared to the hull, with a "boxy" appearance, and this cannot be mitigated even by tilting the funnels and masts at 9 degrees.

30/11/1911: Laying of the keel of the third OLYMPIC-class ocean liner, the GIGANTIC, now called BRITANNIC.

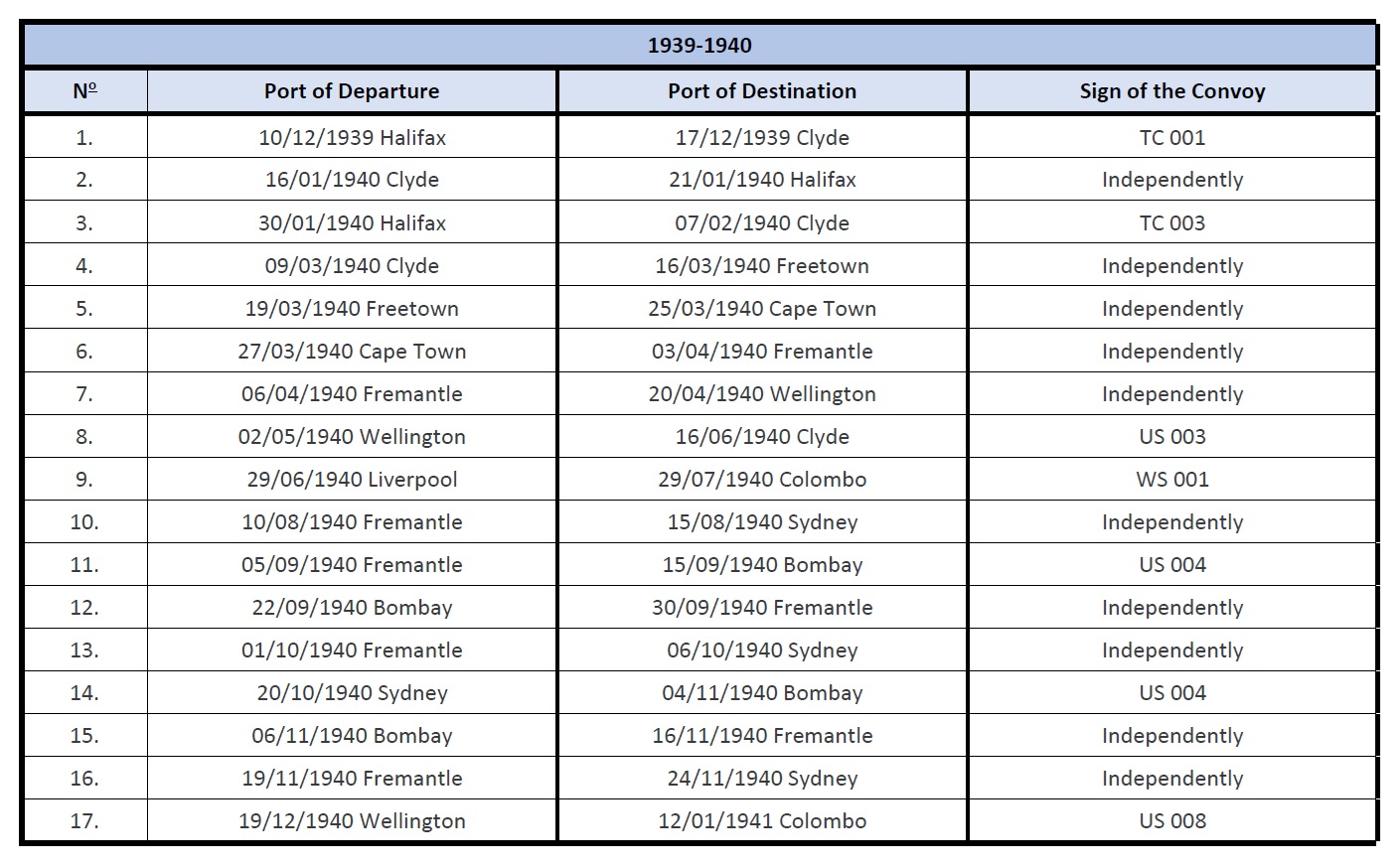

15/04/1912: The disaster of the TITANIC.